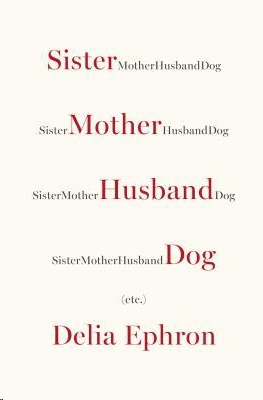

Sister Mother Husband Dog: (Etc.)

Read Sister Mother Husband Dog: (Etc.) Online

Authors: Delia Ephron

A

LSO BY

D

ELIA

E

PHRON

NOVELS

The Lion Is In

Hanging Up

Big City Eyes

NONFICTION & HUMOR

How to Eat Like a Child

Teenage Romance

Funny Sauce

Do I Have to Say Hello? Aunt Delia’s Manners Quiz

MOVIES

(with Nora Ephron)

You’ve Got Mail

This Is My Life

Mixed Nuts

Bewitched

(with Nora Ephron, Pete Dexter, and Jim Quinlan)

Michael

(with Elizabeth Chandler)

The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants

PLAYS

(with Nora Ephron)

Love, Loss, and What I Wore

(with Judith Kahan and John Forster, music and lyrics)

How to Eat Like a Child

YOUNG ADULT

Frannie in Pieces

The Girl with the Mermaid Hair

CHILDREN

The Girl Who Changed the World

Santa and Alex

My Life and Nobody Else’s

CRAFT BOOKS

(with Lorraine Bodger)

The Adventurous Crocheter

Gladrags

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA • Canada • UK • Ireland • Australia • New Zealand • India • South Africa • China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Stories previously published in the

New York Times

: “Name-Jacked” (originally titled “Hey, You Stole My Name!”), “The Banks Taketh” (originally titled “The Banks Taketh, But Don’t Giveth”), “Hit & Run,” “If My Dad Could Tweet,” “Your Order Has Been Shipped” (originally titled “The Hell of Online Shopping”)

Previously published in the

Wall Street Journal

: “Upgrade Hell”

Copyright © 2013 by Delia Ephron

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Published simultaneously in Canada

“what if a much of a which of a wind”: Copyright 1944, © 1972, 1991 by the Trustees for the E. E. Cummings Trust, from

Complete Poems: 1904–1962

by E. E. Cummings, edited by George J. Firmage. Used by permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation.

ISBN 978-1-101-63831-6

what if a much of a which of a wind

gives the truth to summer’s lie;

bloodies with dizzying leaves the sun

and yanks immortal stars awry?

E. E. CUMMINGS

T

wo weeks after my sister died, I took my dog to the doggie dermatologist. It was a hot day—nearly every day that summer of 2012 was drippingly, tropically humid—and I wasn’t sure I should bother to do this because I was exhausted and spacey from loss, but there had been a six-week wait to get an appointment, and, as all my own doctors do, the office had called two days in advance to confirm the appointment. I’d confirmed, so I felt obligated.

Honey was eating her paw. I wasn’t sure what paw-eating had to do with dermatology, although my regular vet had suggested it might be connected.

I hadn’t been paying much attention to Honey, a

small fluffy white Havanese, except to be grateful for her joyful greetings—yelps that sound like happy weeping and a dash for her squeaky toy gorilla that she paraded around with, waiting for me to applaud, which I did. All my energies had been focused on Nora. But in the middle of one night, I woke up with a start and the realization of what I’d seen but not registered: Honey eating her paw again. Rather obsessively.

Months before, I’d had her paw treated. Actually, I don’t know if it was months before—the recent past had managed to wipe out my memory of the less recent past. At some point she’d received a steroid shot from our vet. It hadn’t cured her, nor had dipping her paw in some diluted blue liquid.

Until that middle-of-the-night panic attack about Honey, I’d been uncharacteristically calm. Sleeping without assistance (no Tylenol PM or Valium, not even a glass of wine), dropping off to sleep easily, no nightmares or any dreams at all after marathon hours of anxiety in the hospital. This both confused and upset me. If I loved Nora as much as I knew I did, how could I sleep?

Was I aspiring to that fierce will she had, a refusal to show weakness? With Nora, was it more than a refusal? Was it a hatred of weakness, a distaste for it, a pride in not showing it, an unwillingness to give anyone the

satisfaction of seeing it? Perhaps all of those. Nora set the bar high in the stiff-upper-lip department. Denial was a talent she greatly admired. She could have been Gentile, except, of course, she wasn’t.

Her point of view about me was that I was a hysteric, a worrier. Was I trying to disprove her before it was too late?

When parents die, the dream dies, too—the dream that they will see you for who you really are (and, I suppose, the dream that they will ever be the parents you wish for). With sisters is it similar? Did I want Nora to acknowledge, to realize that I was as tough as she was by trying to match her, to function on all cylinders and be absolutely present during this terrifying time?

