Sleight (32 page)

Authors: Jennifer Sommersby

“What’s your poison, sweet thing?”

“I dunno. I’ve only got, like, $17. Whatever you can get that’s cheap. Whiskey, maybe. Keep the change.”

“You finish washing the side window. Look busy. I’l be right back.” He winked at me as I handed him the money.

I took the squeegee and gave the driver’s side window a half-hearted swipe with the already dirtied sponge. The guy was fast. I’d barely wiped the last of the soap off when he reappeared beside me.

“Thanks.” I took the plastic bottle and shoved it in the waistband of my pants, puling my coat over it to conceal the bulge.

“You’re not driving, right?”

“You see a car?” I gestured at the lot behind me.

He chuckled. “Smartass, huh?” extended his arm to hand me the change.

“Keep it.”

“Be safe, kid.” He stuffed the remaining dolars into his wel-worn Levis.

I chuckled under my breath. “Sure thing.”

At the edge of the gas station property, I surveyed the area to find a place to go hide. I could backtrack into the woods behind the school, but that was too close for comfort. I knew kids snuck out there at lunchtime to make out and smoke dope, and the last thing I wanted was an audience. A dirty shade was digging around in a dumpster along the side of the building. He snarled, one of his eyes missing, the back of his skul flattened. When he stood upright, a tire track stretched across what was left of his torso.

I can’t see you. Go away.

I headed north along the sidewalk, the bottle sticking to the dampness of my skin. Once I’d rounded a corner, I puled it from my waistband and shoved it into the pocket of my jacket. The sky was black except for a single break in the clouds. The sun poured through, painting a rainbow in the mist. A hundred yards ahead, I saw the gravel driveway for a park, the brown wooden sign announcing its presence tucked along the outskirts of Eaglefern.

My head was thick, the weight of this new reality pinging the sides of my skul with a force equal to that of the thunder knocking around in the sky. My cel phone buzzed in my pocket, but I ignored it. There was no one I wanted to talk to. It would be Henry or Ted, and I’d left them fighting against my escape in the nurse’s office. I didn’t want to hear if Marlene puled through the surgery because I knew the likelihood was, she wouldn’t.

“Leave me alone,” I said to no one.

A covered area in the middle of the park was nicely hidden from view of the road. I scraped my feet through the gravel, grime coating the top of my shoes, until I came to a picnic table, green with moss from the long winter months. The canopy would keep the rain from soaking me any longer, though the tal trees surrounding the picnic and playground areas were sure beacons for lightning strikes. I didn’t care. If I’d had the energy, I would’ve climbed one of those trees to the very top and tempted Zeus to strike me down.

Give it your best shot, I’d scream.

Instead, I broke the seal on the whiskey and took a long, painful gulp. It seared my taste buds and burned like hel as it slid down my throat. I had to breathe through it to keep from gagging, and the shudder from that first swalow made my head spin. I alternated between hits of Coke and whiskey, chasing the sweet with the vile.

My cel rang and rang, muffled in the fabric of my pockets. I leaned back, puled it out, and turned it off.

I polished off the Coke before the whiskey was emptied, but my tolerance to the taste, to the burn, had improved. The thunder had stopped, the sky dotted with the leftovers of angry clouds. Sun broke through in wider swaths and exposed huge patches of blue, inviting birds from their hiding places. Chirps and whistles decorated the silence of the park, hinting that spring was just around the corner, and with it the chance for new beginnings and fresh growth.

It was usualy my favorite time of year, everything beautiful and new and alive, like a deep breath in after a long time asleep.

But if Marlene died, whatever optimism I had left would die with her. Overcome with grief, I cried in rib-crushing sobs. I wanted to walow in my agony, revisit the individual horrors of the last week, as if stopping along a road to take in the dead flowers, one shriveled, decaying blossom at a time. I couldn’t make sense out of the senseless of it al. It was too much.

I cried for everything I’d lost, and for the bleakness of a future that held only the promise of additional loss. I cried for my mom, for Alicia, for Marlene, for Ted and Irwin, and most of al, for Henry, for the future we’d never know together. I cried until my reservoir of tears had been drained and abandoned to bake and crack under a cruel, hot sun. I was helpless, forsaken, empty.

