Short Stories (16 page)

The man behind the bar threw his hands in the air, a gesture of extravagant disgust. “I couldn’t even do that, Goddamn it to fucking hell. When Dunn got me out of St. Mary’s, I was a whole hot week past my nineteenth birthday. Deal he made with the holy fathers said he was my legal guardian till I turned twenty-one. I couldn’t sign nothin’ without him givin’ the okay. An’ by my twenty-first birthday, goddamn Federal League was dead as shoe leather. I got screwed, an’ I didn’t even get kissed.”

“You did all right for yourself,” Mencken said, reasonable--perhaps obnoxiously reasonable--as usual. “You played your game at the highest level. You played for years and years at the next highest level. When you couldn’t play any more, you had enough under the mattress to let you get this place, and it’s not half bad, either.”

“It’s all in the breaks, all dumb fuckin’ luck,” Ruth said. “If Dunn had to sell me to the bigs when I was a kid, who knows what I coulda done? I was thirty years old by the time they changed the rules so he couldn’t keep me forever no more. I already had the start of my bay window, and my elbow was shot to shit. I didn’t say nothin’ about that--otherwise, nobody woulda bought me. But Jesus Christ, if I’d made the majors when I was nineteen, twenty years old, I coulda been Buzz Arlett.”

Every Broadway chorine thought she could start in a show. Every pug thought he could have been a champ. And every halfway decent ballplayer thought he could have been Buzz Arlett. Even a nonfan like Mencken knew his name. Back in the Twenties, people said they were two of the handful of Americans who needed no press agent. He came to Brooklyn from the Pacific Coast League in 1922. He belted home runs from both sides of the plate. He pitched every once in a while, too. And he turned the Dodgers into the powerhouse they’d been ever since. He made people forget about the Black Sox scandal that had hovered over the game since it broke at the end of the 1920 season. They called him the man who saved baseball. They called Ebbets Field the House That Buzz Built. And the owners smiled all the way to the bank.

Trying to be gentle with a man he rather liked, Mencken said, “Do you really think so? Guys like that come along once in a blue moon.”

Ruth thrust out his jaw. “I coulda, if I’d had the chance. Even when I got up to Philly, that dumbshit Fletcher who was runnin’ the team, he kept me pitchin’ an’ wouldn’t let me play the field. There I was, tryin’ to get by with junk from my bad flipper in the Baker Bowl, for Chrissakes. It ain’t even a long piss down the right-field line there. Fuck, I hit six homers there myself. For a while, that was a record for a pitcher. But they said anybody could do it there. An’ I got hit pretty hard myself, so after a season and a half they sold me to the Red Sox.”

“That was one of the teams that wanted you way back when, you said,” Mencken remarked.

“You was listenin’! Son of a bitch!” Ruth beamed at him. “Here, have one on me.” He drew another Blatz and set it in front of Mencken. The journalist finished his second one and got to work on the bonus. Ruth went on, “But when the Sox wanted me, they was good. Time I got to ‘em, they stunk worse’n the Phils. They pitched me a little, played me in the outfield and at first a little, an’ sat me on the bench a lot. I didn’t light the world on fire, so after the season they sold me down to Syracuse. ‘Cept for a month at the end of ‘32 with the Browns”--he shuddered at some dark memory--”I never made it back to the bigs again. But I coulda been hot stuff if fuckin’ Rasin came through with the cash.”

A line from Gray’s “Elegy” went through Mencken’s mind:

Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest.

A mute (or even a loudmouthed) inglorious Arlett tending bar in Baltimore? Mencken snorted. Not likely! He knew why that line occurred to him now. He’d mocked it years before:

There are no mute, inglorious Miltons, save in the imaginations of poets. The one sound test of a Milton is that he functions as a Milton.

Mencken poured down the rest of the beer and got up from his stool. “Thank you kindly, George. I expect I’ll be back again before long.”

“Any time, buddy. Thanks for lettin’ me bend your ear.” George Ruth chuckled. “This line o’ work, usually it goes the other way around.”

“I believe

that.

” Mencken put on his overcoat and gloves, then walked out into the night. Half an hour--not even--and he’d be back at the house that faced on Union Square.

