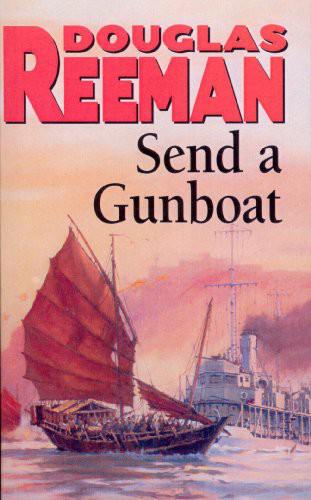

Send a Gunboat (1960)

| Send a Gunboat (1960) | |

| Reeman, Douglas | |

| (1960) | |

| Tags: | WWII/Navel/Fiction WWII/Navel/Fictionttt |

HMS Wagtail is a river gunboat, a ship seemingly at the end of her useful life, lying in a Hong Kong dockyard awaiting her last summons to the breakers' yard. Commander Justin Rolfe is also seemingly at the end of his useful naval life, an embittered man, brooding and angry from a court-martial verdict. Then the offshore island of Santu is threatened with invasion from the Chinese mainland. The small British community must be brought out and Commander Rolfe and the Wagtail are ordered to the island. The job is regarded with sullen resentment by his crew, but to Rolfe, and even the ship, it is a job that offers the chance of a reprieve and a restoration of self respect.

HMS

Wagtail

is a river gunboat, a ship seemingly at the end of her useful life, lying in a Hong Kong dockyard awaiting her last summons to the breakers' yard. Commander Justin Rolfe is also seemingly at the end of his useful naval life, an embittered man, brooding and angry from a court-martial verdict. Then the offshore island of Santu is threatened with invasion from the Chinese mainland. The small British community must be brought out and Commander Rolfe and the Wagtail are ordered to the island. The job is regarded with sullen resentment by his crew, but to Rolfe, and even the ship, it is a job that offers the chance of a reprieve and a restoration of self respect.

Douglas Reeman did convoy duty in the navy in the Atlantic, the Arctic, and the North Sea. He has written over thirty novels under his own name and more than twenty best-selling historical novels featuring Richard Bolitho under the pseudonym Alexander Kent.

About the Book

HMS

Wagtail

is a river gunboat, a ship seemingly at the end of her useful life, lying in a Hong Kong dockyard awaiting her last summons to the breakers’ yard.

Commander Justin Rolfe is also seemingly at the end of his useful naval life, an embittered man, brooding and angry from a court-martial verdict.

Then the offshore island of Santu is threatened with invasion from the Chinese mainland. The small British community must be brought out and Commander Rolfe and the

Wagtail

are ordered to the island. The job is regarded with sullen resentment by his crew, but to Rolfe, and even the ship, it is a job that offers the chance of a reprieve and a restoration of self-respect.

Douglas Reeman joined the Navy in 1941. He did convoy duty in the Atlantic, Arctic and the North Sea, and later served in motor torpedo boats. As he says, ‘I am always asked to account for the perennial appeal of the sea story, and its enduring appeal for people of so many nationalities and cultures. It would seem that the eternal and sometimes elusive triangle of man, ship and ocean, particularly under the stress of war, produces the best qualities of courage and compassion, irrespective of the rights and wrongs of the conflict . . . The sea has no understanding of righteous or unjust causes. It is the common enemy, respected by all who serve on it, ignored at their peril.’

Reeman has written over thirty novels under his own name and more than twenty best-selling historical novels, featuring Richard Bolitho and his nephew Adam Bolitho, under the pseudonym Alexander Kent.

A Prayer for the Ship

High Water

Dive in the Sun

The Hostile Shore

The Last Raider

With Blood and Iron

HMS Saracen

Path of the Storm

The Deep Silence

The Pride and the Anguish

To Risks Unknown

The Greatest Enemy

Rendezvous – South Atlantic

Go In and Sink!

The Destroyers

Surface with Daring

Strike From the Sea

A Ship Must Die

Torpedo Run

Badge of Glory

The First to Land

The Volunteers

The Iron Pirate

In Danger’s Hour

The White Guns

Killing Ground

The Horizon

Sunset

A Dawn Like Thunder

Battlecruiser

Dust on the Sea

For Valour

To Winifred with love

Douglas Reeman

It is better to light one small candle than to curse the darkness.

CONFUCIUS

ANOTHER LONG SUMMER

was beginning, but even the dry, heavy breath which fanned the glittering water of Hong Kong’s main anchorage, failed to quell the normal air of feverish activity and mounting noise, which surged back and forth in a weird ever-changing and confusing pattern.

The hard, unblinking sun fixed the white buildings around the harbour in a swimming heat-haze, making the windows glitter and twist, as if in pain. Even the mean, squalid little streets, crammed with their surging streams of colourful humanity, could not escape, although the shopfronts crouched in permanent semi-darkness. Only the uneven tops of the smart new skyscrapers, and the distant roofs of the sleepy hill-property seemed free from the stifling pressure of noise and dirt.

From the harbour these buildings made a pleasant backdrop, distance helping to mould them into a live and vital picture for the newcomer. Old mixed with new. The great temple, overshadowed by the giant building of the Communist China Bank, and the neat white bungalows of the civil servants, lumped almost alongside the peeling tin roof of a canning factory.

