Soapstone Signs (3 page)

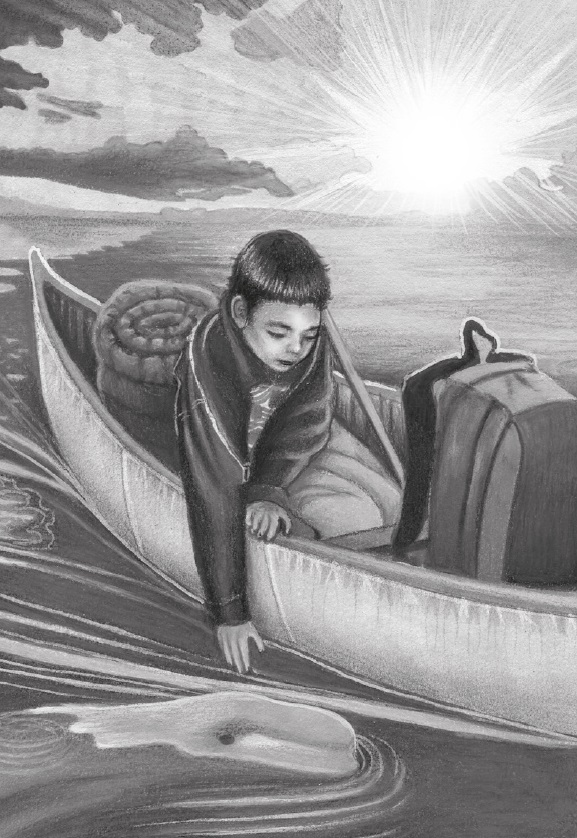

We can still hear the echoes of the belugas as they slowly move away from the canoe.

Lindy says that whales are magical because you never see them comingâthey just appear. Now I know what he means.

“Why do they come here?” I ask Mom. I want to know everything about wapamegwak.

“They like to scratch on the gravelly river bottom while they get ready to molt their old skin. They also like to eat the whitefish that are found here this time of year.”

“Is Little Wapameg a new baby?” I whisper.

“No, I have seen them together before. Mother Wapameg has raised a beautiful child.”

“Is Little Wapameg a boy or a girl?”

“What do you think?”

“I think Little Wapameg must be a boy.”

“I think maybe you are right.”

“How will Little Wapameg know when he is all grown up?”

“Little Wapameg is about the same age as you. But what takes wapamegwak one year takes us two. He will turn from gray to white and then will know it is time to swim on his own. Mother Wapameg will soon have to say goodbye.”

Mom and I stay floating there until the wapamegwak are out of sight. “We'd better go make camp,” Mom says. “We may see them again tomorrow. They will not come to the shallows of the river after the tide is high.”

“Why not?” I ask.

“Why do you think?”

I think about that for a whole lot of paddle strokes. “So they don't get stuck when the tide drops?”

“You are getting wise, my son,” Mom says. I feel proud to have figured that out.

Soon it will be twilight. We beach our canoe on a gravelly island and pull it up just beyond the high-tide mark. There is a place where fires have been before and a smooth flat spot for the tent.

Mom sets our fire with sticks and dried bark. Out beyond the sedge grass, I can see the bay opening wide and curving with the Earth. Mom says we will stay here until the tide is low and maybe we will see wapamegwak again. While we wait and watch, we will fill our baskets with berries.

I help Mom put the tent up and then pick enough fresh blueberries for the bannock. I gather enough wood to keep a small fire burning all night long and choose some long sticks for the bannock. Mom mixes berries into the batter and packs it onto the ends of the sticks. I set the pail for tea with a few wintergreen leaves for flavor.