Copyright © 2009 Harry Turtledove

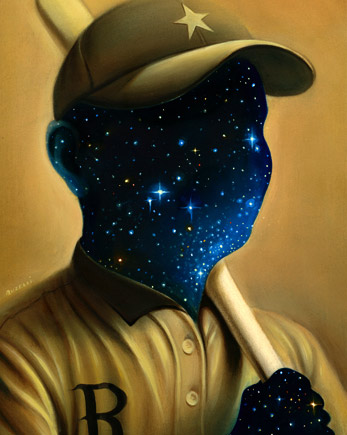

illustration by Chris Buzelli

A chilly January night in Roswell. Joe Bauman has discovered that’s normal for eastern New Mexico. It gets hot here in the summer, but winters can be a son of a bitch. That Roswell’s high up--3,600 feet--only makes the cold colder. Makes the sky clearer, too. A million stars shine down on Joe.

One of those stars is his: the big red one marking the Texaco station at 1200 West Second Street. He nods to himself in slow satisfaction. He’s had a good run, a hell of a good run, here in Roswell. The way it looks right now, he’ll settle down here and run the gas station full time when his playing days are done.

Won’t be long, either. He’ll turn thirty-two in April, about when the season starts. Ballplayers, even ones like him who never come within miles of the big time, know how sharply mortal their careers are. If he doesn’t, the ache in his knees when he turns on a fastball will remind him.

He glances down at his watch, which he wears on his right wrist--he’s a lefty all the way. It’s getting close to nine o’clock. He looks up Second Street. Then he looks down the street. No traffic either way. People here make jokes about rolling up the sidewalks after the sun goes down. With maybe 20,000 people, Roswell seems plenty big and bustling to Joe. It’s a damn sight bigger than Welch, Oklahoma, the pissant village where he was born, that’s for sure.

He could close up and go home. Chances that he’ll have any more business are pretty slim. But the sign in the rectangular iron frame says OPEN ‘TIL MIDNIGHT. He’ll stick around. You never can tell.

And it’s not as if he’s never done this before. Dorothy will be amazed if he does come home early. He’s got a TV set--a Packard Bell, just a year old--in a back room, and a beat-up rocking chair she was glad to see the last of, and a shelf with a few books in case he doesn’t feel like staring at the television. He’s got an old, humming refrigerator in there, too (he thinks of it as an icebox more often than not), with some beer. Except for a bed, all the comforts of home.

When he goes in there, he ducks to make sure he doesn’t bang his head. He’s a great big guy--six-five, maybe 235. Maybe more like 250 now, when he’s not in playing shape. Lots and lots of afternoons in the sun have weathered the skin on his face and his forearms and especially his hands.

He leaves the door to the back room open so headlights will warn him in case anybody does come in. When he turns on the TV, the picture is snowy. He needs a tall antenna to bring it in at all, because Roswell doesn’t have a station of its own, though there’s talk of getting one. It isn’t nine yet. Milton Berle isn’t on. Joe can’t stand the program that runs ahead of him. He turns the sound down to nothing. He doesn’t turn the set off: then it would have to warm up again, and he might miss something. But he does ignore it for the time being.

To kill time till Uncle Miltie’s inspired lunacy, he pulls a book off the shelf. “Oh, yeah--the weird one,” he mutters. Something called

The Supernatural Reader

, a bunch of stories put together by Groff and Lucy Conklin. Groff--there’s a handle for you.

Brand-new book, or near enough. Copyright 1953. He found it in a Salvation Army store. Cost him a dime. How can you go wrong?

Story he’s reading is called “Pickup from Olympus,” by a fellow named Pangborn. The guy in the story runs a gas station, which makes it extra interesting for Joe. And there’s a ‘37 Chevy pickup in it, and damned if he didn’t learn to drive on one of those before he went into the Navy.

But the people, if that’s what you’d call them, in the pickup . . . Joe shakes his head. “Weird,” he says again. “Really weird.” He’s the kind of guy who likes things nailed down tight.

He puts

The Supernatural Reader

back on the shelf. With a grunt, he heaves his bulk out of the rocker, walks over to the television, and twists the volume knob to the right. When he plops himself down in the chair once more, it creaks and kind of shudders. One of these days, it’ll fall apart when he does that, and leave him with his ass on the floor. But not yet. Not yet.

