Sixty Degrees North (9 page)

Read Sixty Degrees North Online

Authors: Malachy Tallack

I looked out and tried to muster the same confidence. I tried to persuade myself that Bolethe was correct. Here in Greenland, as elsewhere on the parallel, the landscape and climate continue to bring the same challenges they always have. The place continues to make demands upon the people. And while individuals might struggle to reshape themselves as society changed, perhaps the culture would still yield to those demands. I hoped it was so. I hoped that she was right.

CANADA

beside the rapids

No other nation has worked as hard to understand, define and come to terms with the north as Canada. And no other nation, surely, has such an inconsistent relationship with that place, which it both contains and embodies. Canada is a northern country and sees itself as such, particularly in relation to the United States. Around forty percent of its landmass lies north of sixty degrees â a vast area, comparable in size to the entire European Union. And yet the country's centre of balance is firmly in the south. The population â around 33 million in total â is concentrated along the southern border, and the most northerly city of more than half a million people is Edmonton, just above fifty-three degrees, the same latitude as Dublin. Only about 100,000 Canadians actually live above the sixtieth parallel â considerably fewer, in fact, than Americans.

For most in Canada, then, the north remains alien, a neighbour but a stranger. Many dream of it, but few ever wake up there. It is a place read about in books, seen in films and on television, but rarely visited. Viewed from afar, the region is tangled in contradictions. North means danger and adventure, but it also means refuge. It offers possibility and fear, beauty and horror. It is almost empty of people and yet overflowing with their imaginings.

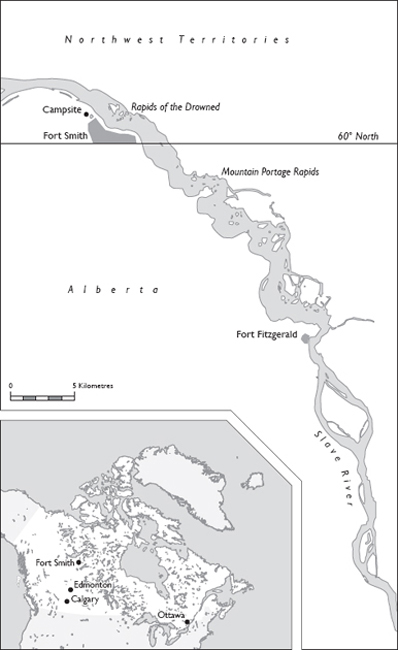

But for those who do wish to know the north, and to see it for themselves, the first difficulty is getting there, for the north is nearly always beyond the horizon. I arrived in the country in Calgary, Alberta, and my destination was the

town of Fort Smith, just inside the Northwest Territories. It was a twenty-four hour coach ride away.

A cluster of tall buildings raised like an exclamation in the flat prairie, Calgary was bathed in summer heat that afternoon. As always, my fear of flying had left me unable to sleep while in the air, and the time change had made things worse. By eight p.m., when the Greyhound bus pulled out of the depot into the clean sunlight of the streets, it had been a very long time since I had last been asleep. We drove north from the city and into the broad plains beyond. In the west, clouds were piled like rubble above the Rocky Mountains, haze-drawn on the horizon. The bus was filled with chatter, but outside the soft light of the evening lay like a blanket of quiet upon the fields.

Our first stop was Red Deer, shortly before ten p.m., just as the sun was setting. My head was cluttered with half-formed, exhausted thoughts, but I held myself awake, staring dazedly through the window. As we continued towards Edmonton an hour passed, but the memory of the sun lingered. Colours washed out, leaving behind a muted light; and as the sky softened to golden grey in the northwest, farmhouses dissolved into silhouettes â fat, black stains on the disappearing land.

At Edmonton we changed buses. It was midnight, but the depot was still full of people. Many of the passengers had brought pillows and blankets with them, and as we drove on into the darkness, voices settled into silence. I bundled up my jacket, then wedged it between the seatback and the window. Closing my eyes, I tried to sleep.

By the time we reached the town of Slave Lake at three a.m., a smear of white was in the northeast sky. Soon after, darkness began to lift again. Trees emerged from the night, close against the road, blocking the view beyond. An hour or so later the prairie returned, with fields stretched out in every direction. The farms were tidy â all straight lines

and well-kept gardens, quaint wooden houses and giant grain silos. Even the old cars had been abandoned in neat rows, lined up, perhaps, in the order in which they stopped working. A few white-tailed deer grazed here and there, and once the driver blew his horn at a pair that strayed into the road. The deer were forced into a quick decision, the right decision.

The journey north â in history, in literature, in the imagination â is a journey away from the centres of civilisation and culture, towards the unknown and the other. Margaret Atwood has written that, âTurning to ⦠face the north, we enter our own unconscious. Always, in retrospect, the journey north has the quality of a dream'. Looking out through the tinted windows of the coach, my own journey felt dreamlike. But it was not my own dream. Rather, it was as though someone else's unconscious were being projected against the glass. The honeyed light of the early morning, the procession of fields, farms, trees and towns, all seemed remote and unreal somehow. I felt disorientated and disconnected from the place outside. I observed but couldn't engage. I let the morning wash over me, hour after hour.

In 1964, the pianist Glenn Gould travelled on the Muskeg Express, a thousand-mile train journey lasting a day and two nights, from Winnipeg to Churchill, on the shores of Hudson Bay. It was his first northern journey, and on his return Gould made a radio programme about the trip.

