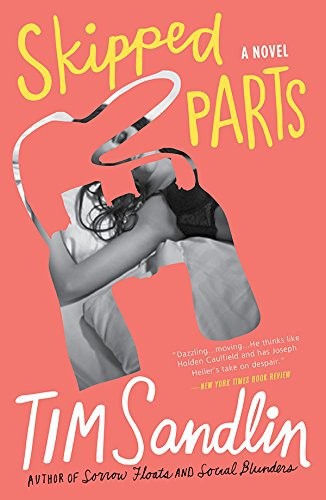

Skipped Parts: A Heartbreaking, Wild, and Raunchy Comedy

Read Skipped Parts: A Heartbreaking, Wild, and Raunchy Comedy Online

Authors: Tim Sandlin

Tags: #Fiction, #Coming of Age, #Humorous

Copyright © 1991 by Tim Sandlin

Cover and internal design © 2010 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Jessie Sayward Bright

Cover images © Luis Alvarez/Getty Images

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor in this book.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sandlin, Tim.

Skipped parts / Tim Sandlin.

p. cm.

1. Teenage boys—Fiction. 2. Divorced mothers—Fiction. 3. Mothers and sons—Fiction. 4. Teenage girls—Fiction. 5. Teenagers—Sexual behavior—Fiction. 6. Adolescence—Fiction. 7. Maturation (Psychology)—Fiction. 8. City and town life—Wyoming—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3569.A517S55 2010

813’.54—dc22

2010020944

For Carol and Kyle,

Marian, my editor and friend,

and Sally, my sister

I couldn’t live the way I do without a lot of humoring from the people of Jackson, Wyoming, especially Michael Sellett who owns the

Jackson Hole News

where I work, and the employees of Jedidiah’s Original House of Sourdough, the Valley Bookstore, and the Teton County Library who keep me fed and pointed in the right direction. None of the beauty of life in paradise would mean squat without friends like Lisa Bolton, Lisa Flood, Pam Stecki, Hannah Hinchman, Shelley Rubrecht, and Teri Krumdic. Tina Welling read the manuscript and helped immensely.

Although I never met them, Ed Abbey and John Nichols showed me there is no excuse for not living where you want to live or doing what you want to do—a good lesson to learn while you’re still young.

We were as twinned lambs that did frisk i’ the sun And bleat the one at the other. What we changed Was innocence for innocence.

—Polixenes, King of the Bohemians

The Winter’s Tale

The two grey kits,

And the grey kits’ mother

All went over

The bridge together

The bridge broke down

They all fell in

May the rats go with you

Says Tom Bolin.

—Nursery Rhyme

I remember being way out in right field and my nose hurt. Hurt like king-hell, as if my sinuses were full of chlorine. Now I know that when anyone moves from the South to Wyoming, their nose always hurts like king-hell for two weeks. Has something to do with the humidity, I guess, or the altitude.

But at the time, standing out there in right field pretending to spit in my glove so I could hide my right hand as it pinched my nostrils, I thought Lydia and I were the first Southerners ever lost in Wyoming. I also thought the nose pain meant I had leukemia and would die soon.

“Sam, Sam, can you hear me?”

Sam’s eyes fluttered in weak recognition of his grandfather’s presence.

“Sam, I’m so sorry you’re dying of leukemia, I’m sorry I shipped you and your mom out to the Wilderness when you needed to be home the most.”

Sam tried to raise his hand. It was a noble effort.

“Sam, this is your grandfather, can you forgive me before you die?”

The poor boy’s lips worked, he made the supreme effort, but no words of forgiveness would escape his mouth. Slowly, painfully, he smiled.

***

Back then I often had recurring daydreams of people being sorry when I died.

Out in right field, I was keenly aware that people were watching me. Where they watched from, I wasn’t certain, but I always know when I’m being watched. It makes my butt itch. I have a feeling this deal goes back to the second grade when Lydia told me not to scratch in public because someone was always watching. Lydia’s the kind of mother who would do that to a kid.

Since I couldn’t scratch where it itched and my nose hurt like king-hell, I stood out there in right field kind of twitching. I hunched my right shoulder up to rub my ear, then blinked my eyes hard, trying to scratch my sinuses from the inside. I raised up on my toes and tensed my butt cheeks. That didn’t help at all, made me feel more watched.

The trouble, of course, was social alienation. I’d always played baseball with gas company conduits behind third base and the Caspar Callahan Carbon Paper plant twenty yards off the first-base foul pole. Now, nothing lay behind third base, only the bare valley floor stretching forever to a line of green along a river, then another forever before the Tetons jumped up two dimensional in the background.

