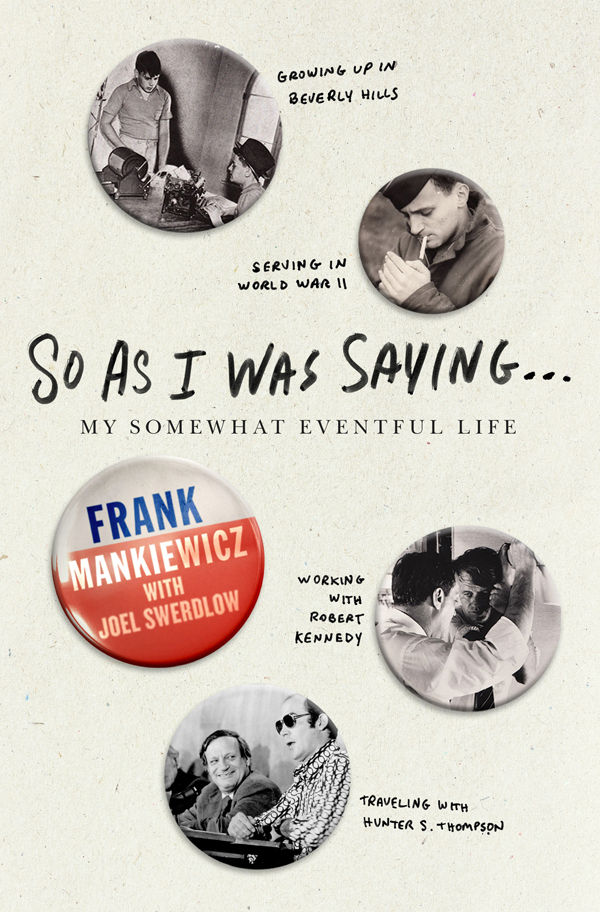

So As I Was Saying . . .: My Somewhat Eventful Life

Read So As I Was Saying . . .: My Somewhat Eventful Life Online

Authors: Frank Mankiewicz,Joel L. Swerdlow

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on Frank Mankiewicz, click

here

.

For email updates on Joel L. Swerdlow, Ph.D., click

here

.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

For my wife, Patricia O’Brien (a.k.a. Kate Alcott), the love of my life for twenty-eight years or so, who for all those years nudged me to start, and finish, this book

—Frank Mankiewicz

For my students, graduate and undergraduate—with hopes that they find in Frank’s life guidance and inspiration as their turn to shape the world arrives

—Joel L. Swerdlow

I don’t know when or by whom the portrait of my grandfather for whom I was named was created. He was a good American and spoke good English, but his aspect—at least in the portrait—was fierce and pure German. He glowered; the bald head, the firm and slightly turned-down mouth, and the bushy mustache yielded no hint of humor. It was large, well painted, and handsomely framed when I first saw it in the home of my uncle Joe Mankiewicz. He wanted me to have it, either as part of his estate or, better yet, right now. Joe hated that picture, even though his feelings about his father were mixed, at best. I, to be sure, even though I was named for the old guy, wanted no part of it, and the portrait somehow passed through Joe’s estate some years later to my brother, Don, who promptly moved it to his son, John, who soon persuaded my younger son, Ben, to accept it. There, for the moment, in Ben’s living room it hangs, and Ben, with no memory of his great-grandfather, accepts it, I hope, as a work of art.

The eponymous

Frank Mankiewicz

was an immigrant who went from the coal mines of Pennsylvania to a distinguished intellectual career as a professor of German literature. His older son (my father), acclaimed as a wit,

New Yorker

critic, and playwright, wrote the story and screenplay of what remains the most awarded and acclaimed motion picture of all time; another son, my uncle, won four Academy Awards, two as a writer and two as a director. My brother authored a prizewinning novel, created numerous super-popular television programs, and wrote a screenplay that received an Academy Award nomination. His son now writes and produces television programs, including a much-binge-watched hit on Netflix, and my two sons live in Los Angeles and have acclaimed careers, one as senior correspondent for

Dateline NBC,

a highly rated television network newsmagazine, and the other as the weekend host for Turner Classic Movies, a widely admired, internationally distributed cable channel.

I’ve always thought of that portrait as a pretty good symbol of the family. Nothing permanent, always looking toward the next act. My father, to give the best example, never demonstrated much emotion in our relationship but was always interested in what I was reading, writing, and learning. And yet one of the most emotional moments of my life came when I was aboard a troopship returning from combat in Europe, and our vessel was joined by a tugboat as we sailed into New York Harbor; from my position on the rail of our Liberty ship, I spotted a man with a gray fedora on the deck of the tug looking up at us and waving the hat. It was my father, who’d obtained the arrival time and docking information from pals in the shipping section of

The New York Times

and had somehow wangled his way on board the tug. Such emotions were always present. My father hated the movies, even though they made him rich at a young age, and passed that hatred on to me, in that I never considered writing for Hollywood; instead, I went to Washington, D.C., which offers its own form of theater.

For the past twenty-eight years or so, I’ve been blessed with four loving, and loved, daughters (to me they’re daughters, although technically I’m supposed to call them stepdaughters) and nine loving, and loved, grandchildren (six girls, three boys), the gift of my marriage to Patricia O’Brien, except for the latest granddaughter, Josie, the daughter of Ben and his wife, Lee. The daughters—Marianna, Margaret, Maureen, and Monica—and the grandchildren—Charlotte, Brendan, Sean, Sophie, Anna, Erin, Nathaniel, Elizabeth, and Josie—continue to fill our lives with pride and with joy.

