Skeleton Man (3 page)

Authors: Joseph Bruchac

Dark Cedars

I

CAN STILL

hear the rabbit's voice when I open my eyes. I look at the clock next to my bed. It is morning, time to get ready for school. I rummage through my suitcase and the cardboard box and find what I need. I don't feel like putting my clothes into the creepy wardrobe. When I was little my mom read me that book about the wardrobe and the lion and the witch. I wished then that I had a magic wardrobe that I could crawl into and end up in some strange land. Now that I really am in a

strange land all I want to do is crawl back home. But if there was some kind of magic door in that wardrobe, it'd probably take me someplace even worse than this.

I take my toothbrush and go into the bathroom. The only good thing about the room is that it has a bathroom connected to it. It means I don't have to go out into the hall or downstairs yet and see him. There's a bathroom built in because the former owners tried to run a bed and breakfast. There's actually an old sign leaning on its side against the house:

DARK CEDARS BED AND BREAKFAST

. The name alone is enough to scare people away from it. But I think it probably just didn't work out because this place is too far from the center of town, even though it is near Three Falls Gorge, which is the town's main place of “scenic beauty,” as our chamber of commerce puts it. When my uncle got this place he took down the sign.

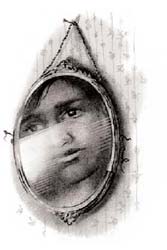

While I am in the bathroom I look at myself in the small, smoky mirror hanging over the sink. I think I have the kind of face that only a mother could love, but both my parents tell me I'm wrong. They think thick eyebrows that almost meet in the middle and ink-black hair that grows so thick I need hedge clippers

to trim it are positive assets. “There's so much you can do with that hair,” my mother says. Like get it cut short and dyed blond. My nose is okay, not bumpy or too short or too long, but my lips are too thick. My cheeks look as if I have apples stuffed in them, and when I smile my teeth are straight, but there is this gap between my incisors on top. “Braces will do wonders for you, dear.” As if, I think. I can't wait until I'm old enough to get a real makeover like they have sometimes on the shopping channel.

Still, though I'm not thrilled with how I look, I don't hate my looks. I can just see lots of room for improvement. And I know that people must like my face at least a little because whenever I smile at someone they almost always smile back. Except for my uncle. I tried smiling at him yesterday. He just studied my face like a scientist looking at some strange new bug until my smile crawled away and died. I won't try that again.

I sigh and lift up my chin. At least I don't look like a terrified victim in some slasher movie. I just look like a kid about to catch the bus. I leave the bathroom and try the door. It's not locked from the outside anymore. It never

is by this time. I peek outside carefully, my backpack with a large, empty plastic container in it over my shoulder. No sign of anyone up or down the hall.

As soon as I start down the creaky stairs, he hears me.

“Come down to breakfast,” he whispers up the stairs. He's standing at the bottom, half hidden by the old coatrack. He turns and walks away. He doesn't like me to see his face in the morning. Or ever, for that matter.

I go into the sunroom. It looks like it used to be a screened porch once. It has a floor of cold stone tiles and is connected to the back of the house. Its four big windows and sliding glass door were probably meant to let in the sun and give you a view of the garden. But there is no sun today, and there hasn't been a garden out there for a while. The places where flowers once grew are overgrown with nettles and burdock and a few small sumac trees, their leaves all red now that there's been a frost.

Although there's room in the sunroom for several tables, there's just the one. It's a glass-topped table with rusty blue metal legs. The two chairs are made of that same rusty blue metal with curlicue designs. The table is set for

one. As always, he's already eaten. At least that's what he says. I've never seen evidence of his breakfast. I see his back as he goes out the sunroom door. I'm never allowed to go out that way toward the big shed in the backyard with heavy-duty hinges on the thick, bolted doors. His toolroom, he says. I wonder again what he was doing out there last night.

“Eat your breakfast,” he calls back without turning his head. “You're looking thin.”

Then he's gone, and I take my first real breath of the day. The food on the table looks good. I'm hungry. Grapefruit, cereal, toast with butter and jam. I put my backpack under the table between my knees. I take the lid off the plastic container in the backpack and pretend to eat. But each spoonful of cereal, each slice of toast, each piece of fruit goes into the plastic box. I snap the lid onto it and close the backpack. Then I pretend to wipe my lips with the paper napkin, ball it up, and put it on the now-empty plate.

I'm just in time because, just as he's done every other day, he sticks his head out of the door of the shed to see if I've eaten my food.