The openness got me. There are no treeless spots in North Carolina—unless someone’s fought like king-hell to make them that way. Here, I could see a tree up by the school and a few scraggly little willows we’d call weeds marked the home run fence behind me, but other than that—zip. Zappo. Nothing. I was lost in limbo where the unbaptized babies go when they die.

Off the first-base line was almost as bad. A bunch of rural, shrieking types played pathetic volleyball. They all had their hands over their heads like apes. I could see pit stains from thirty yards. If the wind changed, I’d be in big trouble.

The batter swung wide and missed by a foot. He was tall and gangly. One thing I had to admit about Wyoming, even in the midst of my bad attitude, the kids might be ugly but hardly any of them were fat. Maybe a girl or two, and they were more muscled broad than fat. I spit in my glove again. Somewhere along the line I’d decided spit was good for leather and not to be wasted.

The kid batter swung again and again missed by a mile.

“Sam, you’ve only been gone from Greensboro a short time, yet you’ve returned with the demeanor of a cowboy.”

Sam tipped his wide-brimmed hat. “Yup.”

“You seem so much taller and more enigmatic.”

“Yup.”

Caspar had banished us before—that’s what he did when Lydia pulled one of her classic boners. But that was to Maine or Georgia Sea Island and summertime. This was a mockery. Mars. The inside of a vacuum cleaner bag.

I heard laughter. They weren’t just watching, they were laughing at me. I chose to take the high road of the sports hero and ignore them.

The night before—our first night in hell as she called it— Lydia had told me about school. “Sam, honey bunny.” The honey-bunny stuff was a nasty habit. “Sam, honey bunny, you’re at the worst age possible to be starting a new school. You can handle it one of two ways. You can wallow in superiority, tell yourself everyone’s a stupid yahoo but you.”

“Yahoo,” I said.

“Or you can be nervous as heck that you won’t fit in and no one will like you and you can suck up like a puppy dog.”

“Neither way sounds fun,” I said.

“I advise superiority. It has always stood me well.” This conversation took place before 10:30.

“Hey, kid, throw the ball.”

I ignored them. I wasn’t sure how it had happened, but the gangly kid stood on second and there was a new batter.

“Hey, dummy.”

A ranch boy crossed the foul line, walking straight toward me. I concentrated on the new batter who was a spastic or some such. He switched sides of the plate between every pitch.

The boy came up on my left. “You deaf, kid?” He was real skinny and had bad pits on his chin. When he spit a wad of juice, I looked at his swollen cheek in amazement. I’d never seen anyone chew tobacco and this guy couldn’t have been more than thirteen, fourteen years old.

“Can I help you?”

The boy wrinkled his nose and mimicked in a high voice. “Can I help you.”

“What’s the problem?”

“Our volleyball.” The boy had about six inches of extra belt hanging off his buckle.

“Your volleyball’s the problem?”

“You’ve got it.”

I looked down at the ball at his feet. Same color as Lydia’s skin. “I’m sorry, I didn’t see it.”

“How could you not see it. It’s right there.” The boy bent down to pick up the ball. “We thought you were foreign. Can’t understand American.”

From the left side of the plate, the batter drilled a high fly down the right field line and I took off. I’d show the turkeys. Not a kid in Wyoming could make this catch. I pictured myself, at a dead run, reaching out, spearing the ball, then whirling and firing a strike to the cowboy-booted second baseman to nail the gangly base runner.

Almost worked that way.

I flew across the playground, made the jump, snared the ball, and came down with my left foot in a hole. As I started to fall, I caught myself with a straight right leg, stumbled a couple steps, pitched forward, and hung myself on the volleyball-net guy wire. Would have done permanent damage, except the force of the sprawl yanked up the stake holding down the guy wire. As it was, my head jerked back, my feet kept going, and I made a sound like

yerp

. Then I slammed to my back. I rolled into the pole which, without its guy wire, fell across my body, bringing the net down on my face.

Breathing was tough. I lay in silence, staring at the blue above. A black bird circled up near a cloud. Yellowish spots formed at the corners, swelling in front of my eyes. Turning my head carefully, I looked at my left hand. The ball lay tucked in my mitt. It had been worth it.

Way high, a face came into view. She had remarkably well-defined cheekbones, dark hair pulled back, and blue eyes. Black hair and blue eyes, like Hitler.

The eyes blinked once. She opened her pretty mouth and disgust dripped off her voice. “Smooth move, Ex-Lax.”

I found Lydia stretched out on the fake cowhide couch, more or less surrounded by magazines and Dr Pepper bottles. An ashtray overflowed onto a deck of cards on the floor.

