Shame of Man (21 page)

Authors: Piers Anthony

They came to another stone wharf, docked, and climbed out. In the process he was treated to another glimpse of her handsome thighs, but he couldn't tell whether it was deliberate on her part. She might simply hold him in such contempt that she didn't care what he looked at.

There was a path up to the house, and there was indeed a lame child there. Hugh did what he did best, and not only charmed the child and his family with flute music; he brought out one of the simpler wooden flutes he had crafted and gave it to the boy, teaching him how to blow notes on it. A lame boy should have a lot of time to practice, and the lad did seem to catch on readily. The family was most appreciative. The man, Itti, was of the warrior class, garbed in red, and surely prominent. He gave Hugh two sheep's knucklebones that would be excellent for gambling, and had fair

value in their own right. It seemed likely that there would be no objections, the next time Hugh's tour brought them to this region.

Then it was time to return to the village. Hugh followed Sis back down to the boat, noting the way her hips swayed as she walked. Now he had little remaining doubt: she was doing it deliberately. He knew because Anne was expert in the art of becoming sexually appealing, whether in a dance or otherwise. So, it seemed, was this woman. But what was her interest in him?

They got in the boat and paddled back toward the mainland wharf. But when they were farthest from either the island or the mainland shores, Sis paused in her paddling. “Turn around,” she said.

Whatever she was up to, now it was about to clarify. The mission to play for the crippled child had been legitimate, but Sis must have volunteered to do it, so that she could achieve her own purpose. He now suspected what that purpose was, but remained mystified by its rationale. He laid his paddle down and turned around on the seat.

She was in the process of stripping away her clothing. He watched as the top and bottom came off, leaving her naked body glistening in the light of the declining sun. She was splendid in all her physical parts. It was the mental part that kept him wary.

He eyed the whole and the details. “You plan to swim?” he inquired after a moment.

She got right to the point. “I have a desire for you, wrong hand. Play your melodies on this body.”

She had called him “wrong hand.” So she had noticed. The strangest thing was that he had a feeling that he had done something like this in the past, though it was not true. There was something about her body and her manner that not only attracted him, it made him seem to remember having sex with her. That was impossible, as he had never seen her before yesterday. So from where could such a memory come? Perhaps from the similar sultry women who liked his music and who found the distinction of wrong-handedness appealing.

Meanwhile his mouth was saying the obvious. “I am married. My wife is beautiful.”

“But I can give you more. I am hot and lusty.” She inhaled, licking her lips and spreading her knees.

“I need no more than she offers.” But the woman was stirring his desire.

“Why not try me and see?” She leaned forward so that her breasts shifted form.

“My wife wouldn't like it.” Especially not with a woman like this.

“Then she need not know.” She got off the seat and approached him, squatting so as not to rock the craft. That made her even more intriguing, as perhaps she knew.

She had ready answers, having evidently rehearsed this scene. But what

was her real motive? He had acted like an ignorant duffer in everything except his skill with music, a performance hardly calculated to incite a woman's admiration or romantic spirit. He suspected that she had had this in mind from the outset. It surely wasn't passing passion that motivated her, yet she seemed ready to give him what any other man—and Hugh himself—desired. Why?

He decided on a direct approach. “What is your interest in me? I know I have not come across as a masterful man.”

Her eyes narrowed as she paused in her approach. “So you

were

pretending. I wondered. You know the ways of deceit.”

“You have not answered my question.”

“I am jealous of your wife. I want to take you from her.” She resumed motion.

That seemed true, but only part of the truth. Sis was certainly jealous of Anne's beauty, but she should be just as jealous of Seed's beauty, and she wasn't going after Seed's husband. There had to be some other motive.

Meanwhile he had to act, lest she succeed in seducing him. It was time to turn this off. “No. I will not be with you.”

She squinted at him again, and saw his resolution. “If you seek to avoid me, I will claim that you tried to force me. You are new to this tribe, and wrong-handed; they will believe me rather than you.” Now she had reached him, and laid her hand on his arm. “You would not want that.”

“Something other than passion for me motivates you,” he said, casting off her hand.

There was a flicker of something other than anger in her face. But she quickly masked it. “Hit me, if you wish.” She caught at him again.

Then suddenly it came clear. “Anne!” he cried. “You are decoying me away from Anne. So that she is unprotected.”

Now her teeth showed in a snarling smile. “Too late for her, I think.”

Hugh leaned forward, put his arms around her, clasped her close, lifted, and heaved. Suddenly she was out of the boat and splashing in the water. He grabbed a paddle and scrambled to the boat's rear seat, where control was better.

