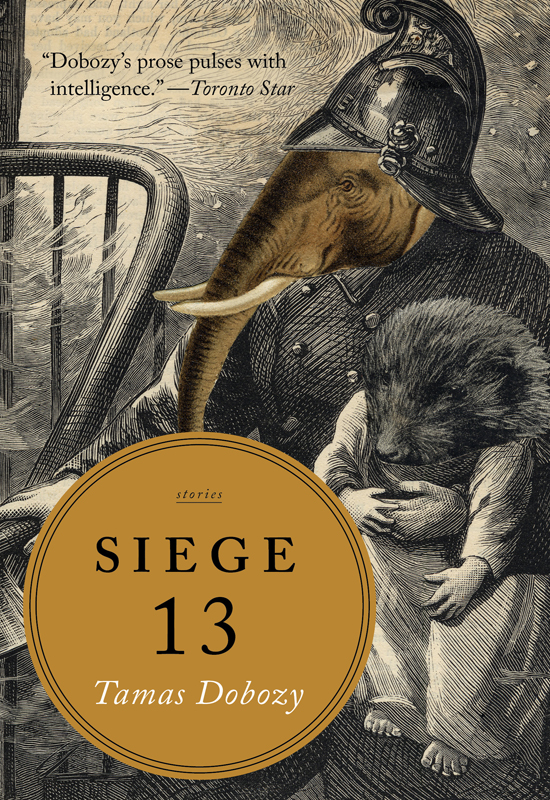

Siege 13

Authors: Tamas Dobozy

ALSO BY TAMAS DOBOZY

When X Equals Marylou

Last Notes and Other Stories

Copyright © 2012 Tamas Dobozy

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any meansâgraphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systemsâwithout the prior written permission of the publisher, or in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Dobozy, Tamas, 1969â

Siege 13 : stories / Tamas Dobozy.

Issued also in electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77102-204-0

I. Title. II. Title: Siege thirteen.

ps8557.o2218s54Â 2012Â c813'.54Â c2012-904218-8

Editor: Janice Zawerbny

Cover design: Michel Vrana

Cover image: Allan Kausch

Published by Thomas Allen Publishers,

a division of Thomas Allen & Son Limited,

390 Steelcase Road East,

Markham, Ontario l3r 1g2 Canada

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of

The Ontario Arts Council for its publishing program.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last

year invested $20.1 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada.

We acknowledge the Government of Ontario through the Ontario

Media Development Corporation's Ontario Book Initiative.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada

through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

12 13 14 15 16 5 4 3 2 1

Text printed on a 100% PCW recycled stock

Printed and bound in Canada

For two early and outstanding teachersâ

Nancy Hollmann and Robert McCallumâ

who opened all the right doors.

Both Miss Eckhart and Virgie Rainey were human beings terribly at large, roaming on the face of the earth. And there were others of themâhuman beings, roaming, like lost beasts.

â

EUDORA WELTY

, “June Recital”

Contents

The Animals of the Budapest Zoo, 1944â1945

The Restoration of the Villa Where TÃbor Kálmán Once Lived

The Selected Mug Shots of Famous Hungarian Assassins

The Ghosts of Budapest and Toronto

E WAS THE SORT OF MAN

you've seen: big and fat in an overcoat beaded with rain, cigar poking from between his jowls, staring at some vision beyond the neon and noise and commuter frenzy of Times Square.

That's how Benedek Görbe looked the last time I saw him. This was May, 2007, shortly before I left Manhattan, where I'd been living with my family for six months on a Fulbright fellowship at NYU. Görbe was an ex-boyfriend of an aunt in Budapest, though he hadn't lived in or visited Hungary for over forty years. He wrote in Hungarian every day though, along with drawing illustrations, for a series of kids' books published under the name B. Görbe by a small but quality imprint out of Brooklyn who'd hired a translator and published them in enormous folio-sized hardcovers under the title

The Atlas of Dreams

. Benjamin and Henry, my two boys, loved the books, with their pictures reminiscent of

fin de siècle

posters, stories of children climbing ladders into dreamsâendless garden cities, drifting minarets, kings shrouded in hyacinths. That was Görbe's style, not that you'd

have known it from the way he lookedâwith his stubble, pants the size of garbage bags, half-smouldering cigars, his obnoxious way of disagreeing with any opinion that wasn't his own, and sometimes, after a moment's reflection, even with that.