So, in our family’s next generations, the portrait will undoubtedly have its first female owner. Other welcome changes will occur. But long after we “Franks” are forgotten, the bushy mustache and Germanic gaze will endure, as will whatever “Mankiewicz” has come to mean. My bet: There will be a good story. And lots of laughs.

—

Frank Mankiewicz

Washington, D.C. August 2014

“If Your Last Name Is Mankiewicz”

by Ben Mankiewicz

Writing about my father should be easy. But it isn’t. Writing is supposed to be a breeze if your last name is Mankiewicz. We have a long history of being clever. My grandfather Herman Mankiewicz wrote

Citizen Kane,

for crying out loud. My great-uncle Joe Mankiewicz wrote

All About Eve

. My uncle Don is Oscar-nominated for the screenplay

I Want to Live!

His son, my cousin John, is a successful writer on television, currently working on

House of Cards

for Netflix. Another cousin, Tom, practically invented the term “script doctor,” co-writing

Superman

and

Superman II,

as well as writing three James Bond movies. My brother, Josh, is regarded as one of the best writers and interviewers in television journalism; he’s been a correspondent for

Dateline NBC

for nineteen years.

And then there’s my father. If my dad had stayed in Hollywood, I have little doubt he’d be considered one of the great screenwriters of his generation. But instead, he moved back east and entered politics, where he wrote speeches and helped craft the messages of Robert Kennedy and George McGovern, two men I idolize.

I think the difficulty in writing about Dad comes from reconciling the two

Frank Mankiewicz

es. First, there’s the public one, the one with the epic quality to him. That’s the man who fought in World War II, proudly urinating for his country during the Battle of the Bulge, peeing on the frigid tires of his jeep to melt the ice. I fear I can’t do that man justice; after all, how many fathers have led the Peace Corps in Latin America and killed Nazis in Europe? It’s a short list.

Then there’s the dad I lived with at home, the father who went to 95 percent of my high school basketball games, taught me to follow politics, read the paper every day, and start a serious love affair with baseball, and saddled me with a moderately compulsive passion for sports gambling. That guy wasn’t epic. But he was present—which is better.

Often, as you might imagine, those two persons collided. Let me tell you a story that took place often, on nearly any Saturday in the mid- to late 1970s, when I was between seven and thirteen years old.

Dad and I did the grocery shopping on most Saturdays. We lived in Washington, D.C., but went to a market out on Connecticut Avenue in Chevy Chase, Maryland. It was big. And freezing. We actually called it “the cold market.” I loved spending time with my dad, but I didn’t like those Saturday mornings. I was a skinny kid, sensitive about my slender arms (I had a short-lived junior high nickname: Wire-Arms Willie. No clue where the “Willie” came from). I felt cold and weak in that market, while Dad always seemed fiercely strong. He loved the cold. The air-conditioning in our house was permanently set to arctic.

While I’d be enduring my unmanly shivering, week after week, Dad would be approached by a total stranger who’d stop us in the market and say something along the lines of “Mr. Mankiewicz, you don’t know me, but I just wanted to thank you.” Then this person would indicate he’d worked for Dad either in the Peace Corps, or in the Kennedy campaign, or for George McGovern, or later at NPR.

Once back home, my “big shot” dad would inevitably and inadvertently remind me that he was a regular guy. His level of frustration at not having a pen next to the phone to take notes was legendary in our house. “Why aren’t there any goddamn pens next to the phone?” he’d bellow before glancing down and seeing a pen or two obscured by the newspaper or book he’d left there. “Oh, never mind.” In the recorded history of time, nobody ever lost and regained his temper more quickly than

Frank Mankiewicz

.

Dad also tried his hand—with memorable awkwardness—at post-sexual-revolution parenting. When I was no more than thirteen, driving in our neighborhood, Dad downshifted as we headed down the hill away from our house. “You’ll enjoy driving,” he said. “But remember, the car is not an extension of your penis.”

I want to have a son just to impart that random piece of advice.

I was an incredibly shy kid, not speaking in class until eighth grade, so I was easily intimidated by a father leading such a public life. Eventually, though, I came out of my shell late in high school, growing comfortable that I could fall short of my father’s greatness yet still lead a happy and successful life. But then, after my junior year at college, I took a trip to Los Angeles. At a party, I was introduced to the host, who heard my name, looked me over, gave me a little courtesy bow, and said, “Welcome, Hollywood royalty.”

Growing up in D.C., I of course knew of the Mankiewicz family’s Hollywood accomplishments, but I was my father’s son first and foremost. To me, politics was the family business, not movies. But suddenly, three thousand miles from home, I was reminded of an additional weight: Not only was I Frank’s son, but I was also Herman’s grandson; Joe’s great-nephew.

Don’t get me wrong. I wouldn’t trade the legacy of my last name for anything, but being a Mankiewicz carries a heavy expectation, subtle but undeniable. And ultimately, inescapable. The night I started writing this, the television show

Jeopardy!

featured the category “Mankiewicz in the Movies.” I even gave one of the clues (we’d shot it months earlier at Turner Classic Movies). Seeing our name on-screen in that context was a surprising thrill. Winning an Oscar for writing

Citizen Kane

is nice, but having an entire

Jeopardy!

category to ourselves? That’s exhilarating. Herman Mankiewicz—great as he was—was never trending on Twitter.