“Mom, we can’t stay here.”

“Mutual trust and respect, Sam, always remember what our relationship is based on. You must never fling in my face the fact that I am a mother.”

“These kids are morons, Mom. Lydia. Worse than morons, they’re Nazis. I almost killed myself today and they laughed. Can you believe it?”

“Children laugh at pain. It’s what makes them children.” Lydia lit a cigarette. I don’t know what kind. She made it a policy never to smoke two packs of the same brand in a row. She inhaled deeply and blew smoke at a huge stuffed moose head on the wall. When Lydia lifted her chin and squinted her eyes, her long forehead seemed to grow even longer, and her remarkably thin lips puckered into what I took as a pout. Lydia pointed at the moose with her middle finger under the cigarette. “That goes. I won’t have the dead passing for art.”

I collapsed on the foot end of the couch and kicked off my sneakers. “When we first came in yesterday, I figured out which room was the other side of the wall, and went looking for the rest of the moose.”

Lydia watched me through the light blue smoke cloud. “Most people don’t catch self-effacement, Sam. Try something else.”

I went in the kitchen and returned with two Dr Peppers. Lydia was still staring at the moose. The house had been rented to Caspar as is from a doctor who overemphasized Hemingway, which meant every room had at least one mounted head. Two antelopes flanked the bed in my room. I’d already named them Pushmi and Pullyu after two characters—one character, actually, with two heads—in a Dr. Doolittle book. The antelope on the left had longer horns that bent toward each other. He was Pushmi. I imagined Pullyu was a female.

I opened both bottles with a church key from under the sink. “Look at those nostrils. Each one’s big as a hooker’s twat.”

Lydia reached for her pop. “That’s another matter we should speak of. This is Wyoming. Thirteen-year-old boys do not compare objects to a hooker’s twat.”

“You’d rather me laugh at pain?”

“And how do you know what a hooker’s twat looks like?”

“Jesse told me they’re like a big, black, chocolate éclair.”

Lydia glanced down at herself. “I certainly don’t look like a chocolate eclair.”

“You’re not a hooker.”

Lydia propped her feet up on a pile of old

Field & Stream

s. Cigarette in left hand, Dr Pepper in right, she looked considerably more like a bad baby-sitter than anyone’s mother. She had the toes of a child. “We must be normal here,” she said. “I’m tired of trouble. If these kids are morons, just wonder where Caspar will banish us if we mess this one.”

The thought was inconceivable. I plopped into a straight chair with elk gut or something stretched across the back. “Damn, Lydia, what did you do to hack him off so much?”

She waved her hand like brushing away flies. Lydia had the longest, thinnest fingers I had ever seen. “Nothing. I didn’t do a thing.”

“Look at it from my point of view. You told me about the Cuban guy and the dancer and the strip show on the diving board. If this one’s so horrible you can’t tell me, think what my imagination is going to imagine.”

Lydia smiled. “Oh, fuck you.”

I propped my feet up next to hers and drank from the bottle. “Normal, remember. Wyoming women don’t use that word in front of their baby boys.”

“Fuck Wyoming women too.”

I went back to the kitchen, opened the freezer, and pulled out a frozen pizza. “You know how to light the oven?”

“Are you kidding?”

The apprentices’ eyes widened in fear. “Chef Callahan,” they cried. “The hollandaise sauce is separating.”

Sam smiled mysteriously to himself and tapped his two-foot-high chef’s hat to a rakish angle. “Let’s see the problem, boys.”

The apprentices, both of whom were shorter than Chef Callahan, stepped aside as Sam peered into the stainless-steel bowl. “Boys, bring me two egg yolks, a half lemon, and a tennis racket.”

“Sam, something’s wrong with the television.”

I put the pizza back in the freezer and found a pound can of cashews and a half-full jar of pickles. Caspar’s doctor friend was big on Mexican condiments. The shelves were packed with four-alarm sauce stuff, dried peppers, and boxes of prefab taco shells, nothing you could make a meal of. Back in the living room, Lydia was sitting up, squinting at a snowy picture on the TV screen.

She slapped the side of the set. “Can you believe this, one channel, if you find this a picture.”

I set the cashews and pickles on the end table that had elk horns for legs. “Hope you don’t mind a light dinner.”

“I thought maybe PBS wouldn’t come through, but this is modern America. Everybody gets at least three stations.”

We chewed cashews and watched

My Three Sons

as Mike, Rob, and Chip pushed their dad’s busted Buick up the street. I wondered what it would be like to have brothers. Or a dad. “Maybe if we put in an antenna.”

“I doubt it. We’ve fallen off the edge of the Earth. My destruction is complete. You want the last pickle?”