“Done,” I call out in a cheery voice. Then I stand up and walk to the front door, trying to

be as calm as possible, hoping that it will not be locked. It isn't, and I escape down the walk to the corner where the school bus will arrive within five minutes. Time enough to dump the food down the storm drain at the curb edge. Let the rats deal with it.

Super paranoid, that is what you are saying now. Melodramatic. But I'm determined not to eat the food he gives me. I think he puts something into it. When I first got here I ate what he put in front of me automatically. I started having a headache and my heart was racing, and I felt like some kind of zombie. When I went to bed that night I just conked out. I didn't even dream. The next day I started my Tupperware routine. If I'd kept eating that food I'd probably be walking with my arms held out in front of me saying, “Yes, Master!” in a hollow voice whenever he spoke to me.

When the bus comes I take the first seat. Other kids are sitting with friends, but I stay by myself. This isn't the bus I used to take. No one in my class is on it, and people are still checking me out. I haven't been in a hurry to be all bright and cheery with my new busmates, either.

When the bus stops in front of the school,

though, I have to start smiling. This is my place of refuge. I'm safe here. Other kids might groan when they walk through the big front doors, but I breathe a sigh of relief. It's all so routine and boring here. I love it. Although when Laura Loh, who is my second-best friend, waves to me from her locker, I pretend not to see her and just go straight into class. I know she wants to talk to me about Greg Iverson and how cute he is and do I think he likes herâ¦and I can't bear it. For some reason I just can't think of anything to say to other kids right now, and all the stuff that used to interest me seems kind of unreal.

In our class it is Don Quixote Day. At least it is for Ms. Showbiz. We are all groaning by the time she finishes belting out her medley from

Man of La Mancha

. I'm groaning the loudest of all because it just makes me feel so safe, soâ¦normal. I feel so great that when Ms. Shabbas tells us to open our workbooks, I burst out in laughter that is so loud and inappropriate that everyone, including Ms. Shabbas, looks at me. Maureen Viola, who is my best friend and who sits two seats away, looks at me and mouths the words: “What is wrong with you?”

All of a sudden I feel as if I am about to

burst into tears. I have to put my head down on my desk. What

is

wrong with me? I'm not being tortured or anything. My uncle was kind enough to take me in. He's just a little strange. Maybe I'm the truly strange one with my worries about being drugged and my blockading my door at night and imagining what might be happening in that shed. Too much imagination, that's me.

Ms. Shabbas has a little talk with me that afternoon. She asks me to wait behind when the rest of the class is leaving for gym. She's worried about my behavior. “Is everything all right,” she pauses, “â¦at home?”

What home? That is what I want to say. I want to scream and cry and have her hold me in her arms while I sob against her shoulder. But what good would that do? So I give her my patented sunny smile.

“Everything is fine,” I say. “Really fine.”

But Ms. Shabbas doesn't smile back. “Really?” she says in a soft voice. Then she looks beyond that smile, right into my eyes as if she can see my thoughts. It's not the way my uncle does it, not like someone stealing a part of me. It's not even like an adult looking at a kid who's being unreasonable. It's the way a

true friend looks at you when they say they want to help you and really mean it.

“No,” I whisper. “It's not.”

And then I tell her. I don't tell her everything because now that I'm in school, my fears seem a little foolish, and I don't want her to think I'm being melodramatic. But I tell her how I feel, how weird it is in my uncle's house, how I really, really don't want to be there. She doesn't interrupt or ask questions. She just listens, nodding every now and then. When I'm done I feel lighter, as if I'm no longer carrying a ten-ton truck on my shoulders.

Ms. Shabbas lightly places her hands on my shoulders. She doesn't say I'm being foolish or that I should grow up.

“Sweetheart,” she says. “Thank you for telling me.” She turns slightly to write something on a card that she hands to me. “Here's my home phone and my cell phone. Call me anytime. Okay? We'll keep an eye on this together, right?”

“Right,” I say. And for the rest of the day in school things almost do seem right.

But then I take one more deep breath and the school day is over. That's bad. The only good thing is that it is Wednesday. That means I get

to come back to school tomorrow and the next day before the weekend comes, which most kids love because it means we won't have to go back to school for two days. Two whole days.

I walk home because it takes longer than the bus. I stop at a fast-food place to eat enough to kill my appetite. I don't have much money left, and I don't know what I'll do when it runs out. But I try not to worry about that now. There are other, more pressing concerns.

