Shadow Theatre (30 page)

Authors: Fiona Cheong

HAT I REMEMBER about that morning is the moonlight, slipping so white through the branches of the

HAT I REMEMBER about that morning is the moonlight, slipping so white through the branches of the

jacaranda onto the cement floor of the hotel room balcony, and

the air smelling sweet like a rebirth, like freedom. Dawn at the

edges of my mind, but nowhere around us that I could see, for

outside were only the dark fields and groves of trees furrowed

so prettily by the moonlight, and the kampong, hidden by the

trees, where the boy who had set up the meeting for me was

sleeping, and the river, a black ribbon winding through the

moonlight, in which the kampong families bathed and washed

their things and where their sewer water emptied, all into the same river. Not that I had asked the boy about it. All I had asked

him was how well he knew the man who was going to handle

the whole thing-I wanted to know if he was trustworthy, of

course. The man, I mean, not the boy. I trusted the boy, perhaps

because he was still a boy, no older than fourteen or fifteen, I

would think. My brother's age, or the age my brother would

have been (the doctors couldn't explain what made him stop

breathing six months after he was born, except to say sometimes that sort of thing happened)-"He's my uncle," the boy

had said to me in answer to my question, and then he had

added, "You want to know what I'm going to do with the

money?" And that was when he had told me about the kampong

and how we rich Singaporeans were spoiled, complaining about

hardship when we had never tasted true hardship. And then he

had apologized, of course-I think he may have had a slight

crush on me. But he could also see I was genuinely distressed,

because I was. You didn't get that sort of information from

brochures, or from history books for that matter, in those days.

And I was only twenty-three, and still very unexposed.

Not that the boy was trying to get me to change my

mind-why would he? He wanted the money. But if there had

been a moment when I could have turned back, it would have

been that moment, while he was talking about the kampong and

I wondered, briefly only, if I myself was asking for too much. So

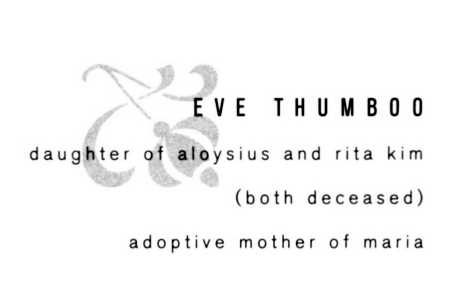

why didn't I turn back? Was your Auntie Eve born with evil

already in her soul?

You will have to decide, my darling.

IT WAS AI.VIN who had booked our room. Cameron Highlands

was one of his haunts, you see, ever since he was a boy. I, on the

other hand, had never left Singapore before our honeymoon.

Anywhere else he could have chosen for us to go, I would have

been as much of a stranger as I was at that hotel, so the locale didn't matter. And the room they had given us was lovely, very

modern, very clean, and as the hotel was on a slope, we had that

view of the countryside that I was admiring in the moonlight on

the morning I was to meet the boy's uncle.

I was on the balcony only a few minutes. Someone may have

seen me, but what would anyone have thought? Just another rich

man's wife, or his daughter, who was having trouble sleeping.

And if another woman had seen me? She may have suspected

more, but I wouldn't think it would have been enough. If a

woman had seen me, she herself might have been some tycoon's

wife or daughter, staying at the hotel on holiday with her family. Unless she was a prostitute, or one of the maids ... Not that

this possibility of being noticed or recognized had even entered

my mind, of course. Not that I had much of a plan, you see. Nor

would anyone step forward later to say that he or she had seen

me on the balcony around four o'clock that morning, or that

shortly after that, he or she had seen a woman leaving the hotel

by herself and walking off in the direction of the kampong and

the river, carrying a small bundle by her side, too large to be a

purse and too small to be any kind of food sack, the kind of bundle you might make from a wide silk scarf, for instance, if your

purse couldn't hold all the dollar notes you needed to take with

you. Not that I was ever at risk of getting caught, because

Halimah's medicine was undetectable.

Are you sure you want to hear more? Now you've gone and

kachaued whomever you could find, are you at all closer to the

truth? You must decide, that's right.

All right, then. Bring that candle over here, and close your

eyes. Because the truth, my darling, is seldom the first thing we see,

but the dust of conversations, floating in breath, just out of sight.

H E WA S WAITING for me underneath the banyan tree, just as the

boy had promised. Wearing a white songkok like a haji, a white kurta, and white trousers, moonlight swaying at his feet as the

banyan leaves shook at my approach. No shoes. I could draw you

his face, but what would be the point? He may not look the same

anymore, and if years from now you want to go looking for him,

if you feel you must, remember what he may be, for the boy may

have lied to me, and he, being of that certain nature, can change

his face, become a woman if he wants to, even return as a child,

as Pontianak, as his daughter.

You follow what I'm saying? Once you ask, it's only polite

to listen, follow the spaces between our words, surrender.

Otherwise, don't ask.

Yes, bring another candle, and check the latch on that window over there, please. A wind is about to come. Hear how the

birds are holding their breath.

