Shine Shine Shine (6 page)

Authors: Lydia Netzer

She finally turned and examined the screen. Her insides felt foreign, made out of plastic, manufactured elsewhere, implanted by strangers, distant.

“There,” the doctor said, and pointed to a swirl of light. “There is the baby, and there is its heart. It’s beating, you know?”

The organ that was the baby’s heart went black and white in a rhythm.

“Your baby still has lots of amniotic fluid to move around in,” said the doctor. “But the baby is in breech position. Where we’d like to see the head down here, by the birth canal, we find it up here, on top.”

“So?” asked Sunny.

“We need to stop the labor.” The doctor paused. “You didn’t want to know your baby’s gender, when we did your other ultrasound. Do you want to know now?”

“Tell me,” said Sunny.

“Your baby is a little girl.”

A girl. It was as if she couldn’t move. Her veins were cold with love and fear.

* * *

I

N THE WEEKS BEFORE

the launch of the rocket, Maxon and Sunny received requests from media outlets, asking for interviews. To populate the moon with robots and then with humans: this was potentially a story. There was no other NASA wife as perfectly presentable. There was no other NASA couple as lithe and tall. When Maxon and Sunny appeared in pictures together, there was a certain sexiness about them that led people to wonder what intrigued them about this whole moon situation. Was it really the fact that a rocket was taking robots to live up on the moon? Or was it just this handsome elegant woman and her tall, haunted astronaut man?

Cooperating with the NASA publicity department, Maxon went to New York for eighteen hours to visit the talk shows. He joked and smiled, made small talk, and comically misunderstood sexual innuendoes. But Sunny refused to do any appearances at first. She said, “I am pregnant. I can’t fly.” When the

Today

show agreed to send a crew to her house, she balked at that, too. She didn’t want to disrupt the life of her child any more than his father would disrupt it by going into space. She said this, and the people that she was talking to seemed to understand.

Finally she agreed to be interviewed on the local news in Norfolk. In this way, she would not seem to be avoiding notice. She would seem to be a trooper. That’s what they would call her. She would glitter with sacrifice. She wore her most amazing wig, the kind of style you can only achieve with a two-hundred-dollar styling appointment, or with real human hair permanently affixed in a shape. She wore coral, which was said to warm under studio lights. She wore pearls.

The network was housed in a brick building on Granby Street, unremarkable except for the news channel logo attached to its roof. Inside, the studio was a large dry room, painted dark, high ceilings hung with canister lights. Cables in braids roped from camera to set and around the floor, like black rivers across the dark room, and she picked her way across them to the set, supported on one side by Maxon.

“What are you going to wear, Maxon?” she had said that morning.

“My space suit,” he said. “That’s what I always wear when I’m astronauting.”

“You don’t even have the space suit here,” she said, too distracted with her eyebrows to acknowledge his joke.

“Well, I’m going to wear red overalls and a straw hat.”

“Oh yeah?”

“And sing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’”

“Maxon, I don’t want to do this,” she said.

“Why? You’ll do great. Look how great you are, all the time. Nothing rattles you. You’re a machine.”

“Maxon, why would you even say something like that?”

“Like what?”

Sunny peeled off an eyebrow and put it back on, a tiny bit higher up on her brow.

“I’m afraid to do it, because I’m afraid I’m going to cry or throw up or something.”

“Why?”

“You’re going into space. I’m worried. People worry about their spouses going on business trips to Kansas City.”

“Well, Kansas City is perilous. The gravity there is nine-tenths of what it is in Virginia.”

“That’s not even true.”

“I bet I can get the news guy to believe it.”

“Shut up.”

“I bet I can though.”

Eventually he had chosen to wear a NASA polo shirt and navy dockers. As they took their places on the set, she appraised his appearance and found him acceptable.

“You look good,” she told him. “Just don’t start talking about the robot that can really understand the tango and we’ll be fine.”

“You’ll be fine,” said Maxon. “The robot that can really understand the tango was my only material.”

