Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect (2 page)

Read Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect Online

Authors: Matthew D. Lieberman

Tags: #Psychology, #Social Psychology, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience, #Neuropsychology

BOOK: Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect

6.44Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

That night, nearly 70 million Americans watched the debate and came away convinced that the Gipper still had his mojo.

Any fears people had that President Reagan had slipped were assuaged.

But how we as a nation reached this conclusion on that night is surprising.

Reagan himself didn’t change our minds about him.

It took a few hundred people in the audience to change our minds.

It was their laughter coming over the airwaves that moved the needle on how we viewed Reagan.

Social psychologist Steve Fein asked

people who had not seen the debate to watch a recording of it in one of two ways.

Some individuals saw clips of the debate and the audience’s reaction as it was played on live television, while others saw the debate without being able to hear the audience’s reactions.

In both cases, viewers heard the president deliver the same lines.

Viewers who heard the audience laughter rated Reagan as having outperformed Mondale.

However, those who did not hear the laughing responded quite differently; these viewers indicated a decisive victory for Vice President Mondale.

In other words, we didn’t think Reagan was funny because Reagan was funny.

We thought Reagan was funny because

a small group of strangers in the audience thought Reagan was funny.

We were influenced by innocuous social cues.

Imagine watching the debate yourself

(or maybe you did watch it).

Would you think audience laughter could influence your evaluation of the candidates?

Would you be influenced by those graphs that CNN shows at the bottom of the screen during today’s debates to indicate how a handful of people are responding to the candidates, moment by moment?

Would it sway your vote?

Most of us, I suspect, would say no.

The notion that our decision about who should be the president of our nation could be altered by the responses of a few people in the audience violates our theory of human nature, our sense of “who we are.”

We like to think of ourselves as independent-minded and immune to this sort of influence.

Yet we would be wrong.

Every day others influence us in countless ways that we do not recognize or appreciate.

If this is true, why would our brains be built to be unwittingly influenced by people we don’t even know?

Before judging the gullibility of our gray matter so harshly for using audience reactions to make sense of Reagan, let’s take a moment to appreciate just how difficult it is to read other people’s minds, to discern their character from the things they say and do.

Thoughts, feelings, and personalities are invisible entities that can only be inferred, never seen.

Assessing someone else’s state of mind can be a herculean undertaking.

Was Reagan still Reagan?

Or had his mental faculties diminished?

How could we know the difference without extensive neurological examinations?

We all engage in this kind of mindreading of others every day; and it is so challenging that evolution gave us dedicated neural circuitry to do it.

While we tend to think it is our capacity

for abstract reasoning that is responsible for

Homo sapiens’

dominating the planet, there is increasing evidence that our dominance as a species may be attributable to our ability to think socially.

The greatest ideas almost always require teamwork to bring them to fruition; social reasoning is what allows us to build and maintain the social

relationships and infrastructure needed for teams to thrive.

That the brain has a network devoted to this kind of

mindreading

of others is the second of the three major brain adaptations I will discuss in this book.

The surprising thing is that even though social reasoning feels like other kinds of reasoning, the neural systems that handle social and nonsocial reasoning are quite distinct, and literally operate at odds with each other much of the time.

In many situations, the more you turn on the brain network

for nonsocial reasoning, the more you

turn off

the brain network for social reasoning.

This antagonism between social and nonsocial thinking is really important because the more someone is focused on a problem, the more that person might be likely to alienate others around him or her who could help solve the problem.

Effective nonsocial problem solving may interfere with the neural circuitry that promotes effective thinking about the group’s needs.

The presence of a dedicated system for social reasoning in our brains still doesn’t explain why most people watching the presidential debate were so affected by the responses of the audience.

In this situation, the social reasoning system appears to have failed, resulting in distorted perceptions of the debate.

Some part of our minds mistook anonymous audience laughter as a valid indicator of Reagan’s mental vigor.

Why would we substitute the judgment of others for our own?

This was no momentary lapse.

