Seven-Tenths (24 page)

Authors: James Hamilton-Paterson

*

No-limits apnea uses a weighted sled rather than a rock for descent, and an air bag for ascent. The current record is held by the Belgian, Patrick Musimu, who in 2005 was pulled down to 209 metres (686 feet) in the Red Sea and survived.

*

This passage originates in a lecture given by Mark Cousins at the Architectural Association in London on 23 November 1990.

*

Tennyson,

Idylls of the King,

‘The Coming of Arthur’, 1.140.

William Buckland’s

Bridgewater Treatise

maintained that the presence of fossils embedded in sedimentary rocks was definitive proof of Noah’s Flood. This work, really a series of lectures, was published in the 1830s, the same decade as Charles Lyell’s

Principles of Geology

, whose radical conclusions could scarcely have been more different. By Buckland’s day the question of the Earth’s age was keenly debated. The natural sciences had evolved to the point where a more serious answer was needed than Mosaic chronology could provide. The supremacy of the biblical version of Earth’s creation had already been challenged a century earlier by Newtonians like the Comte de Buffon. Eighteenth-century science had gained enough insight into geological processes to enable it not so much to speculate about how old the Earth was but to wonder how all the vast, slow procedures of erosion and sedimentation and the laying down of fossil beds could have been squeezed into the mere 6,000 or so years allowed by Scripture.

It is possible to argue that until Christianity there was no such thing as time. That is, until after the life of Christ, people’s notion of time would have been largely cyclical, based on the regular recurrence of seasonal and astronomical phenomena. Longer periods were simultaneously precise and vague, being measured by carefully preserved familial dynasties such as the lengthy genealogies in the Old Testament. To small rural societies, the Earth was unchanging, as old as legend, as old as their creation myths. It was not possible to apply any external timescale to it because one did not exist. This view of time changed radically with the coming of Christianity. Suddenly, time stopped being a slow, circular continuity and became an ‘arrow’, linear, flowing in a single direction from Creation to the Last Judgement. Christ had come as a man in fulfilment of a

prophecy, and as a man he had died. He could only do so once, so his life was just an episode – though a momentous one – in a single temporal trajectory which was carrying all mankind with it towards the great Millennium.

Once this idea had taken root, theologians began examining the Judaic scriptures with new motives. They were now less interested in the genealogies as evidence of pedigree than as ways of calculating how many years had elapsed since God had created the world so lately visited by his son. Theophilus of Antioch put Creation at 5529

BC

; Julius Africanus at 5500

BC

. This was eventually reduced by Martin Luther to 4000

BC

and finally Archbishop Ussher produced a date of scholarly precision, 4004

BC

, which stood as the problem’s definitive solution. This date gained such wide acceptance it was printed in most English bibles with chronologies. It can be found even today in some fundamentalist bibles.

This firm date of 4004

BC

had all sorts of consequences for the way in which people thought and looked at the world and soon produced intolerable strains in the burgeoning natural sciences. Even archaeologists began worrying about how societies as complex as that of ancient Egypt could have evolved so quickly. To some it was clear that the oldest pyramids dated from around 3000

BC

, only a scant thousand years after the beginning of the World According to Archbishop Ussher. Geology, meanwhile, had progressed to where the publication of Lyell’s

Principles of Geology

in 1833 made it clear it was no longer necessary to invoke six-day acts of creation or great-flood catastrophism in order to explain the Earth’s structures. All that were needed were the ordinary processes which anyone could observe, plus almost unlimited quantities of time. Once it was assumed that fossil beds could be millions of years old instead of a maximum of 6,000 it created a sort of conceptual breathing space in which many things suddenly began to make sense.

No matter how horrible or absurd their positions may be, there is always an element of poignancy about diehards. It was therefore both comic and pitiful to see a scientist like Philip Gosse confront evidence such as Lyell’s and be unable to relinquish his own fundamentalist

position. Instead, he went into contortions which effectively destroyed him, bringing down on his fervent and well-meaning head the ridicule even of churchmen. In 1857, only six years after his school zoology textbook, he published

Omphalos

which, as the title implies, had as its centre of gravity the question of the navel. Adam must have had a navel because God had created him as the genotype of the human race. Since Adam had no mother, his navel was surely more exemplary than functional. Similarly, had Adam cut down one of the trees in the Garden of Eden he would have found annual growth rings, although they had been there only days. To deal with this problem Gosse claimed that some things were ‘prochronic’ or ‘pre’-Time. Adam’s navel and the tree rings were prochronic. Because the first chicken had been created fully fledged, the putative egg from which it hadn’t in fact hatched was equally prochronic. So also were fossils. God, for reasons best known to himself, must deliberately have ‘salted’ the Earth with fossils in order to make it seem older, perhaps, and maybe even to test the faith of later scientists, especially geologists.