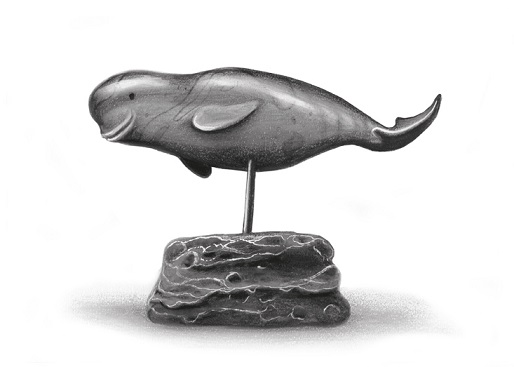

I remember the slippery feel of Little Wapameg in the cold river and the warm feeling that went through me when we looked at each other. I make a wish that we can share this river forever. I think of Lindy and then check the soapstone he gave me. I see a beluga whale inside the soapstone, waiting to be carved. Not a big white one and not a baby, but a wapameg who is growing up and getting ready to be on his own.

Powder and Bits:

A Fall Journey

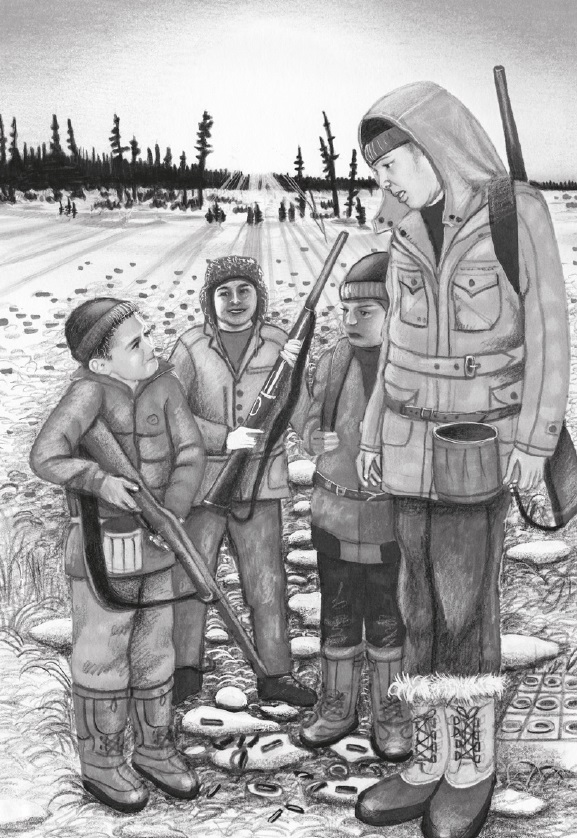

The clay skeets send white dust flying against the blue of the sky. It's like fireworks, but in the daytime. Three in a row fall, powder and bits, onto the snow and mud.

Skeets are like Frisbees made of clay. They get spun into the air and then you shoot them. It's how hunters can practice their aim. My face burns hot and cold all at once, especially the part that presses against the stock. Gunpowder smell is in the air.

The other skeet shooters are making a big deal of my shots. Chief Stan starts calling me Hat-Trick. I swallow a smile way too big for my face because I know those shots weren't just luck.

Dad is looking very proud. My brother is glaring at me, and I can tell he's jealous. He's had his gun for two seasons now, but his skeets still thump to the ground whole.

The fall goose hunt starts after one more sleep, and this time I'm big enough to go. It will be my first time using a shotgun for grown-ups, but I've practiced thousands of times in the bush with a toy one.

I am excited about being part of the fall hunt.