Sis surfaced, her hair plastered, spittingly furious. “You can't get away!” She reached for the boat.

He lifted the paddle like a club. “Touch it, and I'll bash you. Then you'll have reason to accuse me—if you don't drown.”

Her eyes met his for a moment. Then her hand withdrew. “So you are indeed a man,” she said.

“I am indeed.” He plunged the paddle into the water and drove the boat forward. He stroked again, sculling, leaving the woman behind.

After several strokes he glanced back. She was swimming for the shore. She was moving well, as he had thought she might. He had harmed no more than her dignity—and perhaps not much of that.

Then he realized that her clothing was still in the boat. Well, he would leave it at the corral.

He readily outdistanced the woman, for even a clumsy boat was better than swimming, when managed competently. He moved on to the shore, drew the boat out, and went for the horses. He considered, as he approached them; should he free the other one, and send her running away, so that Sis had no mount? No, he had a significant lead; his business would be done before she caught up.

Soon he was on his mare, guiding her without words. She responded eagerly to his competence, fairly flying across the terrain. Such rapport between man and mount was wonderful; both enjoyed it. It was sad the way other cultures did not understand such use of horses. They thought that meat was all they offered.

He reached the village quickly enough, for he had wasted no time. Seed was there, minding his children and hers. “Where is Anne?” he called.

“Bub came to guide her to you,” Seed replied. “To join you with the lame boy, as you asked. Didn't you see her on the way?”

“No.” And he knew why: Bub had no intention of bringing Anne near her husband. His design was of a quite different nature. “Which way did they go?” He suppressed the echo of Sis's words:

Too late for her.

“To the north, where he had the horses.” Now Seed looked alarmed, but her voice was controlled so as not to alarm the children. “Bub has a house farther north.”

Horses. Hugh's growing tension eased a notch. “So they were riding.”

“Yes. Perhaps you can find them. The children will be safe here with me.”

“Thank you. How long ago did they leave?”

Seed made an indication of two close fingers toward the sun, showing that it had not traveled far. “Not long.” Hugh nodded, turned his mare north and put her into a trot.

Naturally Bub and Anne were not by the local corral. But Hugh could see the recent tracks of the horses going north. They were walking, because Anne would have had the sense to do what Hugh had, concealing her excellent riding ability. Bub would have told her that this was where Hugh had gone, but she would have been cautious, knowing that the man was of doubtful character. She would have taken time to get to know her horse. Then, if the trip turned out to be false, she would ride swiftly away, and Bub would not catch her.

But if the man had had the wit to get her to dismount, to separate her from the horse, and to attack her without warning . . .

Well, even then Anne was not a likely victim. Because she was a dancer. Still, Hugh fingered his dagger nervously. He did not want vengeance, he wanted his wife safe.

Then he saw dust rising to the north. A single horse was coming, galloping south, experdy guided. Soon he recognized the flowing dark hair

of a woman, and soon after that he confirmed that it was Anne. They drew up together and reached out to touch hands. Then they turned their mounts south, walking.

“Sis?” she inquired.

“Naked in the lake. Bub?”

“Indisposed in a field.”

No more needed to be said; they understood each other. They returned to the village.

Later Anne gave another class in dancing. She showed a new step, difficult for many women but beautiful in execution because of the flash of flesh it showed. It was a quick step away from the partner, a spin around, and an unusually high kick forward. “Take care that you are not too close to your man,” she cautioned the women. “It could be unfortunate.”

Hugh played the music, nodding to himself. He suspected that Bub had stood too close, and been the recipient of that swift waist-high kick. Then he would have been inclined to drop to the ground for a time, suffering the pain only a man could feel. He would be unlikely to speak of the matter to others thereafter. But he would probably never again approach a dancer carelessly.

While the adults danced, the children played with their toys. Chip showed off his wagon, and pretended to hitch it to a horse, being intrigued with the foolish notion. Mina was proud of her unique design, pressed into the hardening clay by her belt cord. The other children were impressed too, by both the notion of hitching horses to wagons and of decorating pottery in such manner. But of course they were too young to appreciate why such things weren't feasible for serious use. It was a good session.

The Yamnaya tribe was one of a group of proto-Indo-European cultures that had domesticated the horse. This made them highly mobile, and they expanded over a wide area of the steppes. They also had wagons, but it seems that these were at first moved by manpower; their horses were too small to be used for such brute work. However, in time they figured out how to connect more than one horse at a time to a single wagon, and this magnified their mobility. This may be the explanation for their subsequent greater expansion, not merely across the thinly populated steppe but into the settled agricultural regions. A change in climate may have helped shift the balance of effectiveness toward the pastoral peoples, making more grazing land.

