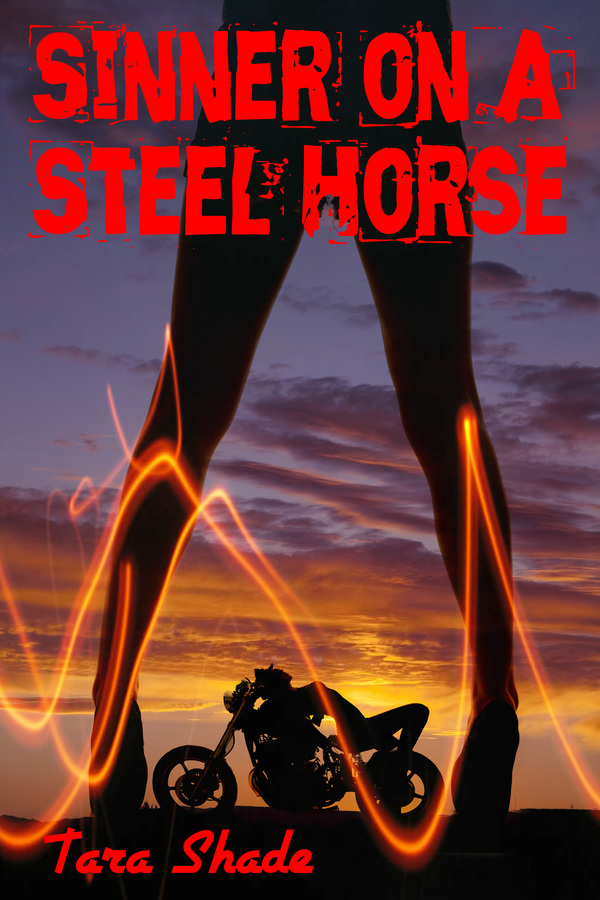

Sinner on a Steel Horse (Erotic Motorcycle Club Biker Romance)

Read Sinner on a Steel Horse (Erotic Motorcycle Club Biker Romance) Online

Authors: Tara Shade

The Lord works in mysterious ways.

That’s what my grandma always said. She used that phrase, no matter what the occasion. Out of milk at the corner store? The Lord works in mysterious ways. Flat tire? The Lord works in mysterious ways. You got laid off, your dog died, and your aunt committed suicide? Mysterious ways. Always mysterious ways.

And I’m sure that’s what she would have said about my getting pregnant at fifteen and being shuttled off to a convent as soon as it was convenient for my ultra-Catholic parents. I was a dumb little girl and even though I’m only nineteen now, I like to think I’ve grown up a little bit—even if the last few years have seen me going through the routine of prayer, community service, and tending to the convent gardens.

Let me back up a little bit. I’m sure this sounds positively medieval, so you’ll have to forgive me. My name is Marie, Marie Sanchez. My family is an old Cuban-Italian clan in New Orleans. We’ve been in the town for nearly two hundred years. Our family has produced cardinals and gangsters. Businessmen and war criminals. One of my great-great-great-great grandfathers was a lieutenant general under Robert E. Lee and was executed after the war for the way he treated Union prisoners. One of his brothers was the pastor who gave him final rites before they stood him in front of a firing squad.

When I got pregnant, it was a huge scandal. I was just a freshman at a Catholic girls’ school outside of town. It had been with a boy I met at another school’s dance. The sex—if you can even call it that—lasted less than two minutes in the back of his car before he kicked me out and I stumbled back to the dance, my lips swollen from the way he had been gnawing on my face as he humped me like a wild animal. I didn’t think much about that night until I missed my period and from then… Well…

They pulled me out of school (I would have been expelled anyway) and stuck me in a home for wayward girls that was already attached to the Lady of the Woods Convent, about thirty miles outside of New Orleans. It was understood that once I was eighteen, I would take orders and become a nun—and that’s what I did. My life, as far as I was concerned, was over. The love and warmth that my family had shown me ever since I was a child had disappeared, replaced only with their cold disapproval. Every family meal processed in silence, broken only by the terse request that one of us pass the grits or sweet potatoes. On the weekends when I went home to my parents’ house, I found myself avoiding them at all costs. I spent most of my time in my room, the family dog curled up on my feet, my nose buried in a book.