The world is filled with such laugh tracks and other contextual cues because our brains are designed to be influenced by others.

Our brains are built to ensure that we will come to hold the beliefs and values of those around us.

In Eastern cultures, it is generally accepted that only by being sensitive to what others are thinking and doing can we successfully

harmonize

with one another so that we may achieve more together than we can as individuals.

We might think that our beliefs and values are core parts of our identity, part of what makes us

us

.

But, as I’ll show, these beliefs and values are often smuggled into our minds without our realizing it.

In my research, I have found that the neural basis for our personal beliefs overlaps significantly with one of the regions of the brain primarily responsible for allowing other people’s beliefs to influence our own.

The self is more of a superhighway for social influence than it is the impenetrable private fortress we believe it to be.

Our socially malleable sense of self, which often leads us to help others more than ourselves, is the third major adaptation I’ll be discussing.

Social Networks for Social Networks

Most accounts of human nature ignore our sociality altogether.

Ask people what makes us special and they will rattle off tried-and-true answers like “language,” “reason,” and “opposable thumbs.”

Yet the history of human sociality can be traced back at least as far as the first mammals more than 250 million years ago, when dinosaurs first roamed the planet.

Our sociality is woven into a series of bets that evolution has laid down again and again throughout mammalian history.

These bets come in the form of adaptations that are selected because they promote survival and reproduction.

These adaptations intensify the bonds we feel with those around us and increase our capacity to predict what is going on in the minds of others so that we can better coordinate and cooperate with them.

The pain of social loss and the ways that an audience’s laughter can influence us are no accidents.

To the extent that we can characterize evolution as designing our modern brains, this is what our brains were wired for: reaching out to and interacting with others.

These are design features, not flaws.

These social adaptations are central to making us the most successful species on earth.

Yet these social adaptations also keep us a mystery to ourselves.

We have a massive blind spot for our own social wiring.

We have a theory of “who we are,” and this theory is wrong.

The goal of this book is to get clear about “who we are” as social creatures and to

reveal how a more accurate understanding of our social nature can improve our lives and our society.

Because real insight into our social nature has gained momentum only in the last few decades, there are tremendous inefficiencies in how institutions and organizations operate.

Societal institutions are founded, implicitly or explicitly, on a worldview of how humans function.

These are theories regarding the gears and levers of our nature that institutions try to operate on in order to strengthen society.

Our schools, companies, sports teams, military, government, and health care institutions cannot reach their full potential while working from erroneous theories that characterize our social nature incorrectly.

The same holds true for teams within an organization.

How should team leaders think about the social well-being of their team members?

Does feeling socially connected make people socialize more and work less, or does it make team members work harder because they feel more responsibility for the team’s success?

Any team leader ought to know which of these claims is more likely to be true because it affects how the team should be managed.

As we will see, neuroscience research indicates that ignoring social well-being is likely to harm team performance (and even individual health) for reasons we would not have guessed.

Just as there are multiple social networks on the Internet such as Facebook and Twitter, each with its own strengths, there are also multiple social networks in our brains, sets of brain regions that work together to promote our social well-being.

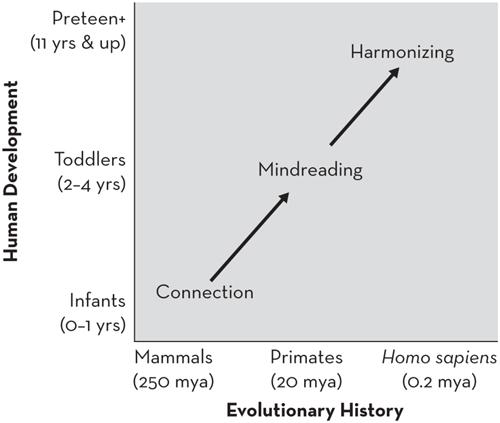

These networks each have their own strengths, and they have emerged at different points in our evolutionary history moving from vertebrates to mammals to primates to us,

Homo sapiens.