At any rate, expand they did, all across western Asia and Europe and on to India. We know this because their corded ware spread out, identifying them, and their languages displaced those of prior cultures in these regions. Today the Indo-European family of languages constitutes about half of all languages in the world, and governs most of the world's territory. Only China, southeast Asia, the south Pacific islands, northern Africa, and Asia Minor are excluded, apart from isolated spot cultures such as the Basques of Europe. Were this considered

an empire, it would be the greatest ever known. We conjecture that the use of the horse, at first to ride, then to haul, and finally in battle, gave such an advantage to the Indo-Europeans that they were able not only to conquer the more settled societies, but to dominate them indefinitely, so that their languages came to prevail, just as English (one of the Indo-European languages) is spreading today. The economies of power were Indo-European, not because of any particular leader or ideology, but because they had a better way. The horse culture was here to stay.

CHAPTER 10

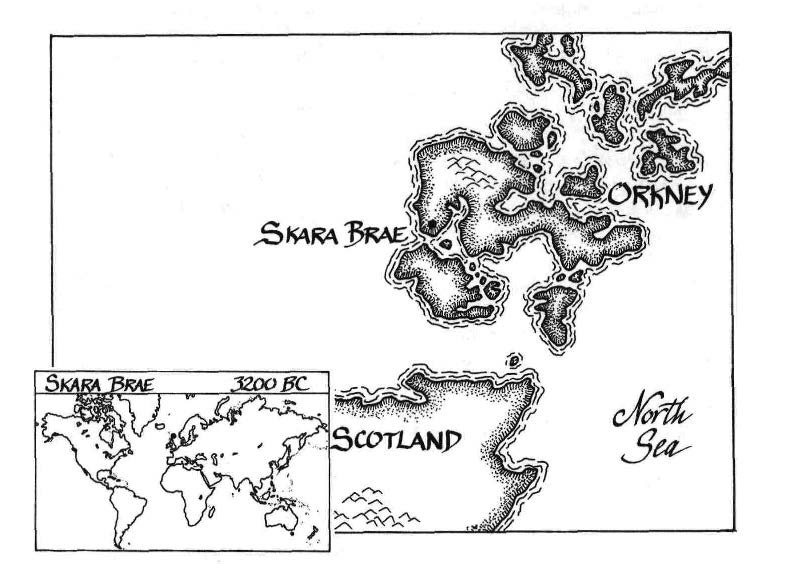

SKARA BRAE

A bad storm buried a village in the Orkney Islands north of Scotland about 1500 B.C. Another storm uncovered it more than three thousand years later, in

A.D.

1850. Thus an untouched prehistoric community site was revealed. Its buildings survived because they were hidden

—

and because they were stone. Had there been enough wood there for building, we might never have learned of it, because wood disintegrates with time. Had it been exposed, the stone might have been taken for other purposes. So this was one of the accidents of preservation: a village of six to ten houses made of slate, beside the cold North

Sea. Skara Brae (not “Scary Bra"). They would not have called it that, of course, but we shall consider this to be our translation of their own name for it. This was the fringe of what we call the Megalithic culture, whose earliest monuments predated those of Egypt and spread across much of Europe. The best known example is Stonehenge in southern England, but there are others, and there were perhaps a larger number of Woodhenges whose ruins have been lost to history.Who were these mighty ancient builders? What was the purpose in their circles of giant stones, some of which might weigh as much as sixty tons? How did these primitive people quarry, move, and erect such monsters? Gradually the wild speculations have given way to more solid conjectures. Skara Brae and the associated Stones of Stennes perhaps show the way. The time is circa 3200

B.C

., near the beginning of this settlement.

O

NE might have thought that things would be quiet the night before the annual Festival of Stones, in preparation for the strenuous activity to come. But there was too much excitement, especially among the children, for this year Chip and Mina were being allowed to attend. They were seven and five respectively, and had shown that they were able to walk a distance when they had to. So instead of being farmed out to their older neighbor Lil, to join Lil's grandchildren, they got to share the great adventure. They were supposed to rest, but were irrepressibly excited.

The sheep, however, were another matter. One had to be slaughtered and dressed, to be taken along; this was Hugh's contribution to the effort. The others Lil would watch, in return for the wool of one of them next season. And Hugh's eight-year-old nephew Jay would come to occupy the house, to care for the dog and see that no rats got into their supply of barley.

