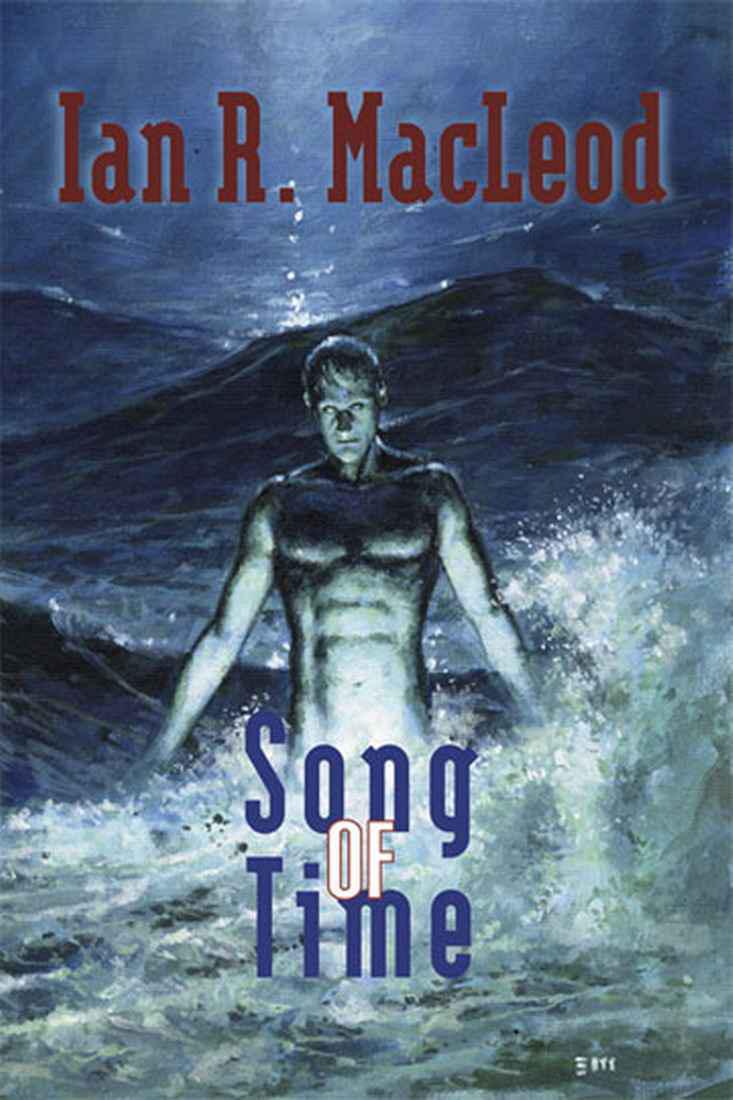

Song Of Time

Authors: Ian R. MacLeod

SONG OF TIME

by

Ian R. MacLeod

SOMETHING WHITE’S LYING ON THE SHORE as I cross the last ridge of shingle. Seagulls rise as I trudge towards it. I’d walk on if I could be sure that it was merely a salt-bleached log, but I can’t simply turn away. The ground slips and a bigger wave breaks over my knees. A hand flails, limbs unravel, bubbles glitter, and a human face stares up from the retreating sea, masked with weed.

I grab a hand, an arm. A sudden backwash almost claims us, then, in a heave, I and the body are free. I look around. Splinters of dawn light part the clouds, but there’s nothing else here along this shore but me, this man and the grey Atlantic. There are bruises, scratches, gouges, beneath the stripes of weeds which cover him, but otherwise he’s naked. And he’s obviously young, clearly male, and still alive— if barely. I struggle to turn him over and attempt to pump the water from his lungs, but already I’m exhausted. He struggles against me and blinks.

“Who are you?”

He blinks again.

“Where are you from?”

The blued lips shape to say something, then he vomits up the sea.

Arm in arm, we stagger towards the cliffs. The many steps which ascend to my house from beside the boathouse are of age-corroded concrete. I really should lay him here out of reach of the sea and hurry alone up to Morryn—I should alert the relevant authorities. Instead, his weight drags my shoulders as we climb together and the disappointed gulls swoop. His bare feet, as they stub and blunder, begin to bleed.

At last, we reach the chimneys of Morryn. We struggle up the sloped lawn, I stab my fingers at the controls on the front door, then we slump dripping into the hall. Where to put him? I have a bedroom upstairs which I reserve for the guests who never come, but I can’t face another climb, so it has to be the music room. I kick open the door, then make a final lunge towards the red divan just as the weight of his body begins to topple me.