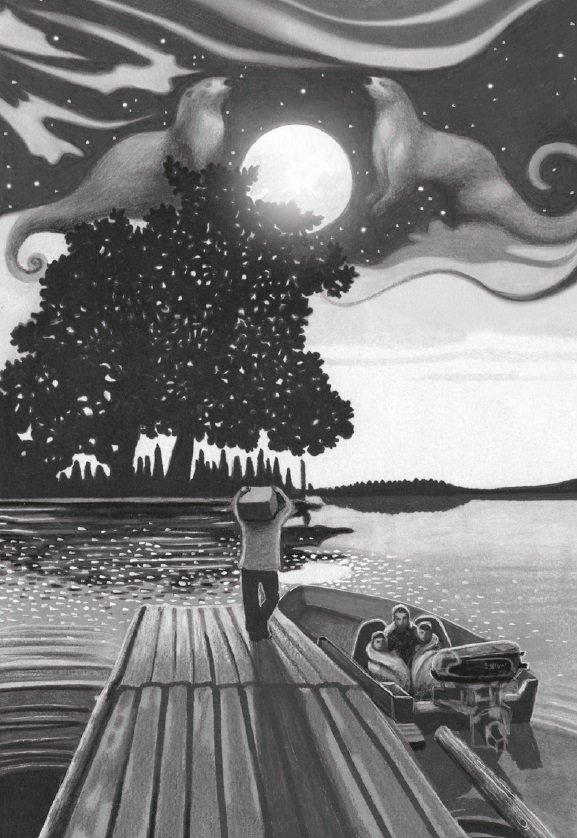

Freighter canoes float against the dark of the early-morning sky. They look black now, but they'll be green in the daylight. People move like shadows as the boats are loaded for the hunt. Stan has invited Dad, me and my brother to join him. We are hunting for the community feast that celebrates the fall harvest.

Stan is Mom's cousin. He is also chief of our band council, and we are very proud of him. He and Dad like to go hunting and fishing together. Lots of people call him Chief, but to my family, he's always just been Stan.

Dad has a big blanket wrapped around my brother and me. We sit on either side of him facing the back bench, where Stan drives the outboard. It is warm beside Dad, and he smells like home. The blanket is cozy, but I am way too excited to sleep.

Spruce, alder and tamarack trees reach from the shadows of shore. They are thin and very old. Stars twinkle through their tops. Behind us, the boat's wake swooshes white against the moonlight, then disappears into the dark purple water.

The tide is out when we arrive at the hunting grounds. The mud sucks hard against our rubber boots as we make our way to shore. I look back at our canoe and know that it will be safe. Anchors are set a special way because of the tides. Our freighter canoe will be bobbing by the grassy shore when we return.

Onshore, there are some fresh patches of snow but mostly sedge grass and hard-packed dirt. Rocks form circles where campfires have been. The charcoal smell hangs in the air when we walk by. The trail to our hunting blind is completely hidden from view, but Stan has walked it many times. He goes right to it.

Dad tells my brother and me to watch the trail. He says we might see footprints from our grandfather's grandfathers. I do not see them, but somehow I can feel them. We walk from the boats to the blind, which is way in on the marshy flatlands. A gentle hand rests on my shoulder. I look up and Stan is smiling at me.

“Hi, Stan,” I say.

Stan has a way of being silent.

“What if the geese don't come this morning?” I ask him.

“Then we go to plan B.”

“What's plan B?”

“Kentucky Fried Chicken.”

“Okay, Stan.” We both start to laugh.

He slaps me on the back like I've seen him do to Dad. When I look back down to my shotgun, I feel taller.

The blind is like a little tent made of tree branches and covered in dried grasses. Built to hide hunters from the geese, it is open at the top for shooting. All four of us fit inside, but just barely. Decoy geese made of tamarack are set up in front of the blind. One of the hunters will make noises like a goose. Real geese are tricked by the decoys into flying down to have some food.

Time passes in a special way when you are hunting. No one speaks and we hardly move. We all just sit and watch the sky turn from purple to light blue. Stan gives the signal and then shoulders his gun. We have agreed that he will shoot first.

Dad's call sounds just like a snow goose. It was the birds that brought him here, but Mom who made him want to stay. At least, that's what he tells almost every guest who comes to our lodge. He doesn't get to shoot, because hunting season for white folks starts later in the fall. White folks also have to be sixteen to start hunting, so Dad says the Cree side of me better do the hunting for a few years.