Les Weathers bounded onto the set, fresh from hair and makeup, no doubt. He was still wearing his tissue-paper shields tucked into his collar to keep his crisp white shirt from getting smudged with foundation.

“Hey, guys! How we doing today?” he said. He grinned his enormous grin and grasped hands with first Maxon, then Sunny. His hand was warm, strong, generous. She knew that Maxon did not like to shake hands. Seeing Maxon’s sharp white fist close around Les Weathers’s suntanned paw made Sunny stare for a moment. Maxon was not tanned below the line his bicycle gloves made on his wrist.

Here is the man I married

, she thought.

He has a fist like the talons of a hawk. Here is the man I did not marry. He has the skin tone of a lion in full sun

. She wondered if they put foundation on Les Weathers’s hands.

“Great,” said Maxon. “Doing great.”

“Thank you so much for agreeing to do this interview,” he said to Maxon. Then conspiratorially, to Sunny: “Go WNFO, right? What a scoop!”

“What a scoop,” said Maxon. “Go WNFO.”

“Les, you’re so kind to bring us in, and help us share Maxon’s rocket launch with the world. I really appreciate it,” said Sunny, unleashing a radiant smile. She lowered herself into a chair between Maxon and Les Weathers, crossing her ankles under her so that her cork-wedge sandals were tidily arranged. They were going to tape the interview, show it during the evening news, when there would be the largest number of viewers. This way it would be syndicated to all the affiliates across the country. Maybe the

Today

show would pick it up after all.

Depends on how the mission goes, said the producer. Now, what does that mean, asked Sunny.

Was Les Weathers about to become famous on the back of Maxon’s mission to the moon? One big story, the correct flashing teeth all lined up in a row, and a man with nice blond hair could be headed for the big time. But only if something terrible happened. Or at least something unexpected. The fate of the anchorperson depends on a tragedy or a revolution. Sunny looked at Maxon and back at Les Weathers, and felt a ripple of nerves across her chest.

“Are you all right?” asked Les Weathers.

“Oh, it’s the pregnancy,” she said. “I’m absolutely fine. Thank you for your concern.”

The producer told them where they were to look (Les Weathers, each other) and where they were not to look (the cameras), and how they should smile and be animated.

“Act like you’re talking to a friend, at a party,” said the producer. “We’re happy here. We’re going to the moon!”

They had already been pretending Les Weathers was their friend. This would not be hard.

The interview began. What does this mean for America? What does this mean for the world? Maxon produced answers from the script he had been rehearsing. It was almost as if he were sort of a humanist, affirming a manifest destiny in the stars. He described the bright future, successfully veiling his real self for the camera. For now he was not the terse, bony guy about to leave the Earth for the first time. He was buoyant, almost cheerful. He did not say, “I rounded up a gang of robots, and I’m headed for the moon, to take it over.” He did not say, “This is the way we evolve. This is the way our culture transforms.”

Instead he said it serious: “It is a great move for mankind.” He said it droll: “We’re finally furnishing our mother-in-law suite.” He said it poetic: “Machines on the gray desert of time’s horizon.”

Sunny smiled and nodded, her knees pressed lightly together, coral cardigan wrapping the sides of her pregnant belly. She felt a droplet of sweat begin to roll under her wig. The lights were hot.

“And how do you feel about all this?” Les asked Sunny warmly.

“Les,” she said, “I married a man in love with robots. Am I really surprised he’s making off with a robot harem, to populate the sky?”

And everyone laughed. Had Sunny married a man with a job as an anchorperson and a thick arm in a neatly pressed shirt, she would have been very shocked if he made off with a robot harem, to populate the sky. She would have expected to go to Norway, to have a literal mother-in-law suite, like the kind over a garage, not the kind on an astral body.

“Let’s talk about you, Sunny Mann,” said Les Weathers. “This launch comes at a difficult time for your family.”

He gestured awkwardly, charmingly toward her huge, pregnant belly, and smiled.