After the dog died, I stopped coming home at all. I could read just as easily at the girls’ home.

And the baby? I miscarried after only two months. It was there and gone in a flash. Sometimes, I wonder what would have become of the child—what would he or she have become? But it was pointless to wonder. Just like my grandma used to say, the Lord works in mysterious ways… I suppose.

Whenever I saw my old friends, I couldn’t help but burn with jealousy. They went through high school, going to dances, falling in love with boys, and playing sports. Then, they went to college. They would always gasp when they saw me, telling me how much I had grown up, how beautiful I had become—it must be all the clean living at the girls’ home, they would say. I would just roll my eyes and leave as soon as I could. What did being pretty matter if I were locked up, a prisoner in all but name?

I don’t even think I’m all that pretty. My mother and my sisters are much prettier—they look like old-time movie stars, with sultry looks and long, perfect blonde hair. Me, though? I look like my grandma, more Cuban than anything else, with thick dark hair, plump red lips, and smoky black eyes, plus a tan even in the winter-time. I’ve got a nice figure to be fair, but who would ever know, what with the robes and habit I had to wear every day?

I liked working in the garden at the convent, however. I felt a little bit less like a prisoner. I felt like a free woman, a woman able to go outside and do what she wants, not a girl who had been imprisoned at the age of fifteen for a stupid mistake that had never even amounted to anything. I even successfully petitioned the mother superior to expand the garden outside the walls of the convent. Under my supervision, we started growing more and more fruits and vegetables, to the point where we were beyond self-sufficient. We started bringing our produce to a farmer’s market down in New Orleans every weekend, and the money we donated to a school in the inner-city.

It was the long days, toiling in the garden—a garden that by this point had really become more of a small farm—that I began to fantasize about running away. As the sun set each evening and I began to hoe one last row for beans or carrots, I could see myself just dashing away, off into the sunset, never to be seen again. And why shouldn’t I? I was nineteen now. If I wanted to leave, there was nothing they could do to stop me. I could just disappear into that brilliant, orange setting sun and they wouldn’t be able to stop me. I could show them. I could show all of them.

So, you’re probably wondering why I didn’t do that. The truth was, I was scared. I had been first in the girls’ home and then the convent, for almost five years. Where was I going to go? I had no money of my own. My family wouldn’t take me in. I had no friends on the outside anymore. I didn’t really know how things worked… I almost felt like a time traveller, someone stranded on a desert island contemplating returning to society. It was a world I no longer knew and it scared me. At least in the convent, I could be assured that my days would be a regular routine of awaking at five, followed by a solid two hours of prayer and then a meager breakfast, before my day of work in the garden began, punctuated by breaks for meals and prayer and culminating in an evening mass before I was in bed at ten and ready to do it all over again. It was a tiring life and it didn’t leave me much time or energy to contemplate escaping.

That is, until one summer afternoon. It was blazingly hot and I was the only one working in the garden. This was how I preferred it. I had changed out of my dark robes and into jeans and a sweatshirt—still miserable in the ninety-degree weather but more comfortable than the black robes and about the most liberal thing the mother superior would allow me to wear for work outside the convent.

I was plucking some fresh tomatoes off the vine when I heard a thrashing in the bushes surrounding the garden. I turned around, suddenly concerned, gripping my trowel. There were coyotes and wild hogs in the area but they usually didn’t come around the garden, despite the prospect of fresh food. I had specifically placed the garden close to I-10, the nearest interstate and a large road, which ran parallel to the convent. The cars kept the animals away. I thought it was a stroke of genius on my part but no one else seemed to understand how brilliant it had been.

“Hey! Get out of here!” I called when the thrashing continued. If it were a coyote, I hoped it would be scared by my voice. If it were a hog, then I doubted it would be scared of anything.

And then, out of the brush, came tumbling a distinctly unhog-like and uncoyote-like figure. It was a man—a tall man at that, dressed all in black leather, with splashes of red across his body. He was wounded.

“Oh, my god!” I cried out, running to his side as he collapsed by the rutabagas. “Are you okay?”