The Idea of North

is not a documentary in any conventional sense; it is a collage of voices. Using interviews with a civil servant, a geographer, a nurse and a sociologist, all with experience of northern Canada, as well as a narrator of sorts called Wally Maclean, Gould created, to use his word, a âcontrapuntal' picture of the north. Like a choir of competing melodies, these voices rise, tumble and are lost. Ideas emerge then vanish again, as though glimpsed from a moving train. Sometimes they come through clearly, with only

the gentle clunk and clatter of the tracks in the background; other times the sounds overlap, with voices jostling for the listener's attention. Towards the programme's end the last movement of Sibelius's Fifth Symphony begins, and soon it rears up above Maclean's closing monologue, threatening to overwhelm his words, until at last there is only silence.

Going north to me means going home, and every journey I take in this direction brings with it the feeling of return. Once that feeling was an unwelcome one, reminding me always of the times I made it when I didn't wish to do so. But that has changed. It was two years after I was brought back to Shetland, aged sixteen and fatherless, that I found another way out, and another way forward. In that time, I suppose, I'd come to understand that, wherever I went from then on, Shetland would be the place to which I returned. I no longer had close family or friends elsewhere; I no longer had much to connect me with anywhere except the islands. My centre of gravity had shifted north, and though I didn't yet feel its pull, I knew that change had taken place.

It was without a great deal of enthusiasm that I decided, eventually, to go to university. Others were going, and it made sense for me to go too. It was a logical escape route. But a handful of mediocre exam results from my last year at school were not enough to get me anywhere, and so I enrolled in night-classes and took more exams. Further mediocre results followed. In the end I managed to persuade one university to take me, based on the quantity rather than the quality of my grades, I suppose. And it was my good fortune that they did, because I enjoyed almost every moment of those four years, from arrival until graduation, and I thrived there in a way that I'd failed to do at school. It was during those years in Scotland that I began to look north when I thought of home, and even to feel relief at holiday times as the train took me back up the country, towards the ferry, and a night on the North Sea.

It was a little after six a.m. when we descended into the Peace Valley. No one had spoken for three hours, though a few, like me, had sat awake throughout the night. In Peace River, dazed and dazzled, we had a break. Given ninety minutes in which to fill our stomachs and stretch our legs, I took a short walk through the centre of town, then went for coffee and breakfast in Rusty's Diner. It was just me and the waitress. A pile of steaming pancakes arrived, doused with maple syrup, and I ate them greedily, enjoying every mouthful. I felt almost refreshed.

When the time came to continue, only seven of us got back on the bus. It was raining heavily then, and we trundled into a changing landscape. Though we were still among the prairies, the agriculture was less intensive, the farms smaller, the roads less straight. Land space was shared about evenly between fields of cattle or fodder, and light, mostly deciduous woodland. In places, cows grazed among the trees.

In this country there are a multitude of lines and frontiers behind which lies the north. These frontiers have cultural and political, as well as geographical, significance, and much effort has been expended locating them. On a map it's possible to draw a series of boundaries and borders between north and south, or between ânear' and âfar north'. There is the tree line, above which the boreal forest gives way to tundra; the southern limit of permafrost; the Arctic Circle; the sixtieth parallel. Other measurements are also made. Temperature, precipitation, accessibility, population density: all are calculated, and a level of ânordicity' can be assigned, according to a scale developed in the 1970s by the geographer Louis-Edmond Hamelin.

For scientists, politicians and civil servants, such measurements are useful. They allow direct, accurate comparisons of environmental and social situations across the country.

But there is a problem. Nordicity is a southern concept â an attempt to contain what cannot truly be held â and the criteria by which it is assessed are not really measurements of northernness (other than latitude, of course); they are measurements of cold, isolation, inaccessibility and foreignness. In other words, they are calculations of how places correspond to a preconceived notion of what the north ought to be, epitomised by that most foreign of all earthly places, the North Pole. So Hamelin could write of âa 25% denordification across the North [over the past century]', as though by changing, by developing, by warming, the north can actually become less like itself.

The view from inside, though, is different. The north is all that it contains. It is a place capable of change and diversity, a place immeasurable. It holds the preconceived, yes, but also the unimagined and the unimaginable. Above all else, for those who live there, the north is home. It is neither remote nor isolated nor far away; it is the centre of the world. For me, the very arbitrariness of the sixtieth parallel, its total lack of what Hamelin called ânatural relevance', is its great advantage, making it an ideal place along which to explore the north. For the parallel is not a line by which to measure anything quantitatively, nor is it a clear border between one place and another. Instead, the parallel is entirely undefining. It allows for a plurality of norths to exist.

By mid-morning there were only trees â birch, spruce, trembling aspen, tamarack, balsam poplar â and a narrow space on either side of the road. Here and there a stretch of swampy ground emerged from the forest, or a lake, often with a beaver's lodge or two tucked up against the bank. The rain had stopped and the sky cleared by then, and the day was swollen with sunshine. I watched the trees, half-hypnotised, and thought about what lay beyond this parting of the forest. Out there, away from the road's slender imposition, lay the whole country, and more. This immense

boreal forest, of taiga and muskeg, stretches across northern Canada and Alaska, then on through Siberia, the Urals and into Scandinavia, tying the top of the planet together. It is easy to imagine stepping out among the trees here and walking within their shadow, until you emerge somewhere else entirely, some other part of the north. Except of course that you wouldn't. More likely, the person who stepped into the forest, unless they truly knew this place, would become disorientated immediately, then they would be lost, and sooner or later they would die. Nature here is a contradictory presence. It is abundant and overflowing with life, and yet threatening and hostile to our intrusions. The forest is the road's antithesis. We no longer know how to live with it, and so we pass quickly through, on our way to another clearing.