Finally it is getting dark. I can't avoid it anymore. I'm headed back to the house of doom.

Eat and Grow Fat

Y

OU MAY

be asking yourself what life is like for me inside that house. Are there spiderwebs everywhere? Bats and centipedes and mold on the walls? Are there chains clanking down in the cellar and ghostly moans coming from the attic?

No. Actually, aside from being dark and set back from the road, it isn't really all that spooky a place to look at. It's a hundred years old, but there are older places in town. And the house is full of modern appliances in the kitchen and the living room. Dishwasher, microwave, a television with a cable hookup. My uncle even has

a personal computer. I saw it through the open door of his study once. He spends a lot of his time in that room and I imagine he must be surfing the Net, visiting all the weirdest websites, probably.

What makes that house strange is the way it feels when you get inside it. I saw an old movie once where someone walks into a room and then the door disappears and the walls start moving in. It is something like that. And I always feel as if someone or something is looking at me, but when I turn around there's nothing there.

Then there's the way my uncle acts. Like when you'd expect him to be waiting for me, his niece, to come home, and to ask me how my day went, he's not. He's not here. There's just a note on the front door, not handwritten, but out of his laser printer. “Back later,” it reads. “Dinner in fridge.”

He's left food for me in the refrigerator for the last two nights as well. The food I'm supposed to eat is on a plate on the top shelf, ready to pop into the microwave. Anyhow, it makes it easier for me. I flip on the garbage disposal and spoon the loathsome stuff, a huge plate of spaghetti with meatballs, down the sink drain.

If I ate everything he gave meâeven if it wasn't full of drugsâI'd get as fat as a butterball turkey.

I could go into the living room and watch TV. Or one of the videos from the library of movies he has next to the VCR. There's a lot of stuff that some people think kids like to watch. Mostly Disney movies and cartoons. But I don't want to. It's the thought of having him walk in while I'm watching something. Or, even worse, of him watching me without my knowing it. I've got homework and books to read in my backpack. I'm seeing more of the school librarian now than I ever did before my parents turned up missing. Before I go upstairs I look out the kitchen window and see that the light is on in front of his shed. That either means he is out there or he forgot to turn it off. No way am I going out there to find out which it is.

I put the chair in front of my door and then take a quick bath, put on my pjs and my favorite pink robe, which I have worn just about every night for a year now. I move the bedside lamp closer so I can get the most out of its feeble light, lie down on my stomach, and breeze through my homework. Even the math problems are really no problem at all. Then I

pull out one of the books I've borrowed. It's one that Ms. Shabbas once said I just had to read because you can really identify with the heroine and it takes you somewhere else. Which is where I want to be, for sure.

It turns out that she was right. The book truly does take my mind off things. Before I know it I've read a dozen chapters. I feel like I'm on a sailing ship with the heroine. Until I start wondering what Charlotte Doyle would do if she switched places with me. And I realize that I don't know what she would do any more than I know what I should do. I put a bookmark in to keep my place, lean back on my pillow, and close my eyes. As always, at least since I've been here, I don't turn out the light. I just want to rest my eyes. I don't want to go to sleep.

But I do.

And, instantly, I am there in that same dream. I'm back in the cave, the body of a partridge warm and limp in my hands. I'm holding it out to my uncle as he crouches in his corner. Without looking over his shoulder, he reaches an arm back. I see for the first time that his fingers are long and hairy and his fingernails are thick and sharp, more like claws. He grabs the dead bird so hard that I hear its bones crack.

“I thought it would be a rabbit,” he growls. “Did you catch a rabbit?”

“No,” I say. “This is all.”

Then he begins to eat. I don't see him eat it, but I hear his teeth crunching through feathers and flesh and bones. He eats it all, growling as he swallows.

Then he reaches his arm back again. I stare at his fingers. A few small feathers from the partridge are stuck to them and the nails are red with blood.

“Hold out your arm, child,” he says.

I don't give him my arm. Instead I hold out a stick the size of my wrist. His groping hand closes about it.

“Arrggh,” he growls. “Even thinner and harder than before. No flesh at all, only bone. You must eat more, my niece. Eat and grow fat for me.”

Â

I sit up. I'm awake.

I say that aloud. “I'm awake. It was all a dream.”

But then I look around me and I see this roomâas bare and cold as the chamber of a cave. And then the

snick, snick, snick

of the locks.

No, it wasn't a dream.