Buffeted by weary waves of pain, I collapse on the chair beside my desk. Consciousness fades. When it returns, the figure is still sprawled across the divan. No, he’s not a ghost, for there are dribbles of seawater across the rugs, and he’s brought with him the smells of the shore. It

did

happen. His eyes are closed. A fallen hand twitches. It’s stuck with fragments of shell, and the nails are cracked and chipped. Even allowing for the damage of our journey up those steps, his feet also look sore and abraded. Is all of this just from rocks and shingle? Standing up, I cross the littered rugs to examine him more closely. His skin has mostly shed the stripes and tangles of weed. It’s blued with bruises, criss-crossed with scratches, greyed and reddened with many small abrasions, although underneath it seems softly, uniformly, goldenly, pale. His muscles are well-developed. His hair, both on his head and his groin, is drying to a darkish blonde. He could be a drowned Greek god.

“David, is that your name?”

The eyes flicker in a wet glint.

“Can you hear me…?”

A trailing leg moves. He’s looking up at me now, but the gaze is barely focused. Muscles rope in a spasm, then he falls back. When the eyes slip closed again, I sense that he’s shutting me off. In another moment, the breathing has slowed. The eyeballs flicker. He seems to be asleep…

Leaving him, I close and lean against the music room door. My senses blur. Just what

am

I doing? I’m soaked, stuck with the bits of shore and weed he’s sloughed off on our journey. I, too, wish I could sleep, escape…But I head instead for the laundry cupboard. The house implement which airs and presses my linen extends its silvery limbs as I reach to scoop up towels and blankets, but I bat it away, then struggle with arms full to get the music room door open again. Inside, the automatic piano shines its wooden sail, filled with the morning which floods through the wide bay windows. Why did I choose to put him in this of all rooms, where everything is so personal, so much a part of me? These walls lean with awards, gold disks, rare scraps of manuscript, antique concert programs, images of my husband Claude conducting the world’s great orchestras. The floor is strewn with family photos, old CDs, scraps of image, my children’s crayon drawings. My desk is a shrine piled high with the past. My Guarneri violin lies waiting in its case. All I am is here—everything that I could find, anyway. Yet now I’ve brought in this stranger…

My hands are trembling as I cover my drowned man with blankets. He certainly isn’t starved and—despite all these many small wounds—he looks almost heartbreakingly perfect. His body hasn’t been distorted or changed in the way that so many are nowadays either, and his penis is plump and jaunty despite the cold. He simply is what he is: human, young, living, male. I’d forgotten how beautiful people can be in this pure animal state. His hand no longer twitches. As I lift his head to place a towel under it, he gives a small smile.

My mind circles the obvious point. This is far from the first time bodies have been found washed up along these Cornish shores. There always have been wrecks and drownings, and the refugee ships and dirigibles of all the recent diasporas often crash or sink when they are intercepted by the guardian subs and drones. And refugees are often male and young, just as they have always been. What happens to them if they are captured alive? Sent back, I suppose, to the droughts of Africa, the sink cities of Southern Europe…

Outside the music room’s windows, the segmented sky and horizon remain empty. There are no ships, aircraft, or visible automata. Perhaps he’s nothing more than an early-morning swimmer, caught by cramp or an unexpected current? But in that case, desperate relatives would already be searching for him. And if they were, drones and flitters would also be crawling and scanning the beach. People are easy to find now, at least the ones who are fortunate enough to live in these parts. We radiate like beacons to the waymarks which help protect our boundaries. If he were a local yachtsman heading out from Fowey or Mevagissey or Penzance, or pleasure-seeker, or cliffside walker, or merely a skinny-dipping tourist caught out by this treacherous sea, he would have been rescued long before I found him.

I study his face, trying to fix the features. Trying, as well, to remember what racial stereotype we are supposed to fear in this new century. Dispossessed Americans? Maoris? But those bogeymen lie in other decades. Now, people can make themselves look like anything. They can change their colour, re-arrange their genes. I risk raising the blankets again to check that he’s breathing. He is—and everything else is still there.