A chorus of men dressed the way he would be if he really spiffed himself up--dressed like actors playing service-station jockeys instead of real ones, in other words--bursts into staticky song:

Oh, we’re the men of Texaco.

We work from Maine to Mexico.

There’s nothing like this Texaco of ours;

Our show tonight is powerful,

We’ll wow you with an hourful

of howls from a showerful of stars;

We’re the merry Texaco-men!

Tonight we may be showmen;

Tomorrow we’ll be servicing your cars!

Joe sings along, even if he can’t carry a tune in a pail. Texaco is his outfit, too, even more than the Roswell Rockets are. If you’re not a big-leaguer--and sometimes even if you are--baseball is only a part-time job. He’ll get six hundred dollars a month to swing the bat this year, and a grand as a signing bonus. For a guy in a Class C league, that’s great money. But a gas station, now, a gas station is a living for the rest of his life. You get into your thirties, you start worrying about stuff like that. You’d goddamn well better, anyhow.

Out comes Milton Berle. He’s in a dress. Joe guffaws. Christ on His crutch, but Milton Berle makes an ugly broad. Joe remembers how horny he got when he was in the Navy and didn’t even see a woman for months at a time. If he’d seen one who looked like that, he would have kept right on being horny.

Or maybe not. When you’re twenty years old, what the hell are you but a hard-on with legs?

Uncle Miltie starts strumming a ukulele. If that’s not scary, his singing is. It’s way worse than Joe’s. Joe laughs fit to bust a gut. He hope the picture stays halfway decent. This is gonna be a great show.

* * *

There’s a sudden glow of headlights against the far wall of the back room. “Well, shit,” Joe mutters. He didn’t think it was real likely he’d get a customer this time of night. But he didn’t go home. Unlikely doesn’t mean impossible. Anybody who’s spent years on a baseball field will tell you that. Play long enough and you’ll see everything.

Out of the chair he comes--one more time. He doesn’t want to turn his back on Milton Berle, but he does. When you’re there to do a job, you’ve got to do it. Anybody who made it through the Depression has learned that the hard way.

Parked by the pumps is . . . Joe shakes his head, wondering about himself. Why the hell should he expect a ‘37 Chevy pickup?

That damn book,

he thinks.

That crazy story.

But the story wouldn’t get to him the way it does if he lived in Santa Fe or Lubbock. Something funny happened in Roswell a few years before he got here. He doesn’t exactly know what. The locals don’t talk about it much, not where he can overhear. They like him and everything. He knocks enough balls over the right-field fence for the ballclub, they’d better like him. Still and all, he remains half a stranger. Roswell may be bigger than Welch, Oklahoma, but it’s still a small town.

Nobody here laughs about flying-saucer yarns, though. They do in Midland and Odessa and Artesia and the other Longhorn League towns, but not in Roswell.

Anyway, in spite of his jimjams, it’s not a ‘37 Chevy pickup stopped in front of the pumps, engine ticking as it cools down. It’s an Olds Rocket 88, so new it might have just come off the floor in Albuquerque or El Paso, the two nearest cities with Oldsmobile dealerships.

As he walks around to the driver’s side, the jingle that started off the TV show pops back into his head, God knows why.

We’ll wow you with an hourful of howls from a showerful of stars.

That’s what he’s singing under his breath before the guy in the Oldsmobile rolls down the window so they can talk.

Warmer air gusts out of the car; Joe feels it against his cheek. Well, of course a baby like this will come with a heater. He’s already noticed it sports a radio antenna.

Probably has an automatic transmission, too,

he thinks.

All the expensive options.

Whoever’s in there, it’s not one of his regulars. He’s never seen this car before. And besides, his regulars are home at this time of night. If they’ve got TVs, they’re watching Uncle Miltie, same as he was. If they don’t, they’re listening to the radio or playing cards or reading a book. Or maybe they’ve already gone to bed. Not much to keep you up late in Roswell.

“What can I do for you?” he asks, trying not to sound pissed off because he’s missing his show. “Just gas? Or do you want me to look under the hood and check your tires, too?”