The effects of the alcohol were swift and dizzying, but I welcomed the fuzz. It quieted the world, duled the excruciating pain scratching behind my eyes, in my chest, in my gut. I stretched out across the table’s surface and wiped my snotty nose on the remnants of tissue puled from my pocket. My eyes were so tired from crying, the muscles in my body sapped of energy. I was surprised that no one had folowed me when I bolted from the nurse’s room. It was unlikely that Ted could’ve kept pace with me, but I thought Henry would at least chase me out of the school. I was glad he hadn’t.

The whiskey spun the world like an out-of-control top. Ground and sky flip-flopped, and the trees mushed into a haze of green and brown. Bird screeches rattled my eardrums and pecked at my grip on reality. I was no longer capable of focusing my eyes on any one thing. Sleep. I needed to sleep.

A soft hand on my cheek puled me from the darkness of a forgettable dream. It was stil daylight, and the earlier storm had given way to a muggy warmth, the air close and moist.

“Gemma,” the voice said. I peeled my eyes open and squinted from the glare of the sun. The face standing over me was silhouetted by the brightness of the day. I was looking into a vision, light spiling around the person’s head like a halo.

The stranger helped me into a sitting position on the table, his arm under my shoulders. I wasn’t afraid, instead filed with a sensation of resolute calm. I’d seen him before…a shade. In the meal tent.

“Gemma, this is for you.” He puled a thin rope from under his coat and over his head. He reached toward me, stretching the rope until it hung around my neck. For a moment, I held my breath, wondering if he was going to strangle me with the line puled between his hands. Instead, he lifted my hair from under it, the damp curls faling down my back. He had given me a necklace.

“It wil keep away those who want to hurt you,” he said, his accent thick and exotic. “Separate it from your heart at risk of great peril.”

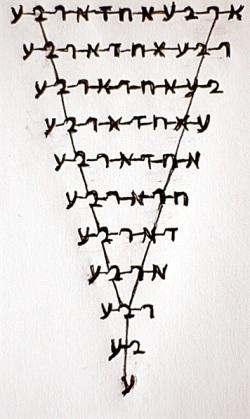

I looked down at my chest and touched the pendant that hung from the leather strand, cradling the cold, triangular-shaped amulet in the palm of my right hand. The design on the surface of the triangle was in a language I didn’t recognize, the scrol not Roman letters but definitely in the form of a pattern, diminishing from left to right:

“What is this?” I said, lifting my head to look into the man’s face.

But he was already walking away, his black trench coat disappearing into the trees.

“Keep it close.” His voice drifted into my head, the way Alicia’s had done that day in Henry’s car, the way the littlest shade had begged for my help. He then vanished from sight.

:36:

The senses deceive from time to time, and it is prudent never to trust wholly those who have deceived us even once.

—Rene Descartes

I must’ve dozed off again because my eyes were forced open when I began to throw up. Whiskey wil do that to you, especialy if you’re not a drinker to begin with and your body is ravaged with a lack of food and too much adrenaline. The morning had given me a surplus of the latter, and combining it with the alcohol zipping through my veins didn’t make me feel any better. It didn’t exorcise the demons or bring Marlene back from the brink. It just made everything worse.

Leaning over the side of the table, I retched until my gut was cleaned out. My teeth were fuzzy, my mouth dry as sand, head pounding, eyes on fire from a late afternoon sun turned onto its highest setting. A couple of cars were now in the park’s lot, though no one had approached me. Even if they had, I’d been too out of it to know any better.

I struggled to sit up, the spinning world bringing around a new bout of nausea. I realy needed to move, though, before someone did take notice of the teenager sprawled on a city park picnic table, an emptied bottle of Jack Daniels dropped onto the bench.