Additionally, these same evolutionary steps are recapitulated in the same order during childhood (see

Figure 1.1

).

Parts Two, Three, and Four of this book each focus on one of these social adaptations:

•

Connection:

Long before there were any primates with a neocortex, mammals split off from other vertebrates and evolved the capacity to feel social pains and pleasures, forever linking our well-being to our social connectedness.

Infants embody this deep need to stay connected, but it is present through our entire lives (Part Two:

Chapters 3

and

4

).

•

Mindreading:

Primates have developed an unparalleled ability to understand the actions and thoughts of those around them, enhancing their ability to stay connected and interact strategically.

In the toddler years, forms of social thinking develop

that outstrip those seen in the adults of any other species.

This capacity allows humans to create groups that can implement nearly any idea and to anticipate the needs and wants of those around us, keeping our groups moving smoothly (Part Three:

Chapters 5

through

7

).

Figure 1.1 Emergence of Social Adaptations Across Evolution and Human Development (mya = millions of years ago)

•

Harmonizing:

The sense of self is one of the most recent evolutionary gifts we have received.

Although the self may appear to be a mechanism for distinguishing us from others and perhaps accentuating our selfishness, the self actually operates as a powerful force for social cohesiveness.

During the preteen and teenage years, adolescents

focus on their selves and in the process become highly socialized by those around them.

Whereas

connection

is about our desire to be social,

harmonizing

refers to the neural adaptations that allow group beliefs and values to influence our own (Part Four:

Chapters 8

and

9

).

Smarter, Happier, and More Productive

After considering how each of these networks shapes the social mind, we will turn to the all-important question for any scientific discovery: so what?

How do we use what we have learned to improve the world in meaningful ways?

In what ways do these social adaptations serve as principles for organizing groups, enhancing well-being, and bringing out the best in others and ourselves?

In Part Five of the book, I will answer the

so-what

question for three domains of life.

I will examine how our social connections can be enhanced in our daily lives to increase our overall well-being in life (

Chapter 10

).

I will explore how we can make the workplace more responsive to our social wiring and how leaders can apply what we know about the social brain to improve workplace morale and productivity (

Chapter 11

).

Finally, I will consider a number of ways that we can improve education, particularly in junior high, where motivation and engagement with learning typically plummet (

Chapter 12

).

Humans are adapted to be highly social, but the organizations through which we live our lives are not adapted to us.

We are square (social) pegs being forced into round (nonsocial) holes.

Institutions often focus on IQ and income and miss out on the social factors that drive us.

In Part Five, I will suggest ways to

fix this, making us smarter, happier, and more productive.

The social brain has a lot to teach us.

A Note

I came to the brain as an outsider, starting from an interest in philosophy and then getting a PhD in social psychology.

I mention this here at the outset because I want you to understand that I appreciate what it is like to be interested in the brain but to find brain science daunting.

The brain is at the seat of who we are, so it is intrinsically fascinating and holds the keys to unlocking untold mysteries.

At the same time, the human brain is the most complicated device the universe has ever known.

The brain contains billions of neurons, and each of these is connected to many others, creating an incalculable tangle of neural traffic.

To make matters worse, we have awkward Latin names for each part of the brain (worse yet, multiple Latin names for the exact same part of the brain!).

I spent years studying neuroscience before I stopped feeling completely overwhelmed.

Throughout

Social

, I will focus on one brain region or system at a time.

I will tell you what you need to know about the region or system, but I will keep the focus on what the study of such brain regions tells us about the mind, about who we are, about our social nature.

Other books

The P.J. Stone Gates Trilogy (#1-3) by Dyllin, D.T.

The Last Days of Disco by David F. Ross

Crossing the Line by Karla Doyle

Ancient Forces Collection by Bill Myers

Scandals of an Innocent by Nicola Cornick

Burned by Sara Shepard

Rising In The East by Rob Kidd

The Dragon in the Ghetto Caper by E.L. Konigsburg

Wizard by Varley, John