The contrast was apparent too on the water. It was never quite still, as in any other harbour. It was always jammed with its countless beetle-like craft, from bobbing ungainly sampans, and the battered water-taxis, to the tall, ancient junks, which glided like great bats amongst the other craft with unerring accuracy and calm.

A P. & O. liner, her derricks clanking and jerking, lay alongside the main quay, her rails jammed with excited faces, and gay dresses, and two wharves away, the squat, eagle-crested ferry steamer sidled slowly out into the stream, about to start on yet another journey across the blue water to Macao.

Clear of the main waterway, and aloof from the bustling life of the harbour, the cruiser towered like a giant pale-grey rock, the soft wavelets shimmering and reflecting against her lofty

sides. As she pulled gently at her mooring buoys, the dancing lights flickered from the brass fittings about the spotless decks, while the long taut awnings flung back the hard glare to the clear skies above.

Few figures moved about the decks, for apart from the heat, and the obvious boredom of looking at the same view, it was Sunday, and the ship’s company at least showed no desire to follow the example of the busy people around them.

A marine sentry paced stolidly at the head of the accommodation ladder, his red face shadowed by the wide sweep of his tropical helmet, the gleaming rifle already hot in his grasp.

The Officer-of-the-Day, immaculate in white drill, tucked the long telescope under his arm, and licked his lips, savouring the taste of gin, and trying to remember what he had just had for lunch. Occasionally he glanced carefully at the shaded skylight in the middle of the cruiser’s wide quarterdeck, as if expecting a sign to tell him of the movements of the Admiral beneath it. For this was the Flagship, and as the thought crossed his sweating mind, the officer squinted aloft to the limp flag at the masthead. The flag of Admiral Commanding the China Inshore Squadron.

He stepped back gratefully under the awning, his eyes resting momentarily on the two American destroyers which were moored side-by-side about half a mile away. Even from here he could clearly discern the wild blare of jazz which poured unceasingly from their deck loudspeakers to join the other discordant noises around them.

A police boat slid quietly between two moored junks, and prowled uneasily alongside one of the fishing yawls. The puppet-like figures waved and nodded in the age-old game of question and answer, until the launch, apparently satisfied, continued on its way.

The officer stiffened, as the Engineering Officer and the Doctor, in rumpled civilian clothes, clattered down the accommodation ladder to a waiting boat, their golf clubs rattling behind them. He envied them their freedom, but not to play golf. He whistled softly, watching the boat scud away for the shore, his mind toying dreamily with the little Malayan girl from the “Seven Seas” Club.

“Signal, sir!” The voice shattered his thoughts.

The young signalman waited respectfully while his superior collected his wits.

“Well?” The Malayan girl vanished.

“Government House, sir, just signalled to say that Mr. Gore-Lister an’ his assistant are comin’ over to see the Admiral.”

“Is that all?” His eyes scanned the brief flimsy.

“S’all, sir.”

He tugged his jacket straight, and started towards the screen-door.

“Oh, Quartermaster,” he snapped. “Two Government House men will be aboard shortly. Call me when you sight the launch!”

He stepped gingerly over the high coaming, cursing these damned civil servants who thought it necessary to do their business on a Sunday.

* * * * *

Vice-Admiral Sir Ralph Meadows tossed the signal carelessly on to his desk, and walked thoughtfully to the open scuttle overlooking the harbour. His pale, china-blue eyes surveyed the colourful panorama before him with apparent disinterest, but as usual, his quick brain was summing up all the possibilities for the unexpected visit from the representatives of Her Majesty’s Government.

He was a small man, built compactly and neatly. Everything about the Admiral was neat, from his thin, finely-cut features, burned to a nut-brown by his years of service overseas, to his narrow shoulders, and delicately shaped hands. Many people in the past had mistaken his fragile appearance for weakness, a mistake which had cost them a great deal, in their own comfort and security.

His eyes were perhaps the real clue to his true identity, cold and clear, yet giving the impression of his great insight and farseeing intelligence.

At that moment, he was thinking more of his past, than of what might happen when the new crisis arose.

He had started his service as a young midshipman right here, in China, helping to patrol the great trade routes on the Yangtse,

and trying to learn something about the vast, unfathomable peoples which thronged its banks. Pirates, dope smuggling, slavery, and minor wars had all made their mark on his young mind, and he had left the China Station with a true, if youthful regret. He had imagined that those experiences were to be the end of his contact with the country, but after a lifetime in other parts of the world, two world wars, and a steady climb up the uncertain ladder of promotion and appointment, he had returned, as Commander-in-Chief of the overworked Inshore Squadron.

And in a few more months, he would be leaving China, and the navy. This time for ever.

He watched the ferry steamer puffing past, the rows of faces upturned towards the British cruiser. He had changed a lot from the pink faced midshipman, but China, he shrugged inwardly, she was still about the same. Pirates and dope smugglers still abounded. The minor wars had been replaced by something bigger, but basically it was the same.

He turned slowly, and surveyed his spacious stateroom, which ran the whole breadth of the ship. The green fitted carpets, the polished brass scuttles, and immaculate white paintwork, all gave an appearance of security and well-being. A selection of bell buttons and telephones connected him with his minions and his command, and a word from him could make or break any one of them. He found it a vaguely comforting thought.