I had always been amazed at her discipline. I don’t mean as a writer. All four of us sisters—the Ephron girls, as we were known as children (Nora, Delia, Hallie, and Amy)—are disciplined. When it comes to writing, to our careers, we are our mother’s daughters: disciplined and driven. But Nora maintained her laser focus even now, confronting a deadly leukemia. My brain scrambles when I’m scared, but she could still ask doctors the tough questions and write down the answers in her graceful, confident penmanship while I could only scribble unintelligible bits in the corners of paper. (Is there nothing

sisters don’t know about each other, nothing they don’t compare, even penmanship or note-taking abilities?) Did a tiny piece of me still need to disprove her view of me as a hysteric that I always felt wasn’t fair and yet was probably, at least compared to her, accurate?

With sisters, is the competition always marching side by side with devotion? Does it get to be pure love when one of them is dying, or is the beast always hidden somewhere?

Our relationship was so firmly fixed that every day when I went to the hospital I would think,

I’ll eat when I get there

. That’s what I always thought when we wrote together at her apartment. Nora had a great refrigerator. There was often half a turkey in it or fried chicken in baggies.

Nora will have something for me to eat.

“Sick with cancer and from chemo” was not computing, the odds against her facing death, and still I was expecting to be fed, and usually there were peanut butter and jelly sandwiches that Nick (her husband, Nick Pileggi) had made that she didn’t eat and I did.

Everyone involved was steadfast. Everyone was devoted and remarkable. This woman for whom four were better than two, eight better than four, twelve better than six, the more the merrier—this woman for whom

entertaining was joy, art, obsession, and religion—was reduced to the same small rotating cast all struggling to make her happy, all praying (except none of us pray) for healthy white blood cells to sprout, for the marrow to be fertile.

Nora thanked me by sending me roses—two dozen gorgeous plump peach roses in full bloom—the sister in the hospital sending flowers to the one who was not.

I have thought a lot about this. More than anything, I think about this.

There are things a person does that you could talk about forever. They are the key. They reveal character, they unlock secrets. I think Nora’s sending me flowers was that.

It meant flat out

I love you

. Did the note say that? I’m not sure. I think it was simply,

Love, Nora

. It could have been,

xx, Nora

. My blanks in memory even include important emotional things like that. It also meant

thank you

, obviously. She was grateful for my presence, although gratitude was . . . Well, my presence wasn’t anything I needed to be thanked for. It was hard to be away from her. Leaving felt like abandonment. It felt obscene that I could leave that place and she could not. It seemed impossible. It felt dangerous to leave.

Being there was an imperative. There was no way to be anyplace else.

Nora’s sending me roses . . . not only painfully sweet, but how difficult it must have been for her to be needing care, to be dependent, vulnerable. A tiny difficult, a tiny horrible compared to the trapdoor about to open, but still not a place she was comfortable.

Don’t misunderstand. All I’m saying is those roses had subtext. A heartbreaking way to have a bit of control. To get to the place where she “lived.” The driver, not the passenger. Those roses were all that in addition to being a gift of love.

Nora was brilliant at giving. Something was always arriving by messenger. Ginger cookies she brought back from San Francisco. Peanut butter cookies from Seattle. Chocolate marshmallow drops. She would call: “These are amazing. I’m sending some down to you this very second.”

Last Christmas she gave us down jackets that my husband, Jerry, and I lived in. I not only wore mine outside all winter, but often in the kitchen when I was cooking because it was so light and warm at the same time. Once I came home from a birthday dinner. I hadn’t had any cake, and I love cake. As I walked into the lobby of

my building, I thought,

Nora will have sent me a cake

, and the doorman said, “I have a package for you.” It was my favorite, the yellow cake with pink frosting from Amy’s Bread.

So brilliant at giving. At receiving, not so much. After years of hunting in vain for something she would like for Christmas or her birthday, I pretty much picked the first possibility and let go of the impossible, that I might please her. Occasionally she might anoint something randomly. Her sporadic, unpredictable seal of approval was brilliant power-wise—power was something she had an innate understanding of—because it could keep a person hoping. A friend of hers mentioned to me with considerable pride that Nora liked her brisket.

Once I gave Nora a backpack purse. A week later I went to the store and bought one for myself. I was pretty sure that the purse I purchased was the very one I’d given her (that she’d brought back). When I wore it to her house a few weeks later, she said, “I love that, I want one.” I said, “Get real. I gave it to you, and you returned it.”

The same thing happened in the hospital.

She sent me to a store that specializes in hats for women who have had chemotherapy.

I hated that Nora was losing her hair. Even mentioning it feels like a betrayal. Her hair was gorgeous and thick and always looked fabulous. I know, the deal is to be proud, to face the world bald. It is heartbreaking to lose your hair, though compared with dying, not so much. I get it. But what about no hair

and

dying?