Moving was way harder than sitting, and I didn’t have a clear direction as to where I should go. I contemplated turning on my phone again, caling Uncle Ted for a rescue, but I wasn’t ready to face them. Not yet. I didn’t want to talk about Auntie, didn’t want to hear that she was dead, didn’t want them fawning over me,

“poor little Gemma.” Didn’t want Henry’s warm arm around me, teling me everything was going to be al right when nothing was ever going to be al right again. I shuffled toward the sidewalk and headed out of town, beyond where the sidewalk ended, away from Eaglefern’s excuse for a downtown core.

As I moved along the road, it narrowed into two lanes, nothing but a tight gravel shoulder and swampy ditch to show me the way. I stripped off my jacket and tied it around my waist, partly because I was hot, partly because it smeled like puke. The false sensation of timelessness granted space to think, even in the hazy space that was my brain, to inspect the newness of my circumstances and consider where I fit in the bigger picture.

I’d never been one to fantasize about the milestones most people count on in their lives, of love, marriage, children, the happily-ever-after. How could I, with my mother for a role model? My priority had always been on self-sufficiency, making it through one day at a time, accomplishing the smalest of tasks without ruffling feathers or bringing undesired attention upon myself. I’d learned independence at an age when most children were learning to tie their shoes or recite their phone numbers. I had long been afraid to dream of a

“normal” future because the odds were so stacked against me.

Until I’d met Henry Dmitri.

I had permitted myself the luxury of fashioning a mental image of a life with him, one where we’d spend time together doing the stupid teenager things. Movies, dinner, making out in the back seat of the car. Maybe there’d be more. Maybe we’d folow each other to university, stay together, graduate at the same time, move into a fabulous tiny apartment in the city, buy our furniture and silverware at IKEA, and adopt a cat. Then someday, maybe, we’d go to dinner in our favorite little Italian restaurant and he’d get down on one knee with the black velvet box, inside of which would be a symbol of what I meant to him. Just like in the movies.

And in the unforgiving blaze of life as it stood at that moment, I felt both anger at my momentary weakness and grief for the loss of a future I had yet to experience. I felt abandoned by the people in my life who had alowed a psycho to dictate to them how they were to manage their day-to-day affairs. If Marlene died, it would be Lucian’s fault. My father’s fault.

Because I’d run away from Ted and Irwin when they needed me most, I was a selfish coward. No amount of magical pedigree could undo that. It didn’t matter that Lucian was my father, and that Marku practicaly begged me to step in and stop his son’s deranged plans. I couldn’t be heir to anything. The pile that Ted had stepped in when he took the book from Marku and fled to America with Alicia was his problem. He was going to have to clean it up.

My left foot caught on a crack in the pavement and I fel, hard onto my knees and outstretched arms. In another example of my stunning grace, I landed squarely on a sharp rock that tore my pant leg open. The fibers of the denim quickly soaked with blood from the new wound. It stung like hel, but the tears that came had little to do with pain and everything to do with how pissed off I was at the universe.

I sat clutching my bent leg for a few moments, rocking back and forth in the gravel, smacking at the mosquitoes that added insult to my latest injury. A few cars passed but, of course, no one bothered to stop. And why would they? It made me even angrier that the world had come to a place where people had lost al common decency, that not a single person stopped to help a crying, bleeding girl on the side of the road.

Another car flew past and I didn’t bother to look up, not until I heard the brakes squeak and the car’s tires peel against the pavement as the car turned around. It puled up behind me, and the driver was out in a quick bound, a young man’s voice folowed by the pound of his footprints on the road.

“Gemma? Jesus, are you okay?”

Bradley Higgins kneeled down next to me, looking at the rip in my pants and the puffy state of my face.

“Hey,” I said.

“What the hel are you doing out here?”

“I went for a walk.”

“Some walk. Shit, you’re bleeding.”

I nodded. “Yeah, looks that way.”

He leaned in and sniffed. “And you stink.”

“Wow, thanks.”

“Been drinking?” I didn’t answer him. “Whatever. Come on, let me help you up. I’l give you a ride home.”

I wanted to ask him why he wasn’t in class, but judging by the sun’s position in the sky, I guessed that school was over. I’d spent the day passed out on a picnic bench instead of zoning out in the classroom.