So. E E E WAS waiting for me underneath the banyan tree. Because

of the way he looked at me, and the raw hunger in his voice when

he asked, "Where is your husband now?" as if I weren't the one paying him, even with my inexperience, I was already wondering if the

boy had lied, if perhaps I had been lured into their trap, if I was in

danger. But then I remembered Halimah. She would have warned

me, so since she hadn't, I became unafraid, only remaining wary.

Yes, of course I felt disappointed with the boy, disappointed

because there was something cannibalistic in the man's smile

when he unbuttoned my blouse with his eyes, his teeth like a

razor on my throat. Even if he was the boy's uncle, the boy had

lied to me in another way, you see, and because he was the age

my brother would have been, because I was so innocent, because

right up to my wedding day, I had been allowed out only with

my amahs (my mother, you remember, died giving birth to my

brother), I wanted to believe boys were not like men, that at

fourteen or fifteen, a boy had not yet become my husband, or

other women's husbands, or my father. But I could not idle the morning away, feeling disappointed. I had business to take care

of, and dawn was just over the horizon, a vague lightening of the

sky beyond the river, a purplish tint in the shadows around us.

"Where is your husband now?" the man asked again.

Somewhere I couldn't see, a rooster had begun to crow.

Yes, I remember his voice. I will always remember his voice,

and I remember how I answered the question. "Sleeping." Flatly,

without background, not like a wife or a daughter or a mistress,

and not even like a servant or an amah. I said it as if Alvin

weren't my husband, as if I were a hotel maid who cleaned his

room, or one of those immigrant girls removing trays from a

table he had sat at in a hawker center. I spoke as if he were a

passing customer, with a stranger's face like the faces of other

customers, hair, nose, eyes, mouth, cheekbones, nothing to

make him stand out, nothing to endear him to me. As if I myself

had crumbled into sand, chips of granite, filaments of rain now

starting to rattle the trees.

"Razim told you about the payment?"

"Yes. Are you going to do it yourself?"

"What? Oh, you mean the accident. No, of course not. I

have someone better, a tourist." He looked up at the rain, only

a thin drizzle coming through the banyan leaves. "You are sure

your husband will remain asleep?"

I wasn't sure if he was testing me to see if I would speak

truthfully to him, if Razim had told him about Halimah's powder or not. Not that Razim knew about Halimah, but he knew I

had a powder from a bomoh. So I said simply, "Yes, I am sure."

Then, feeling bolder once more at the memory of Halimah, I

asked him if Razim had specified that he could only watch, that

he was not to come near me or touch me.

He smiled, and that, too, I will always remember, for even

someone so depraved can have a beautiful smile.

'That's what they like to do," he said. 'They like to watch

only. Come."

T I 1 E R I: W I R E FIVE others, besides Razim's uncle. We may as

well call him Razim's uncle as any other name. You can hear from

his speech he was not your usual kampong fellow, although he

was Malay, or so he looked to me. The other five were foreigners, all with blond hair. I thought they were brothers. Perhaps

they were, perhaps not. I couldn't tell them apart, except for one

who had the grace to blush when I began undressing.

The other woman, I don't remember her face at all, but she

was Eurasian, too. As it turned out, she was the reason the five

brothers, the foreigners, were interested in our show, because of

her operation, you see, because this other woman used to be a man

and what the foreigners had paid for was to see what happened if

a woman like that made love to another woman, to the kind of

woman they themselves might make love to, a woman like me.

Yes, we touched wherever they wanted us to touch, as long

as they kept their own hands away. It was only a show, my darling. Worse things than that can happen in this life, and worse

things have already happened. All the wars that men wage

among themselves, girls always get trapped in them, and yes,

boys, too. Always the children, and often, women.

It was only a show, no longer than an hour. It wasn't hard to

get through. All the while my gaze was fixed on the slope of the

ceiling, or on the chinks between the planks of wood that made

up the walls of the room. Only for one disturbing moment did I

wonder if Razim was in the house, if perhaps this was his house,

too, and then I managed to disentangle myself from the thought,

and for the rest of the hour, my soul was sitting on the rooftop in

the rain, drinking in my coming freedom in the wet dawn.

WAS II I I E R E. No other way? The truth, as I've said, is seldom the

first thing we see. Dust is all around us, not only in your dreams. Once, two young men held down a child, prodded and poked

into her as if she were a doll, choked her on her own vomit, and

one of the men was already a father, and the other, his best

friend, my Alvin. This happened, and there were no witnesses,

only a brother who would never be forgiven for wandering away

from his sister to watch some older boys playing soccer in the

field next-door to the community center (the brother, five years

old, had been told to stay with his sister, whose body would be

found two weeks later), and only your mother, who when she

became pregnant with you, began to dream of a girl lost in a field

of sugar cane, who kept calling to her.

That was why your mother came home. She thought the

girl was you, your soul waiting for you here. She didn't know

about your sister until the two of you were born, your sister

first, then you. The placenta tore when we pulled your sister

out, leaving only a wrinkled scrap curled around her foot. But

you came out slippery like a tadpole, and almost fully sheathed.