Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures (12 page)

Read Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures Online

Authors: Sir Roger Moore Alec Mills

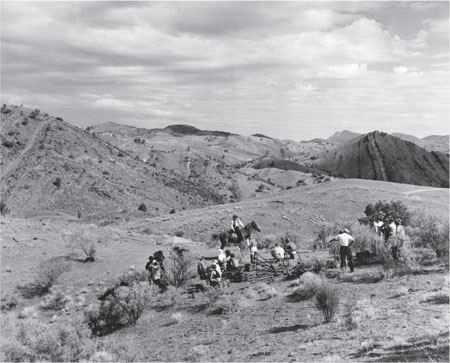

In spite of our isolated position, the sparks still had to manhandle the customary lights to the filming location – no easy task in the Australian bush.

The Flinders Mountains gave

Robbery Under Arms

a totally authentic look and feel, exactly as the Rank Organisation producers had wanted.

Unknown to Jimmy or me, the director was standing on the back of the coach, screaming at the driver to go ‘faster, faster!’ Unhappy with all the madness, the poor man still did his best to push the horses to the limit, which it seems was not enough to satisfy our director. Eventually a loud gunshot came from the rear of the coach, making the horses bolt, producing a state of shock in our traumatised driver, who was now screaming.

‘They’re out of control; I can’t stop them!’ Apparently it was every man for himself time!

With Jimmy strapped to the seat and me just about hanging on to the swaying coach, there was little chance of anyone being able to jump off; we were frozen to our positions with no intention of breaking our necks – we had to accept our fates. This frightening experience finally came to an end when one of the rear horses in the team fell, so putting a brake on the other three; later it was revealed that the two lead horses were galloping animals and had never been used in teamwork.

A real-life drama would now play out with Harry Waxman – BSC and animal lover – now offering his opinion on all this. Within seconds of the stagecoach coming to a halt my champion could barely contain himself; with steam coming out of ears, he rushed over to Jack Lee, who now got a dose of the well-known Waxman treatment:

Contraband Spain

take two! Visibly shaking from all this, Harry confirmed that ‘someone’ had fired a gun, making the horses bolt – yet another dangerous self-inflicted incident to record in a camera crew’s experience. However, the real tragedy of all this nonsense came with the final editing of the film, where the scene of galloping horses that I remember so well was cut from the film.

Another Harry ‘moment’ came when the unit carried the heavy equipment with all the necessary paraphernalia to film a scene at the summit of a steep rock-strewn hill. In the heat of the midday sun this was no small effort on everyone’s part, including the make-up department, who struggled up the hill carrying their make-up bags, chairs and umbrellas – apparently necessary protection from the burning sun for artistes. With more sweat called for, Harry asked for Vaseline. Looking into the make-up department’s bags, it would seem that they had forgotten to bring it with them as it was not really seen as a priority. Although words failed Jack Lee, the same cannot be said of my hero. I think it best to leave it there. Life could never be dull working with Harry Waxman.

The Internet Movie Database, better known to those in the industry as the IMDb, makes interesting reading in praise of the film: ‘Many of Britain’s top players and technicians travelled half-way across the world to film this Australian classic of daring adventure in its authentic locales. The result is an outdoor film of rare sweep and power which stirringly and convincingly recreates the roaring pioneer days where life was lived close to nature.’

At least this would have put a smile on Harry’s face.

The name Harry Waxman comes from my early years in the film industry; in today’s film world the name is hardly known or remembered. Even so I write here of a cinematographer who would not – could not – accept anything less than his own professional benchmark, which in hindsight is a discipline he made sure I understood. Harry’s commitment to his work was one of total dedication, an obsession which at times could go too far. Be that as it may, I still respected the guv, even understanding his fiery moments. The harmony we shared would be instrumental in the forming of my own career, not forgetting how I failed him on

House of Secrets

. Later, as a cinematographer, I would understand why certain issues drive a cameraman to frustration, though in my case with less anger.

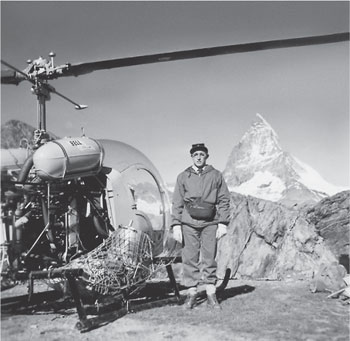

The Third Man on the Mountain

(1959). Filming in the Swiss mountains without the luxury of a camera truck meant using a variety of logistical techniques to transport the equipment to the shooting location. The mountain in the background is the Matterhorn.