So all was ready. All they had to do was get a good night's rest. And that seemed to be almost impossible. The children could not relax. Anne served them a good supper of boiled limpets, because not only were the little shellfish plentiful and tasty, their knuckle-sized disk-shaped shells usually gave the children much entertainment. They would roll them at each other, and make high piles of them, and pretend they were jewelry or imitation teeth. But even this ploy was ineffective this time; Chip and Mina remained as animated as new lambs. They simply would not settle down on their cushion beds for long enough to fall asleep.

Finally Hugh did what always worked: he brought out his bone flute. He played, and Anne danced and sang, and both children were instantly enraptured. Of course they had to respect music, because it was special to the family, but it was more than that; they really did respond to it at a deep level. Soon both were asleep.

“And now what do

we

do to settle down?” Anne inquired as they let their music die gently away.

“What do you think, woman?” Hugh said, hauling her into him. So they made love, and it was effective; they slept thereafter.

In the morning Hugh was up first. He wrapped his sheepskin cloak about himself, called the dog awake, and went outside to urinate. They had a drained toilet closet inside, but he didn't bother to use it; it was for the convenience of women and children.

The house was joined to the next, and there was a narrow alley between them. There were six houses in all, each with its family of four to twelve people. In summer the interconnections didn't much matter, but in winter, when the fierce storms could last for days, they made community life practical. In fact it was this strong sense of community that enabled them to carry through the bad weather.

The dog led the way, long familiar with the route. They emerged from the tight cluster and walked out onto the shell midden against which the village was made. People had used this area for a long time before the present clan had occupied the site; they didn't know or care who those others had been. Their refuse had long since settled and become land, useful to brace the present houses. There were stories of harder times and stories of better times in the past, but all that mattered was how it was now.

He checked the house from outside, as he always did. The stone wall was secure, of course, but the thatch over the whalebone roof beams could get out of order and had to be watched. The last thing they wanted was a leak discovered only during a storm.

He saw Bil emerge similarly from the alley. Hugh gave the man time to complete his private business, then went over. “Your children settle well?” he inquired.

Bil laughed. “No more than yours!” Because Bil had two who would be going along too. The two men were close, for a reason that was not a fit matter for discussion: Hugh had had an early relationship with Fay, who had left him for Bub, but then left Bub for Bil. It was as if Bil had finished Hugh's unfinished business. Their children Wil and Faye matched Hugh's in ages.

“Start with the sun one fist high?” Hugh inquired, naming the time they had agreed on.

“Yes.” Bil turned to check his own thatch, and Hugh returned to his house with the dog.

Anne was up now, wrapped in her sheepwool gown, breaking bread into chunks for breakfast. She hadn't bothered with a fire; there wasn't time. Her hair was in a loose tangle; she always made sure of the food before tending to herself. “You are beautiful,” he told her.

She made a face, pulling her hair across in a momentary veil, then smiled. “Eat before the children get it,” she said, setting out a chunk and a bowl of sheepcurds.

He sat at the stone bench beside the center hearth, in the wan light from the small window, and clipped the rock-hard bread into the soft curd. This was like the relation of man to woman, he thought, the soft complementing the hard. It was a good way.

Anne retired to the private closet to catch up on herself. He admired her rounded rear as she got down to pass through the low access portal. Any crisis that appeared now would be Hugh's responsibility, until she emerged.

As he gnawed on the softened edge of bread, he gazed around the chamber. He was proud of this house, which he had maintained since taking it over. It was large though his family was small, because it served also as a community center. He and Anne often entertained the others when it was not possible to work, and that diversion could be the difference between unity and fragmentation. The main bed was against the center of one wall, with its cushions and heath to soften the stone, and fleece blanket for warmth. The cupboard was against another wall, with its crocks of food and jugs of water and sacks of grain: their security against drought and freeze.

The children slept to the left of the main bed, in the corner by the closets. He focused on them for a time. Chip's brown hair matched Hugh's own, and indeed he was clearly of their family. But little Mina's glossy black hair was something else, shinier than Anne's tresses. Anne styled the girl's hair to match her own, and the two did have a similarity of appearance. But Mina was not a blood child; they had adopted her as a foundling baby, and never regretted it. She had been a delight throughout.