For a long moment, there’s no answer. He wonders if the driver savvies English. Old Mexico’s less than a hundred miles away. Roswell has a barrio. Some of the greasers are wild Rockets fans. Some of them bring their jalopies here because he plays for the team.

Because they do, he can make a stab at asking his question in Spanish. It’s crappy Spanish, sure, but maybe the guy will

comprende

. He’s just about to when the driver says, “Just gas, please. Five gallons of regular.”

Joe frowns. It’s a funny voice, half rasp, half squeak. And he wants to dig a finger into his ear. It’s as if he’s hearing the other guy inside his head, someplace way down deep. And . . . “You sure, Mister? You got a V-8 in there, you know. You really ought to feed it ethyl. Yeah, costs a couple cents more a gallon, but you make it back in performance and then some. Less engine wear, too.”

Another pause. Maybe the driver’s thinking it over. Joe eyes him, trying to pretend he’s not doing it. The fellow’s funny-looking, which is putting it mildly. Joe wonders if he is a guy. He’s sure not very big--he’s got the seat shoved all the way forward. His face is smooth as a girl’s, maybe even smoother. But he’s got on a white shirt, a jacket with lapels, sunglasses even though it’s nighttime, and a fedora with no hair--no hair at all--sticking out from under it. Joe sees there are two more in the car with him, one in front and one in back. They both look and dress like the fellow behind the wheel, poor bastards.

This pause lasts so long, Joe gets ready to try his half-assed Spanish again. Before he can, the driver says, “Regular, please. Less lead goes into the air that way.”

“Huh?” Joe says. Then he remembers ethyl is short for tetraethyl lead. It’s what they put in gas to make it knock less.

“Less lead,” the driver repeats. “Less air pollution.” He reaches out the window to point at the Texaco sign. His hand is tiny. It’s as smooth as his face. And it has only three fingers to go with the thumb. It doesn’t look as if he’s lost one in an accident or during the war. It looks as if he was born that way. He goes on, “You are a man of the star. You have the emblem. You have the song. You should understand such things.”

Was Joe singing the jingle loud enough for the guy to hear him? He doesn’t think so, especially since the Olds’s window was closed then. He’s not a hundred percent sure, though, so he doesn’t push it.

To hide his unease--that voice still seems to form in the middle of his head--he tries to turn it into a joke: “I’m not just a man of the star, Mac.” He also points to the Texaco sign. “I’m a man of the Rockets.”

The guy behind the wheel takes off his sunglasses. His eyes are enormous. They reflect light like a cat’s. Human eyes don’t do that. When they meet Joe’s, he tries to look away, but finds he can’t. They peer into him, as if through a window. He knows he should be scared, but he isn’t.

“A man of the star, and of the Rockets!” the little guy says. His eyes get bigger yet. Joe hasn’t believed they could. “Why, so you are! What a pleasant coincidence! In this vehicle, so are we.”

His two buddies wriggle and twitch as if he’s just come out with something way funnier than any Milton Berle one-liner. “What are you doing to me?” Joe hears his own voice as if from very far away--certainly from farther away than the driver’s. That should be impossible. But unlikely isn’t the same thing, a thought he’s had not long before. He tries again: “What are you going to do to me?”

One more pause from inside the Oldsmobile. It’s as if the driver has to translate even the simplest English into something he can understand.

Martian?

Joe wonders. His feet want to run, but they can’t. He’s frozen where he stands, even more than he would be by a wicked curveball.

“I am buying five gallons of regular from you,” the driver eventually answers. “That is what I am doing to you. And you are a man of the star, and of the Rockets. It is only right that you should be far-traveled in your trade, and so you shall be. And no, since you are curious, we do not speak Martian.” His friends wriggle and twitch again. He adds, “We are from farther away than that ourselves.”

What’s farther away than Mars?

That thought fills Joe’s mind as the driver puts his sunglasses back on. The second he does, most of what they’ve been talking about falls right out of Joe’s mind. He finds himself staring up at the stars, the way he was before he went in to watch Milton Berle. Boy, they look a long way off tonight! He wonders why--but not for long.

“Five gallons of regular, you said, sir?” he asks the little bald guy behind the wheel.