One day I heard a well-known cinematographer speaking unkindly of Harry; he suggested that Harry was not a good cinematographer – very good technically, of course, but not visually. This personal opinion came from a colleague whose work I also admired, even if I thought his opinion cruel. So then it was necessary for me to defend Harry’s labours; it was a short debate where I found myself totally on Harry’s side, but at the same time I wondered if there could be some truth in the man’s comments.

There is a fine line in our profession where we are judged for our work or, in Harry’s case, his personal temperament. Admittedly, Harry’s irritations were no help to him, but one cannot deny that he was a clever technician, a cinematographer who would do his utmost to help a fellow colleague, as he did with me and others before me. Others whom I worked with would give you nothing, as you will read later in my account.

Harry’s next challenge would come while working on a film for Walt Disney,

Third Man on the Mountain

, with our location based in Zermatt, Switzerland. With Ken Annakin directing, we found ourselves filming in the shadow of the Matterhorn, a snow-covered mountain where the cool climate would always please.

One short scene required the camera to be lowered down a crevasse, pointing up at our lead actor, Michael Rennie. Due to the narrowness of the fissure, our filming window was restricted to when the sun finally hit the cinematographer’s desired position for maximum effect. With all the difficulties of capturing this in its magnificence this short scene would require careful planning before the sun finally reached the optimum position. The gap above slowly closed; already I smelt danger approaching for Harry …

A small platform built by the riggers with tubular scaffolding to support the camera was lowered down into the crevasse, along with the minimum camera equipment and four people. Looking down at what seemed a bottomless black pit – it was a long way down – Ken Annakin, Harry Waxman, Alan Hume (camera operator) and I climbed down to the rig; when the stepladder was removed our lives were in the hand of God – and the riggers’ work of art.

On our overcrowded platform any unnecessary movement would be seriously frowned upon by the riggers above, who were already concerned about this silly routine of moving around. With time getting short for Harry’s masterpiece to happen, not forgetting the constant problem of the ice moving, all that remained was to hold that position until the sun finally appeared where Harry required it. With the tripod placed at the centre of the small platform, we all positioned ourselves around the camera, allowing the director to check Alan’s framing through the camera before carefully moving around for Harry’s check, then moving once more for me to check that everything was set correctly before finally allowing Alan to move back to his position to operate the camera.

Alas, there was one unforeseen setback still to come. Harry gave me the lens aperture, which I dutifully set, making sure everything was in place. At this point the director decided on one more check through the camera; Alan moved away and we moved around one more time before we were ready to start filming. With the sun finally arriving at Harry’s required position he was over the moon; the timing was perfect.

‘ACTION! Action … action … action …’ The repeated echoes of the director’s instruction bounced off the surrounding ice walls, signalling Rennie to do his acting bit, before ‘CUT … cut … cut … cut …’ Alan gave the thumbs-up – a great shot! Harry beamed with satisfaction as the dodgy dance routine on the platform allowed me to move back to my position to check the camera gate, only to find that, unknown to me or anyone else, the director had opened the aperture to see through the camera with his final check and had forgotten to mention it!

Now, for those who have not been fortunate enough to find themselves down a crevasse, I should first explain that it can become a cosmic echo chamber where sounds become louder before fading, repeating themselves more than once. This had to be the perfect scenario for Harry’s ‘volcano’ to erupt. He had to have a go at someone. Anyone could be blamed for the terrible disaster – for political reasons he could not point the finger directly at the wicked director, Alan or me – which could only leave those poor souls above, who had nothing to do with this catastrophic situation. Even as nature’s echo chamber repeated Harry’s misuse of the English language, we still had enough time to rebuild the ice set before the sun disappeared from sight, even if it was not in the perfect position for the cinematographer.

To this day I still remember the visual spectacle below the surface, of the gentle gradation of blue ice slowly fading to black in depth. In this wonderful industry camera crews often find themselves in unusual situations, dangerous at times, others simply beautiful. Both came my way with my crevasse experience, leaving me with a memory that would stay over many years.

In this film Michael Rennie was joined by the young American actor James MacArthur, who would feature in other Disney films. A young Janet Munro claimed the female lead, with the usual names in supporting roles: James Donald, Herbert Lom, Laurence Naismith, Dorothy Maguire and Walter Fitzgerald, truly one of the great American old-timers.