“Well, Maxon’s launch was scheduled well before mine,” Sunny purred. “And the moon waits for no one.”

“But aren’t you worried, leaving your wife at this time?” he pressed. Sunny stretched out a hand and took Maxon’s in hers. It was cool and dry. He had hard hands, long strong fingers.

“Les,” said Maxon, “the timing of the mission is dependent on the orbital path of the moon, which affects everything about the launch.”

This was bullshit, Sunny knew. She felt her heart thump in her chest.

“The slightest variation in timing could cause a differential in gravitational pull that would throw off the telemetry significantly. You know, for example, the variations in Earth’s gravity. Everyone knows Kansas has nine-tenths the gravity of Virginia. In some parts of Oklahoma, it’s even less.”

“Oh,” said Les Weathers. “I guess I didn’t know that.”

Maxon produced the facial expression that communicated, “I am letting you in on a secret.” Then he winked, right at the camera, where he wasn’t even supposed to look.

“I’m not worried about my delivery,” said Sunny. “I’m not worried about Maxon’s either. He’ll get his robots to the moon, and when he comes back, there will be a new baby here to welcome him back.”

“Do you know what you’re having, a girl or a boy?”

Sunny laughed mildly. “Les, we’ve been so busy preparing for Maxon’s trip, I have not even had time to find out if this baby is human.”

6

“There are three things that robots cannot do,” wrote Maxon. Then beneath that on the page he wrote three dots, indented. Beside the first dot he wrote “Show preference without reason (LOVE)” and then “Doubt rational decisions (REGRET)” and finally “Trust data from a previously unreliable source (FORGIVE).”

Love, regret, forgive. He underscored each word with three dark lines and tapped his pen on each eyebrow three times. He hadn’t noticed that his mouth was sagging open. He was not quite thirty, the youngest astronaut at NASA by a mile.

I do what robots can’t do,

he thought.

But why do I do these things?

The spaceship traveled toward the moon. Maxon wrote with his astronaut pen. In his notebook there were hundreds of lists, thousands of bulleted points, miles of underscoring. It was a manner of thinking. He was standing in his sleeping closet, upright and belted into his bunk. The other four astronauts were in the command pod, running procedures. No one liked spending time in the sleeping closets except Maxon. He kind of enjoyed it. It was not time for the lights to go out, but the rocket to the moon was nearing the end of its first day in space.

Maxon’s list of things a robot can’t do was a short one now, pared down from a much longer list that included tough nuts like “manifest meaningful but irrational color preference” and “grieve the death of a coworker.” Maxon made his robots work better and last longer by making them as similar to humans as possible. Humans are, after all, the product of a lot of evolution. Logically and biologically, nothing works better than a human. Maxon’s premise had been that every seeming flaw, every eccentricity must express some necessary function. Maxon’s rapid blinking. Sunny’s catlike yawn. Even the sensation of freezing to death. It all matters, and makes the body work, both in singularity and in collusion with other bodies, all working together.

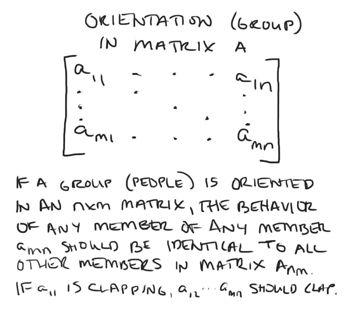

Why does a man, clapping in a theater, need the woman next to him to also be clapping? Why does a woman, rising from her seat at a baseball game, expect the man on her left to jump to his feet? Why do they do things all at once, every person in every seat, rising, clapping, cheering? Maxon had no idea. But he knew that it didn’t matter why. They do it, and there must be a reason. A failure to clap in a theater can result in odd looks, furrowed foreheads, nudged elbows. So Maxon would write:

Let anyone in any theater contradict it.

“Whatcha doin’, Genius?” asked Fred Phillips. He stuck his head into Maxon’s sleeping closet, gripping both sides of the doors as his body floated out behind.

“I’m working, Phillips,” Maxon returned.