“Jesus H. Fucking Christ, do I look okay?” he all but screamed in my face. He was handsome, with a chiseled jaw covered in a thin blonde beard, and blonde hair that he kept closely shaved on the sides of his head but had let grow out on the top. He had blue eyes, too—sparkling blue eyes, like the sea. God, but it had been a long time since I had seen the ocean…

I had to admit he didn’t look okay. I could forgive his blaspheming, considering the circumstances.

“I’m a sister at the convent just beyond this clearing. If you can walk, I’ll get you over there and we’ll call you an ambulance. Or, you know… You just stay here. I have water,” I said, my words spilling out of my mouth in a mixed jumble of syllables that barely seemed to have any meaning. I was nervous and not just because of the gravity of the situation. This was the first man who wasn’t my father or a priest that I had seen since… Christ, since only God knows when. And he was a hottie, at that.

He had to have been under thirty. It looked like he worked out. His biceps and shoulders looked like something that belong on a comic book superhero instead of on a bloodied wretch in my vegetable garden. His arms were covered in an intricate patchwork of tattoos: they seemed to portray a man’s descent into hell on a motorcycle. I knew my Dante and I rapidly identified each circle of that fiery pit.

“No, no, no…” he said finally, cutting me off. “Don’t call an ambulance. Don’t call the cops. Just…”

And then, more thrashing in the bushes. The blooded man froze and then his hand shot to his hip. He had a pistol. How had I not seen that before? He drew it fast and leveled with a shaky arm on the bushes. He had only held it for a minute before his hand was trembling bad, looking like he might drop the gun.

“Can you…” he started but I was already moving. I grabbed his arm and held it steady for him. He gave me a look, a look of solidarity and thanks, and my heart all but ascended to heaven at that look.

But any moment we might have had was interrupted by the crashing in the bushes. Finally, two men burst into my garden: both fat, both clad head to toe in leather like this man, both holding guns.

“Put ‘em down, boys, or I bury you here,” the bloodied wretch in my garden screamed. The others started to raise their own guns but my shooter roared his warning again.

“Now, you turn tail and you run, and you tell your bosses than Finn Glory is harder to kill than just that. Do you hear me?”

The interlopers hesitated, exchanging a look and then glancing at me. I didn’t know what to do or say, so I just shrugged.

“You’d better do what he says,” I screamed, suddenly, not knowing where it came from. “He’s crazy!”

“I’ll give you five seconds. Five seconds till I end you mother fuckers… Five…”

The two didn’t move.

“Four… Three… Two…”

And then they were off, into the bushes, charging back towards the highway.

“One…” Finn murmured. He titled the gun up toward the sky and pulled the trigger. I winced but it clicked empty.

“Dumbasses,” he grunted. “I can’t believe that actually worked.”

“Were they the ones that shot you?”

Finn gave me a disbelieving look.

“No, I shot myself to garner their sympathy. Of course, they were.”

“Why?”

“It’s a long, stupid story. Do you think you could get me out of the sun?”

I realized that where he lay, he was directly in the path of the brutal Louisiana sun. I dragged him to the side of the garden and cradled his head in my lap as I tipped my water bottle into his mouth.

“Goddamn, but that’s good…” he sighed as the water dribbled out of his mouth.

“Well, there’s more where that came from,” I said. “If you come back to the convent with me…”

He shook his head.

“No, no, no. I won’t go to no convent. And you won’t call no ambulance for me.”

“But… You’re wounded. You’re hurt bad.”

“I’ve had worse,” he said, shaking his head. “This is what you have to do for me: go back to that convent of yours. Get something to disinfect. Get some scissors or tweezers. Bandages. And any booze you can rustle up.”

I gave him a withering look. I didn’t like being ordered around. It was bad enough when the mother superior did it. But I didn’t like the idea of this stranger telling me what to do. And all before he had even introduced himself!

“You didn’t say the magic word,” I said in a whiny, childish voice.

“Christ, I could be dying here!”

“If you’re dying, I’ll get you an ambulance.”

“Oh, no, you won’t!” he roared as I stood and started back to the convent. “Disinfectant, tweezers, bandages, and booze!”

I found the first three in our first aid room: a make-shift infirmary that didn’t get much use at all. As you might imagine, us nuns are a pretty healthy lot. I didn’t even bother looking for the booze—I knew the mother superior might had a bottle of wine or port in her office, tucked away, but besides the wine used in mass, I doubted there was any liquor on the convent grounds.