Slayer 66 2/3: The Jeff & Dave Years. A Metal Band Biography. (12 page)

Read Slayer 66 2/3: The Jeff & Dave Years. A Metal Band Biography. Online

Authors: D.X. Ferris

Rare foto (sic) collage from the Stone, San Francisco, 1984. By Harald Oimoen.

King on Hanneman: “We were just like the same person.” By Harald Oimoen.

King and two dark towers of amps. Photo by Harald Oimoen.

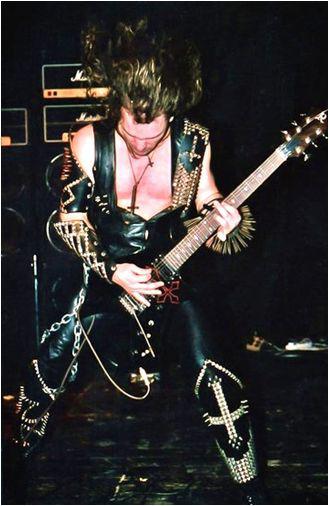

Shining steel, black leather: King dressed for battle at the

Kabuki Theatre, San Francisco. 1985. Photo by Harald Oimoen.

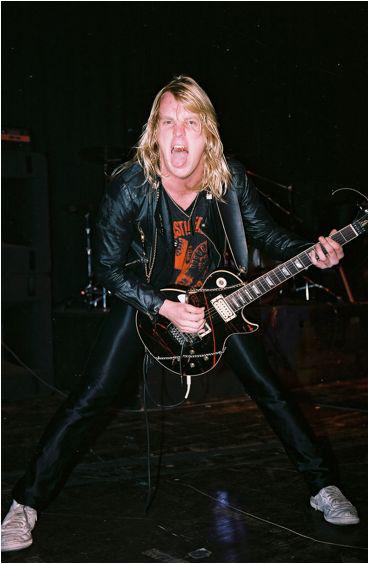

Hanneman. Representing New York Hardcore on the West Coast: Note the Agnostic Front T-shirt. Hanneman, who once shaved his head, was the first of the frontline to outgrow the hell-bent-for-leather look. Photo by Harald Oimoen.

At the Kabuki, brothers in arms. 1985. King and Kirk Hammett, whom Metallica poached from Exodus, leaving future Slayer guitarist Gary Holt to hold the frontline in the oldest of the Significant Seven thrash bands. King on Exodus: “I think Metallica took the wrong dude. Gary Holt’s bad-ass. And that’s not to say Kirk Hammett isn’t.” Photo by Harald Oimoen.

Metal fans like Hanneman had stumbled across hardcore bands like TSOL at parties, bought their records, and followed them to punk shows, where they discovered full-scale slamdancing.

“In the beginning, Dave and Jeff were into punk, and I hated it,” King told

Guitar World

in 1995. “I think that’s what made Slayer what it was — they were listening to punk, and I was listening to Judas Priest. The reason I didn’t like punk was that I was really into singers like [Judas Priest’s] Rob Halford, and I couldn’t get into punk vocals…. Now I’m the punk guy in the band.”

11-2

Slamming and stagediving were old news to punks, but punk energy was still new to most metalheads — most of whom, at best, still regarded hardcore kids as junkie cousins, distant members of the family at best, certainly not brothers in the underground scene. But moshing stirred the melting pot.

Whether inspired by punks or provoked by Lombardo, pioneering crossover fans brought the slam to Slayer. At metal concerts, the floor in front of the stage had traditionally been filled with furiously banging heads, hair waving back and forth, fists pumping in the air. With Lombardo pushing 200 beats per minute, Slayer was so exciting that banging your head wasn’t enough. In Southern California, Slayer is the band that fully cracked the crowds open.

“I can tell you the first song where a stage dive and a pit broke out,” recalled Hoglan. “That was during ‘Necrophiliac,’ I think they were playing somewhere in South Gate, or maybe Pomona. This would have been ’84. Tom was like, ‘This is the first time we’ve ever played this song. It’s called ‘Necrophiliac.’ And he had the very same rap about the maggots crunching in the teeth.

“A dude jumps on stage, dives off, starts a little pit, and the crowd didn’t know what to do,” says Hoglan. “The crowd was very shocked, like ‘What is this guy doing?’ And people wanted to beat him up for bumping into them. And I’d been to every single Slayer show and all the Dark Angel shows and all the Hirax shows, and Abattoir, and Bloodlust, and nobody had busted out with a pit before.”

(As far as I could discern, “Necrophliac” made its live debut at Madame Wong’s in L.A., March 2, 1984; Hoglan passed on follow-up requests to identify the exact date. He stages spoken-word/drum clinic sessions called The Gene Hoglan Experience, in which he answers questions from the audience. If you see him, ask.)