I was drawn to Görbe out of disappointment. The position at NYU had promised “a stimulating artistic environment,” though what it actually gave me was an office in the back of a building where a bunch of important writers were squirrelled away writing, when they were there at all. In the end I wasn't surprised; that's what writers didâ

they worked

. But this meant that when I wasn't writing I was wandering the streets, sometimes alone, sometimes with my wife, Marcy, in a dreamscape very different from the one described by Görbe. Rather than climbing up a ladder, I felt as if I'd climbed

down

one, into spaces of concrete and brick, asphalt and iron, and because it was winter it was always snowing, then rain, always torrential. I don't mean to imply that New York was dreary, only that it seemed emptied, an abandoned city, which is odd since there were people everywhereâto the point where I sometimes couldn't move along the sidewalkâall of them rushing by me as if they knew something I didn't, as if every street and avenue offered a series of doors only they could open. Because of this, because so much seemed inaccessible, New York made me feel as if I was a kid again, left alone at home for the first time, or in the house of a stranger, on a grey Sunday when there's nothing to do but search through the closets and cabinets of rooms you're not supposed to go into, never coming upon anything of interest but always hoping the next jewellry box or armoire or night-

stand will redeem the lost afternoon. New Yorkâ

my

New York that winterâwas a place of secrets.

Görbe was the biggest of them all. I called him on advice from my aunt Bea, who gave me his phone number after I complained about how few contacts I was making. She'd dated him, unbelievably enough, back in university in Budapest during the early 1960s. Görbe was an art student then, though he was also taking courses in literature and history and whatever else fired his imagination. He was “quiet and dreamy,” according to my aunt, but also “very handsome.” She compared him to Montgomery Clift. In the end, they only went out for ten months, after which Görbe dumped her for the supposed love of his life, a woman called Zella, who was majoring in psychology and who kept, according to rumour, the dream diary that would inspire Görbe's writing. Within a year of meeting Zella, Görbe left university without a degree, disappearing from my aunt's life for five years before resurfacing when his first book was published. My aunt went to the launch, wandering past posters of his illustrations, amazed to see how much Görbe had changed. Gone was the easy smile, that faraway look he sometimes had. There was something frantic about him that day, my aunt said, but he was as handsome as ever, and though he never revealed what the trouble was he seemed happy to have someone from the past to talk to. Görbe was especially bad-tempered when people who hadn't bought a book came up to him. “I was surprised to see him like that,” she said. “When I knew him in university he was so different. We were hardly adults then, but we were on the edge of itâuniversity degrees, jobs, marriages, childrenâbut whenever I was

with him it always felt to me as if we were back in the garden in Mátyásföld, playing hide-and-seek, climbing the downspout to the roof, searching for treasures in the attic.” My aunt paused on the other end of the line. “Well, he's become an important man, and maybe he could help you. It doesn't sound like you're having much luck there.” She paused again, and I could hear her shifting the phone against her face. “The number I have for him is quite old. He used to call me once in a while when he first left Hungary. I always got the feeling he really missed it here, that he didn't want to go, and he always asked me to describe what the city was like, the changes that had happened. I think it was because of Zella that he went.” I could hear her rummaging on the other end of the line. “He hasn't called me in years.”

Â

When I finally telephoned Görbe he hesitated on the line, pretending not to remember my aunt, then grew curious when I rejected his suggestion that instead of bothering him I try to meet writers at the Hungarian Cultural Center. “I'm boycotting the place,” I said, explaining how I'd gone three weeks prior to see György Konrád and afterwards spoke with the centre's director, László somebody or other, about my writing, and he'd faked interest, even enthusiasm, in that way they do so well in New York. This László person had advised me to put together an email with excerpts from my books and reviews, and to send it to him, and he'd get back to me. Hunting down the quotes and composing the email took the better part of a day, but László never respondedânot to the email, not to the follow-up, nothing. “With all the time and bother

it took, I could have taken my kids to the park,” I said, “or gone to the Met with Marcyâa hundred different things.”