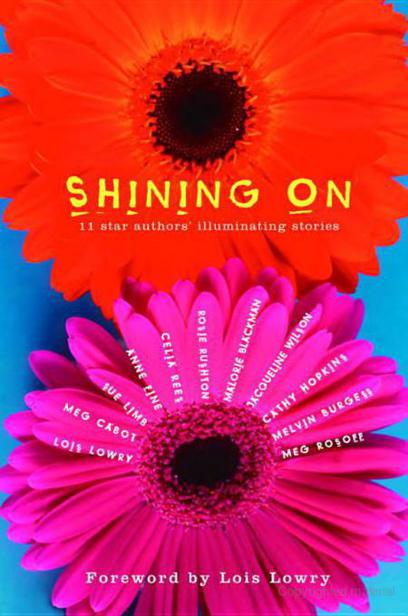

Shining On

Authors: Lois Lowry

Meg Cabot

• Allie Finklestein's Rules for Boyfriends

Anne Fine

• Getting the Message

Jacqueline Wilson

• The Bad Sister

Malorie Blackman

• Humming Through My Fingers

“T

here's got to be

somewhere

I can be just me,” a teenage boy named Gregory shouts at his mother in Anne Fine's story “Getting the Message.”

Looking for such a somewhere is a theme in all young people's lives as they mature and try to sort out who they are and where they fit in the world.

When the low blows that are part of every life interfere and mess things up, it is even harder to find the somewhere. That's what the stories in this collection are about: fighting through to find one's place.

It has always been tough to be young.

It is especially tough to be young

today.

And each of these authors has added another element to that toughness. A physical handicap. A fractured family. A troubling past. A parent who stops being one. A memory that isn't true.

There are always people—usually parents—who want

to protect youngsters, to help them along, to make things easy. It was true for me as a kid; my parents wanted things to be easy and painless for me, and safe, and I fought against them to find my own way of being. Then I did the same thing to my own children, trying to shield them from the hard things. They fought back, of course, as I once had.

These stories are about that, too: about the need young people feel to face their own conflicts; to knock down the protective barrier that their parents have placed around them; to pry open the hidden, undiscussed things and look head-on at what's really there to be battled.

“You can find the roots just under the surface almost anywhere in our garden,” the narrator, Laurence, comments in Melvin Burgess's “Coming Home” as he watches his father dig in the yard of the home that is being de-stroyed by secrets. In “Getting the Message,” Gregory in-sists that his family face the thing they've been avoiding, the question of his sexuality.

These are realistic, contemporary stories. Reading them, I was surprised to come across one that was different. A ghost story! Supernatural beings, rising from graves, taking on new forms.

What on earth has Celia Rees's “Calling the Cats” to do with all these others?

I asked myself. Then, rereading, thinking about it, I could see that the link had to do with the young protagonist, in this case a girl named Julia—called Jules—coming from a difficult, disconnected past, finding a way to lay her problems to rest at last. I read the story one final time and could see the grief in it, the

loneliness, the well-intentioned mom and the girl with the secret knowledge, the solitary thing she had to do, in order to find her own

somewhere.

Not different at all. Just one author's new way of looking at the same hard issues.

Happy endings? Some. Maybe. But youth is not a time when there are

any

endings, really. Just coming-to-terms-with. “Resigned” is a title with more than one meaning. Mom quits, in this story by Meg Rosoff. She resigns from the family. And does she rejoin it after they have all thought things over? No.

“So this is where I'm supposed to say we all lived happily ever after, but in fact we didn't—at least, not quite in the way we expected to,”

the young narrator says as the story approaches its conclusion.

This family comes to terms with how things are. They become resigned, and somehow content as well.

And maybe that is what today's young people are best at and may find in this collection: a new way of seeing things, a new way of being, of finding their place, a peek into the

“somewhere

I can be just me.” With that understanding, they can move forward; trudging, sometimes; battling, cer-tainly; but radiant, always, with the wonderful resilience that the young seem always to have.

Shining on.

—Lois Lowry

M

y mother has resigned.

Not from her job, but from being a mother. She said she'd had enough, more than enough. In actual fact, she used what my dad calls certain good old-fashioned Anglo-Saxon words that they're allowed to use and we're not. She said we could bring ourselves up from now on, she wanted no more part in it.

She said what she did all day was the laundry, the cooking, the shopping, the cleaning, the making the beds, the clearing the table, the packing and unpacking the dishwasher, the dragging everyone to ballet and piano and cello and football and swimming, not to mention school, the shouting at everyone to get ready, the making sure every-one had the right kit for the right event, the making cakes

for school cake sales, the helping with homework, the making the garden look nice, the feeding the fish we couldn't be bothered to feed, the walking the dog we'd begged to have and then ignored, the making packed lunches for school according to what we would and wouldn't eat (for those of us who have packed lunches) and then the unmaking them after school with all the things we didn't eat, the remembering dinner money (for those of us who didn't want packed lunches), and not to mention, she said, all the nagging in between.

Here she paused, which was good because we all thought the strain of talking so fast without stopping was going to make her pass out. But quick as a flash she was off again. Dad stood grinning in the corner, by the way, like all this had nothing at all to do with him, but we knew it was just a matter of time before she remembered she was married and then the you-know-what was going to hit the you-know-who.

Mum took a deep breath.

And another thing.

She had her fingers out for this one. And there weren't enough fingers in the room to list the next set of crimes.

Who did we think took care of the bank accounts, the car insurance, the life insurance, the mortgage, the tax returns, the milk bill, the charity donations, the accountant …

Here she paused again, looking around the kitchen to make absolutely certain she had our full attention and eye

contact and no one was thinking of escape—even for a minute or two—from the full force of her resentment.

We are not totally stupid, by the way. We read the tabloids often enough to know that between a mother giving a lecture of the fanatical nervous breakdown variety to her kids and Grievous Bodily Harm there is a very fine line indeed. The

Sun,

for instance, seems to specialize in stories along the lines of

Formerly average mum bludgeons family with stern lecture and tire iron, then makes cup of tea.

We three kids were doing the eye contact and respectful hangdog-look thing, maintaining that pathetic silence that makes mothers feel guilty eventually, when they're done shouting. But we had to give the old girl credit, this time she showed no sign of flagging.

She took another deep breath.

… the magazine subscriptions, the dentist appointments, the birthday parties, the Christmas dinner, the pres-ents, the nephews and nieces, the

in-laws.

As one, we swiveled to look at Dad. Mum had stopped and was looking at Dad too, whose brain you could tell was racing with possible escape routes, excuses, mitigating cir-cumstances, and of course the desire to be somewhere else entirely. He shot a single furtive glance at the back door, figured it was too far to risk making a break for it. (Mum is no slouch in the lunge-and-tackle stakes, having been a county champion lacrosse player on a team full of hairy dykes back a hundred years ago when she was in school. We knew she hadn't forgotten all the moves due to an incident

a few years ago with an attempted purse-snatching. None of us refers to it now, but word on the street is that the guy still never leaves the house.)