The derision which greeted this pretty notion completely baffled poor Gosse. The Revd Charles Kingsley, whose

The Water Babies

showed he was himself quite capable of imaginative extravagance, was particularly forthright. In his own

Glaucus

he commented bleakly: ‘If Scripture can only be vindicated by such an outrage to common sense and fact, then I will give up my Scripture, and stand by common sense.’ Gosse was not completely on his own, of course. William Buckland went on thinking that The Flood was a perfectly satisfactory explanation for fossils. But Gosse was a well-known figure, and his flounderings in the name of science made him something of a lightning conductor. Others, too, were disconcerted and depressed by a rationalism which seemed unaesthetic as much as irreligious. Ruskin wrote plaintively in a letter of 1851: ‘If only the Geologists would leave me alone, I could do very well, but those dreadful Hammers! I hear the clink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verses.’

In the mid-nineteenth century what science badly needed was a reliable temporal yardstick by which to obtain a sensible age for the Earth, and in the following 100 years many were proposed and tried.

Having gone down a coal mine and noticed the higher temperature, Lord Kelvin concluded that it ought to be possible to work backwards using the temperature gradient and extrapolate a date for when the Earth was in its original completely molten state. He suggested an age of 20–40 million years, later putting it at 100 million years. Some geologists considered sedimentation rates, using the annual deposits known as varved layers rather like tree rings. William Beebe thought salt would prove a reliable measure. In

Half

Mile Down

he wrote: ‘The chemical composition of blood, both in the constituent salts and their proportion in solution, is strangely similar to that of sea water.’ The only difference was that our blood is three times less saline than the sea. ‘So all we have to do is calculate back and find the time when the ocean was only one-third as salt as the present … and we will know [the exact moment of] our marine emancipation.’ True, this would not be the age of the Earth itself, but it was still a useful date to fix. Unfortunately it now seems that the ocean’s salinity has never varied very much and that prehistoric seawater was not greatly different from modern. This also put paid to the idea for calculating the age of the oceans by assuming they started as fresh water and working out how long it would have taken to leach out that amount of salt from the Earth’s crust.

It was only with the discovery that radioactive elements decay at strict rates that a reliable geological or cosmic ‘clock’ was found. Nowadays the age of the Earth is usually given as 4.7 billion years, but even this is not final. In fact, all cosmological dates are under constant revision and may always be so. It is unclear whether the construct of time’s linear ‘arrow’ can survive quantum imponderables, but in short timescales at least it seems to point to a cheerless future for the human race. The discovery that the universe is not static meant that the Earth cannot last indefinitely, though the precise manner of its end is conjectural. In the 1930s the theory propounded by Sir James Jeans and Sir Arthur Eddington of the ‘Heat Death’ of the universe was received with the kind of glum consternation that represents less an absolute belief (for few people understood the physics) than a general shift in the recognition of what is plausible. Public moments like these can be looked back on

as forming yet another step in a sequence which included the great debates centring around the writings of men such as Gosse, Darwin and Lyell. The trend was inexorable. The human race was slipping out of the hands of God and into a quite other universe determined by the second law of thermodynamics.

Nowadays

Homo

’s fate is commonly thought to be even worse than that, being in his own hands. Death by nuclear destruction, environmental pollution, global warming or in a demographic gridlock of overpopulation are fluently forecast by prophets of one sort or another. Serious minds can be found expending as much effort in predicting man’s future span as in trying to date his past. In the face of all this, the choice of a dignified intellectual stance seems limited. The fossil record might be fragmentary, but its message is all too plain. Mass extinction for one reason or another has occurred many times, no doubt more often than we know. It could happen again tomorrow without violating a single natural law. Since the mindless optimism of religion cannot qualify as a serious position, rational man is left in possession of his true intellectual birthright, an exalted stoicism. Bertrand Russell, having read Jeans and Eddington’s theory, put it succinctly: ‘Only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair can the soul’s habitation henceforth safely be built.’