Between January and June 1984, Slayer had played around 30 shows all over California. Pits spread through the Golden State like wildfire. In those months, the stage-diving, elbow-throwing, circle-pitting crowds became a permanent part of the concertgoing experience. Worlds collided and combined later in the year, when Slayer played shows with Suicidal Tendencies.

Technically, Suicidal was a hardcore band, but the group was the center of a self-contained scene that the collective Southern California punk scene hated until crossover kings became undeniable. Though Slayer and Suicidal were not major influences on each other, their connections were significant.

Hanneman was best buds with Rocky George, the black Suicidal guitarist known for wearing a Pittsburgh Pirates ballcap. The jazz-influenced George coached along Hanneman’s nontraditional playing style. They were bandmates briefly.

In 1984, George joined Hanneman and Lombardo in Pap Smear, a punk side project. The group recorded a demo with Hanneman writing the songs and singing them. Slayer rerecorded two of the tunes — “Can’t Stand You” and “Ddamm” (a play on the parents group Mothers Against Drunk Drivers) — for 1996’s punk covers album,

Undisputed Attitude

. “DDAMM” is an archetypal hardcore jam about bad boys running wild, but the songs aren’t standouts in that set.

Pap Smear was still going in 1986, when Slayer joined Def Jam. Rubin, the band’s shepherd into the larger rock world, sensed some potential in the group, if only the potential for disruption. Rubin, always the student of rock history, urged Hanneman and Lombardo to break up the band because spinoff projects tend to wreck the mothership. They relented.

(Lombardo is the only member of the original unholy four with a real body of work outside the group; Araya has written acoustic material, but never released it. He cameo’d on Alice in Chains’ grunge classic

Dirt

in 1992. In 2000, he quoted “Criminally Insane” in a duet with Max Cavalera on Soulfly’s “Terrorist.” And he recorded a cover of Black Flag’s “Revenge” with the Rollins Band in 2002. King, like Metallica’s James Hetfield, has turned in a series of guest appearances over the years: He soloed on Pantera’s “Goddamn Electric,” Sum 41’s “What We’re All About,” Witchery’s “Witchkrieg,” and Rob Zombie’s “Dead Girl Superstar.” In 1987,

King and future Metallica bassist Jason Newsted made a guest appearance during a Sacred Reich set,

helping cover for a sick Phil Rind at Phoenix’s Mason Jar club. Hanneman only recorded Pap Smear demos.)

Rubin came to Slayer through a Suicidal connection.

Araya had popped up in Suicidal’s classic video “Institutionalized” in 1983, popping up at the :35 second mark, shoving singer Mike Muir mid-monologue. (King also appears in the clip; during a concert scene, a longhair with a pentagram shirt is in the front row, but George has said he appears toward the back.)

11-3

The video was co-directed by the album’s producer, Glen E. Friedman. Friedman, also a renowned photographer, would later take iconic pictures of the Beastie Boys, Fugazi, Public Enemy, and Slayer. In 1986, when producer Rubin landed in L.A. in search of Slayer, Friedman would deliver him to Tom’s garage.

For a time, Slayer and Suicidal Tendencies co-existed on the same stages. In August 1984, a four-day fest at Berkeley’s Aquatic Park featured a harder-rock day that became known as “Day in the Dirty,” with Slayer, Suicidal, Exodus, and others on the bill.

“We headlined the metal day,” recalled Muir. “There was [usually] no love for the punk thing. A lot of those people were more accepting, and they’d never heard anything [punk] that they really liked. And we took it to another level, and people saw that and accepted it for what it was.”

A month later, Suicidal opened a show Reseda Country Club in the San Fernando Valley

11-4

, and Muir introduced the headliners as “Suicidal Slayer.”

11-5

They were one of the few opening acts that ever went over well with a Slayer crowd.

“If you’ve got all that Satan stuff, you can’t really be prejudicial against Suicidal,” reflects Muir. “I think a lot of it was that we were the first ones that were playing leads, and it stuck out. And I heard a lot of people say, ‘Dude, I wasn’t into punk, but it was just cuz I didn’t like any of the stuff. But when I saw you and heard the Suicidal, I could see what you guys were doing.’”

It’s also worth contrasting the bands’ relationship with their fans. ST were part of their mob. Slayer existed on their own plane.

“Suicidal Tendencies had an entourage,” recalled De Pena. “Slayer never needed that. Slayer just had rabid fuckin’ fans. The word just spread, and everybody loved them. The people that hated them were pussies anyway, so no one cared.”

Slayer seemed to materialize for shows, whip the crowd into a hellstorm, and disappear back into the nether realms. A Slayer gig was the only place you were likely to see all four members of the band together. The band didn’t even drink at the bar before shows. Gigs were all business. And the members were never more social then they needed to be.