I settled into my end of the couch with my knees over Lydia’s legs and

A Farewell to Arms

and the

Hardy Boys Mystery of the Haunted Swamp

on my leg. The guy in

Farewell

talked like an idiot, but the war parts were neat. Every time Frederic and Catherine started doing a Punch and Judy act—I love you, Catherine, I love you, Frederic—I switched to a half-hour of the Hardy brothers wholesomely sniffing out clues.

The red phone rang twice. Sam answered, “Yes, Mr. President.”

“Callahan, we’ve got a problem.”

“That’s what I’m here for, sir.”

“The Ruskies are filling Cuba with missiles and I just don’t know what to do.”

“Blockade them, sir.”

“That sounds awfully drastic, Callahan.”

“We must be firm, sir. The Red Menace doesn’t respect wimps.”

There was a long silence. “All right, by golly, we’ll try it. You’ve never let me down yet. Callahan, I have one other question.”

“My time is yours, sir.”

“Why don’t you let your mother and school chums know that you are the principal advisor to the President? Why let them go on believing you’re just another kid?”

“It’s my way of keeping in touch with the little people, sir.”

***

The cabin was so quiet it was noisy. The toilet ran, the refrigerator kicked on and off like a lawn mower, I opened the back door twice before figuring out the water heater knocked. By 9:30 I knew who was hiding in the swamp and what kind of wine went down in an Italian pool hall.

“Mom?”

Lydia ignored me.

“Lydia?”

“Yes, dear.”

“How can you go so long without peeing?”

“It’s a sign of the upper class.”

“You haven’t moved except to play with the TV in four hours that I know of. Why don’t you go to the bathroom like other people?”

Lydia lit another cigarette, a Lucky Strike this time. “Honey bunny, you read like a guy chasing whiskey with beer.”

Both books lay propped open, face up on my chest. “I like reading two books at once.”

She blew smoke at the moose. “You’re dead,” she said.

The moose stayed cool.

Lydia made her version of a sigh, which is more like the sound you get when you stick a knife in a full can of pop. “I’ve made a decision about this banishment deal, Sam.”

“Should I be told?”

“The way I conducted life back home didn’t work.”

“I’ll say.”

“I’m calling time out. No more connections for a while. I’m declaring myself a temporary emotional catatonic.”

I thought about this. “How’s a catatonic supposed to raise a son?”

Lydia looked down at her long fingers. “We’ll negotiate an arrangement.”

At 10:00 the news came on and we sat watching stories about people in east Idaho. Potatoes were important. Rangers in Grand Teton Park—which GroVont is smack in the middle of—were being plagued by elk poachers. Vice President Johnson was in Vietnam complaining about the food. During the sports, I didn’t recognize the names of any of the teams.

“It’s ten-thirty.”

Lydia smiled. “You mind?”

I went into the kitchen and brought back a pint of Gilbey’s gin and a two-ounce shot glass.

“You be all right?”

“Sure, I’m fine. I think I’ll sleep out here tonight and start unpacking in the morning.”

“I’m going to bed now.” I bent over and kissed her forehead. It was cool and slick. Her hand touched the back of my head.

“Your hair needs cutting.”

“Any barber around here’s going to make me look like one of them.”

“I’ll do it myself. It’ll be like we’re pioneers.”

***

I did the shower and toothbrush thing, ate a children’s multiple vitamin, snuck one of Lydia’s yellow Valiums, and put on my pajamas. I wore pajamas to bed back then. Before I flipped off my light and lay down to wait for the pill to kick in, I stood behind my open door, looking at Lydia through the crack.

She was at the window with the shot glass in her left hand and her right foot propped up on the sill. She stared out a long time. I could see the blank tightness on the side of her face, the twin knots on her neck, and a tiny throb on her temple visible clear across the room. She lifted her right hand and drew something in the fogginess her breath made on the window. I always wonder what she drew.

***

I had a dream that I was a fox and a bunch of uniformed people on horses chased me through a Southern hardwood forest.

Sam’s lungs cried out with the pain of charging headlong down the steep hillside. He tripped over a rotting log and sprawled onto his face. Rolling over quickly, he made it to his knees and crawled through the thick, thorny underbrush and into a weed-choked stream.

He turned west, splashing through the frigid water, using his paws and legs to pull himself upstream. Sam heard the dogs running up and down the bank, baying to each other and their wicked masters. Horses thrashed through the trees. He’d fooled them for the moment. Now to find a safe hole. He waded around a corner and came face to face with the blue-eyed Hitler girl astride a giant, sneering bay. She laughed and raised the rifle to her shoulder.