Dawn has long passed. Beyond the windows lie ambered clouds, skeins of blue. Today will be cloudy-bright. It will be sunny and rainy. There will be calm and storm. Typically Cornish late summer weather, for these, my last Cornish days. My stomach rumbles. By now, I should have coaxed coffee and croissants from the implements within the glass claw of the new kitchen, and gone through my monitoring routines and taken the palliative medicines which are supposed to control my symptoms, and then started my daily practise on my violin. And then, and then—for I was determined that I would make a proper stab, a real

start

, at arranging my memories—I would begin to go over the strew of objects which covers my desk and froths from its half-jammed drawers. My head spins as I ease myself back into the chair. I’ve never been a great one for throwing things away, but it’s not like me to exist in quite this level of clutter. But what else can I do? What other choice is there?

This house, these thick granite walls, have absorbed the sighs and screams of birth and death and every other kind of memory for the best part of four hundred years. For Morryn, it really is the start of just another day. I slide open drawers. Holiday seashells, ancient CDs, dried out pens, a single earring, my first tuning fork, datasticks and gimcrack souvenirs, all slide and roll. Here’s a postcard Mum once sent me from Delhi. Tilt it at the right angle, hold it close enough to your ear, and it still activates; you can hear the murmur of traffic, smell jasmine and garbage, taste the dust of that lost city. Here’s the red plastic shoe of a Barbie doll. Here’s a note from Claude, scrawled in that big, elegant handwriting, which probably once came with a gift. And floating above this desk is the screen of the thing which I still think of as a computer, although it has no physical frame. Activate it, and I could wade even deeper into memory: access old school reports which Dad once hand-scanned into a computer in one of his attempts at orderliness—

Roseanna

(the teachers often misspelt my name)

is a very lively child.

When

she settles to a task, however…—

half-corrupted e-mails, videos of birthday parties, multisense recordings, and a near endless variety of my and Claude’s performances. It’s all there, waiting. But where to start? This is my life, yet it’s far too much for me to cope with.

I’m dying. The thought still comes as a cold shock. I feel ridiculous, disappointed and—yes—angry. After all, I’m barely a hundred, and I certainly hadn’t planned that my recent concerts would be my last. I put my surprising weariness down to a punishing schedule—for touring and performing is always hard work. In the space of just two months, I gave twenty-one chamber recitals and fifteen concert performances across the globe. I watched the earth vanish and the stars appear through the windows of a dozen shuttles. People, I was gratified to discover, still wanted to hear Roushana Maitland’s fabulous tone, which was once famously described as being as clear as the noonday sun glinting on an iceberg. I played my violin, and the music remained immortal, and so, I thought, was I. I saved the tremors, the dizzy spells, the fuzzy vision, the inexplicable bouts of sobbing, for hotel rooms, then dressed and went out to dine in the world’s best restaurants with new and rediscovered acquaintances, both virtual and real. Once, a wineglass fell. Sometimes, I forgot names. In Prague, I was unable to find my way back to my dressing room from the stage, but all these things are hardly the sole prerogative of the elderly. That was what I truly believed.

There was New Jakarta. There was Bangalore—and a forced over-night stay and listening to the hum of some environmental device as toxic rain battered my hotel window. Then came Sydney, and that last triumphant encore, and a late meal and an even later party. When the door to my hotel suite finally kissed itself shut, I was no longer sure whether I felt happy or sad that my tour was at an end. Basically, I was nostalgically drunk, and my ablutions before I climbed onto the bed and willed it and the world to stop rotating were perfunctory. No surprise, then, that it should be almost noon by the time I awakened, nor that I should have a blazing thirst. But my bed felt clammy. At first, the sensation wasn’t unpleasant. In fact, I smiled through my headache as I remembered the lost times my daughter Maria had climbed stealthily into my bed and I’d been awoken by this same wetness and smell. Only then did I realise.

Back here, back in Fowey, I made a discreet appointment. I told no one, least of all my children Edward and Maria—and who else is there left to tell? The machines at the clinic sniffed and tutted at me for being the living, breathing anachronism I’ve wilfully become. And if some special implant or enhancement really would sort out the problems with my sight and this bladder complaint, then, well, I supposed I’d grudgingly submit…But I knew something was more seriously amiss when a real, human, doctor entered the bright room. His face was professionally grave as he asked me to sit down.

There are other clinics. Not those which deal with the merely living, but which cater for the nearly dead. In my hurried researches, I found that they are often housed in old buildings which this new century has emptied of their intended purpose. Banks. Churches—the un-firebombed ones, anyway. Once-modern government offices which have escaped the concrete virus. Museums as well. But they all seem so

solid

now. They make a statement even before you enter them, and that statement echoes as you click along refurbished halls. It shines in the brass plaques which catch your face as you glance into them, amazed to find yourself finally here.