*

The sun is definitely lower now. The freezing thermocline in whose

upwelling the swimmer was briefly caught has moved on. He is thirsty

and weary and finds himself becalmed in an edgy resignation. He has

done his purposeful but unrewarded swimming about. Now he wants

to preserve his strength for staying alive as long as possible. He is

already thinking ahead to another day’s floating, taking it for granted

that he will survive the night.

For the first time he is considering the possibility of rescue. He has

abandoned the idea of finding his boat. He accepts that his direction

less first attempts to search for it are more likely to have separated him

still further. Even if he did happen to be looking in the right quarter

when stern or prow or the tip of an outrigger reared up on a wave there

are surely too many intervening waves for anything to be visible now.

He does have a plan of sorts, if that is not too intentional a word for

such an impotent state as his. At nightfall, he knows, this area becomes

a major local fishing ground. True, many of the boats will have engines

over whose unsilenced blatter his shouts may not be heard. But many

of the poorer fishermen stop their engines to save fuel and just drift,

while the poorest of all will come out here under sail. Since sound

travels well over water the swimmer has high hopes that someone will

hear.

In the meantime he is once again examining the sunlit depths on the

extreme off-chance of rescue from another source. He has heard legends

of dolphins helping shipwrecked mariners, of a strange bond which

sometimes leads them to aid distressed humans, even occasionally

towing them to safety. The sea is empty, however. It seems to him it is

a long time since he has even glimpsed a dolphin, several weeks at least.

He can remember when it was hardly possible to look at the sea for five

minutes in these parts without their breaking the surface, leaping in

pairs. Only three or four years ago he would probably have been

surrounded by the curious and playful creatures. Now there is nothing.

The sea is empty even of their squeaks. The swimmer knows their

absence is most likely due to the very fishermen at whose hands he

is hoping for deliverance. Why should any remaining dolphin come

within a mile of him? Of what use now to invoke ‘strange bonds’ in

so self-interested a fashion when the deal had always been so cruelly

one-sided?

*

Quoted in John D. Barrow,

The World within the World

(1988).

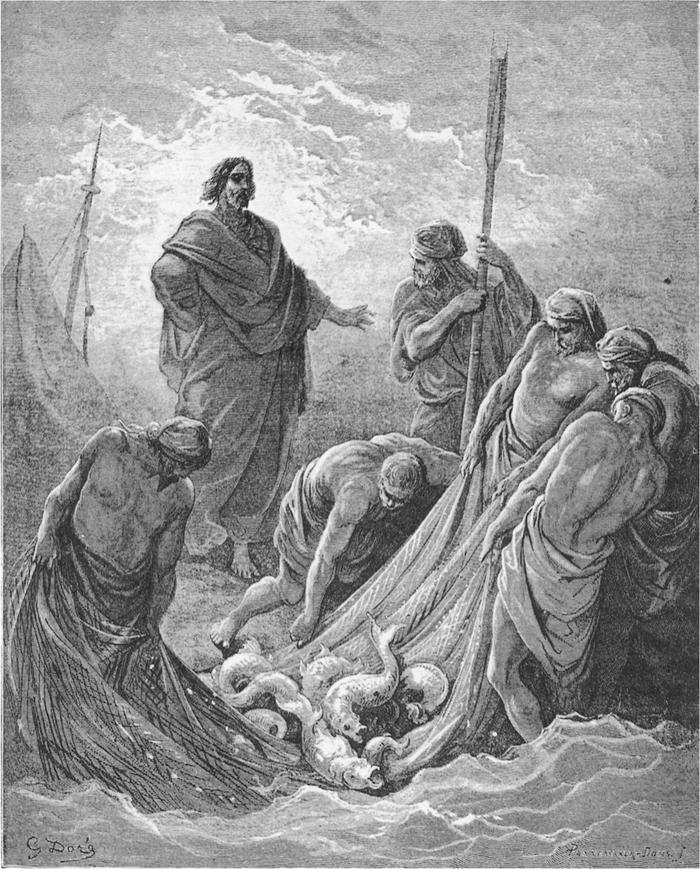

‘From henceforth thou shalt catch men.’ Quota-free fishing on the Sea of Galilee.