Yet it was more than that. Mina had an affinity for the spirits. Even bad spirits did not molest the family when Mina was there, and sometimes good spirits gave warning in subtle ways when mischief was brewing. That was an advantage they could never have anticipated when they saved the baby from death by exposure. They had no idea who her natural mother was; they had found her during a stone festival, when the whole island congregated. Perhaps she had simply been a gift of the spirits.

As if conscious of his gaze, the little girl stirred, waking. That jogged Chip awake too. In a moment the two were scrambling competitively to be the first to reach the private closet.

“Hold, people!” Hugh cried warningly. “Your mother's there now.”

So they charged the bench instead, ready to gnaw on bread. “Are we still really going?” Mina asked, her eyes big and wonderful.

“We are still really going,” he agreed.

She clapped her hands and flung her little arms around his neck, kissing him wetly on the cheek. Then she grabbed a chunk of bread and began to gnaw enthusiastically.

Anne emerged, her appearance improved. Chip charged the closet.

Mina, on the wrong side of the bench, seeing herself hopelessly behind, elected to ignore it. Her turn would come. Already she was learning to be graciously feminine when covering her losses.

They moved out before the sun was one fist high. Hugh lagged just long enough to be sure the dog didn't come. Other families were doing the same, making a rare crowding in the passage. They filed out to the gathering place.

Chip extended his arm and made a fist at the sun. “Hey—it's more than one fist up!” he exclaimed. “We're late!”

Hugh extended his own fist. “No we aren't. Your fist is smaller than mine.”

“Oh.” But the boy pouted only a moment. There was just too much excitement to allow small errors to remain long in mind.

When the sun was right, by Bil's fist, they set off: Six men, ten striplings, one woman, three maidens, and five children. Half the village, leaving behind most of the women, children, and old folk. Because this was not simply a celebration; it was the important working ceremony of the year. It was the Festival of Stones.

The distance to the ceremonial center was not far; a man traveling at a running jog could have reached it by noon. But though every person traveling was healthy, there were constraints. Two men were hauling a wagon loaded with food, blankets, coiled ropes, and special clothing made for the occasion, and sometimes that wagon needed extra hands, for the trail was narrow in places and steep in others. The children were full of energy, but would slow as the novelty wore off. The woman—Anne—and maidens would be tending to the children, so could not forge swiftly ahead even if they were so inclined. They were not so inclined, because they preferred to appear dainty—and the men preferred to have them appear so, at least for this event. Because their appearance at the festival could enhance their prospects for marriage. So it would be near dusk before this party reached the center.

They proceeded inland, roughly southeast, veering as necessary to avoid difficult terrain. The men shifted off on wagon hauling duty, making three teams; they, at least had no concern about getting sweaty. Hugh took the left side, so that his dominant hand was outside, in case of anything unexpected. Others in the village didn't care about his sinister handedness, but sometimes strangers did, so he masked it as a matter of course. Even so, Chip had been known to get into a fight because of it. Hugh had mixed feelings about that, but overall he was satisfied that neither child resembled him in that respect.

They stopped for lunch, and the women brought out smoked coalfish and fresh berries while the maidens fetched bags of cold water from a nearby stream. Anne made the children lie down to rest, and by this time they were

tired enough to obey. It was a nice day, with just enough wind to make the heat of effort reasonable.

In late afternoon they reached the center. This was an open level region from which the hills all around could be seen. The children were especially impressed with the view of the steep cliffs of the large island to the south, which could be seen beyond a lake.

A great circle was marked on the turf, surrounded by a curving ditch enclosing a region fifty paces across. A single enormous stone poked upright from the ground, three times the height of a man. Tomorrow they would erect a second smaller stone.

The folk of other villages were arriving similarly. Bil directed his group to a suitable campsite, then nodded to Hugh. Hugh went in search of the clan leader, whose tent he thought he saw on the northern edge of the plain, by the lake there. He needed to check in and give the count of working men from Skara Brae, and also the maidens.

“Daddy!”

He turned, startled. There was Mina running after him, her black tresses flying. She was about the cutest little girl he could imagine, and in another decade would surely make a beautiful woman. But what was her concern? He waited for her to reach him.

“What is it?” he asked as she arrived. “Did you lose your mother?”

“No,” she panted. “I think—I think you need me.”

“I always needed you, precious child,” he said, smiling.

“No, I mean really,” she insisted. “For the spirits.”

He looked back to the camp, and saw Anne. He waved to her, to confirm that Mina had reached him safely. “Then come along,” he agreed, taking the little hand. Mina was at times unpredictable, but always agreeable, and she did indeed have a feel for the spirits. She was in her sweet way a haunted child.