I hate the nickname “chemo.” I like to nickname only people or things I love. My dog has about twenty-two nicknames. My husband, at least seven. I suppose some patients want to think of chemotherapy as their friend, an ally, hence a nickname, but chemotherapy is way too cruel for a nickname. In Nora’s case, chemotherapy was more likely either not going to work or to kill rather than save. Calling chemotherapy “chemo” is like calling napalm “nappy.” Until the effects of Nora’s chemotherapy kicked in, volunteers (sweet teenaged girls who used to be called candy stripers) would show up every day and, in a sort of inept Mitt Romney-ish way, start a conversation by guessing at our relationship. “Are you sisters?” “Are you twins?” Twelve or so days into chemotherapy, a volunteer walked into the room, looked at Nora and then at me, and said to me, “Is she your mother?”

Twelve days on chemotherapy and my sister often mistaken for my twin is mistaken for my mother. That’s chemotherapy.

On her instructions, I went to the store for a particular hat. A soft three-cornered sort of cap, she told me, or words to that effect. One style seemed most likely what she meant, although perhaps not, so I bought everything. Every style they had.

All wrong, she told me. Every one.

Should I throw them away? I asked. (The store did not allow returns.)

Nora told me to toss the one I thought came closest and put the rest on the shelf. A few days later, she sent someone else for the three-cornered cap, and that person came back with the very same thing I did. She showed it to me. “Look, this is what I wanted.”

“That’s exactly what I gave you,” I said, and began frantically looking for it, couldn’t find it, and then vaguely remembered she’d told me to toss it. This had taken place only a few days earlier, but my brain was fogged. The experience was like a dream. I couldn’t be sure it happened. Really, Nora could be a total frustration, as hard to please now as ever. She was the same person, only a very sick same person, and I was grateful for that crankiness because it meant she was still there, but really all I wanted to do was to get in bed with her. I wanted to get under the covers and lie next to her. I tried it, too, but there wasn’t really room. She

had so many tubes. Why don’t they have double beds in hospitals?

If I had a hospital, I’d have double beds in it.

• • • •

Being in a hospital sucks. It sucks worse if you’re poor and not famous, because at least if you’re rich and famous you can afford a private room, and depending on your course of treatment reside on the fancy floor with a view of the river. (For most of Nora’s illness, because of the chemotherapy she was receiving, she could not stay there.) And the hospital cares. A lovely woman from patient services arrives to ask if everything is okay. Hospitals need rich people, because they are going broke. They need famous people, because lots of people want to be in the same hospital a famous person went to. Hospitals need their beds filled. Besides, no one wants anything to happen to a national treasure on his watch. And Nora was/is a national treasure.

(Verb tense has begun to confuse me. I have three sisters, I had three sisters. I have two sisters. I have three sisters. Nora is a national treasure.)

So here we are, not leaving her alone for a second in

case something goes wrong, but we have no idea what could go wrong. One morning we don’t notice that some pills that she didn’t take are sitting on the table. What do I mean, we don’t notice? We don’t notice because we don’t know we’re supposed to be looking there for that. A relatively minor mistake (although is there such a thing when a person is this sick?), but how can we possibly know all the ins and outs of the protocol of this particular chemotherapy, and besides, there are the heart meds because her heart might get wonky on the chemotherapy, and so forth and so on.

All the various specialists come in, doing their dance. There are many ramifications of this treatment, potential disasters galore. Glitches happen every day, and we have no idea what the glitch is, what it even could be. It’s not as if there’s a sniper in the woods and everyone keeps their eyes on the trees, searching for a man with a gun. No one knows where the hell they should be looking or what the hell they should be looking for until something starts beeping. Or maybe there will be no beep and we don’t know to expect one.

I felt a pervasive sense of helplessness. Of danger. Of responsibility. And a pervasive sense of guilt and unreality. How could she be sick and not me?

• • • •

She was born first. Solo. I was born a sister. Three years younger. I can only imagine her horror when I turned up. It was the first thing in her life that she had no control over.

So many women have come up to me, telling me she was their role model, and she was mine, too. I used to joke that I ran for the same class offices she did and lost as she did. Looking back, that’s a loaded comment, isn’t it? I mean, it doesn’t take a shrink. I wasn’t going to best her, upset the balance of power, my place in the world. It didn’t cross my mind until I was out of college that my job as a younger sister was not to imitate but to differentiate.

But how? We are sisters, collaborators, writer-children of writer-parents who collaborated. How am I not her? How did I find my way when she took up so much space?

It’s probably a fair generalization that famous people take up more space than people who are not famous. (They are not the only ones. Difficult children take up more space than children who are easy. Addict personalities pull focus.) People with big talent and big fame suck more oxygen out of a room. Partly it’s their nature,

and partly it’s the excitement that other people feel in their presence. Those of us who grow up around it or live in proximity have to deal with it.