Sculptor's Daughter (3 page)

Read Sculptor's Daughter Online

Authors: Tove Jansson

B

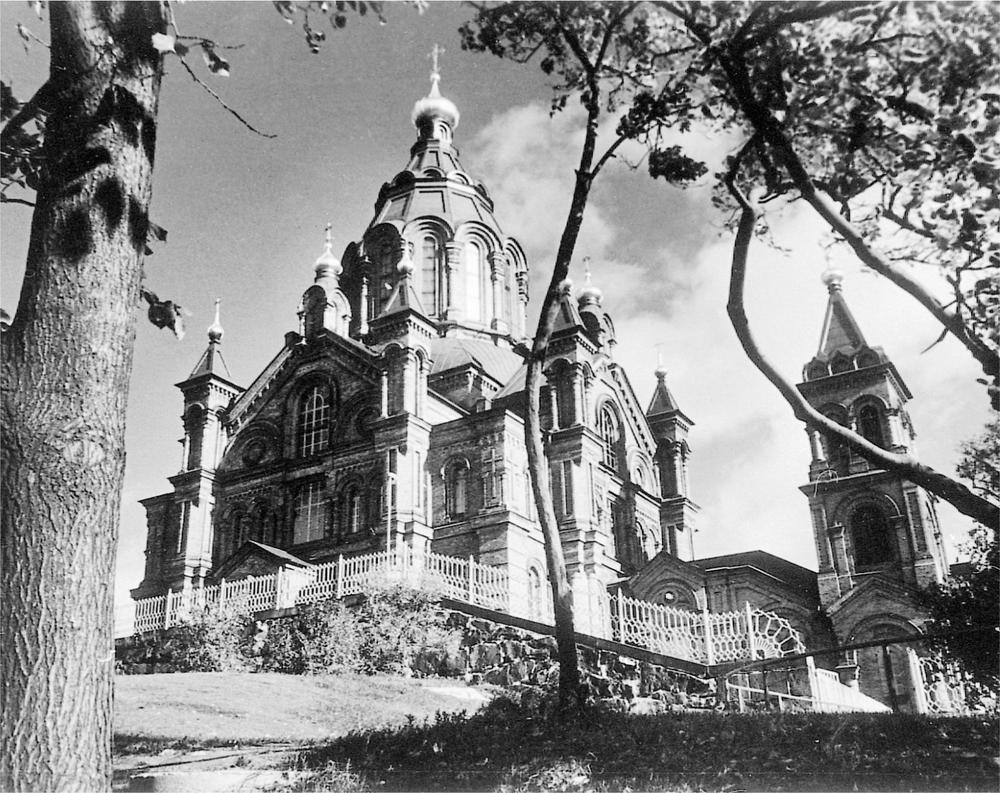

EHIND THE RUSSIAN CHURCH

there is an abyss. The moss and the rubbish are slippery and jagged old tins glitter at the bottom. For hundreds of years they have piled up higher and higher against a long dark red house without windows. The red house crawls round the rock and it is very significant that it has no windows. Behind the house is the harbour, a silent harbour with no boats in it. The little wooden door in the rock below the church is always locked.

Hold your breath when you run past it, I told Poyu. Otherwise Putrefaction will come out and catch you.

Poyu always has a cold. He can play the piano and holds his hands in front of him as if he were afraid of being attacked or was apologising to someone. I always scare him and he follows me because he wants to be scared.

As soon as twilight comes, a great big creature creeps over the harbour. It has no face but has got very distinct hands which cover one island after another as it creeps forward. When there are no more islands left it stretches its arm out over the water, a very long arm that trembles a little and begins to grope its way towards Skatudden. Its fingers reach the Russian Church and touch the rock â oh! Such a great big grey hand!

I know what it is that's the worst thing of all. It's the skating-rink. I have a six-sided skating badge sewn to my jumper. The key I use to tighten my skates is on a shoelace round my neck. When you go down onto the ice, the skating-rink looks like a little bracelet of light far out in the darkness. The harbour is an ocean of blue snow and loneliness and nasty fresh air.

Poyu doesn't skate because his ankles wobble, but I have to. Behind the rink lies the creeping creature and round the rink there is a ring of black water. The water breathes at the edge of the ice and moves gently, and sometimes it rises with a sigh and spreads out over the ice. When you are safely on the rink it isn't dangerous any more but you feel gloomy.

Hundreds of shadowy figures skate round and round, all in the same direction, resolutely and pointlessly, and two freezing old men sit playing in the middle under a tarpaulin. They are playing âRamona' and âI go out of an evening but my old girl stays at home'. It is cold. Your nose runs and when you wipe it you get icicles on your mittens.

Your skates have to be fixed to your heels. There's a little hole of iron and it's always full of small stones. I pick them out with the key of my skates. And then there are the stiff straps to thread through their holes. And then I go round with the others in order to get some fresh air and because the skating badge is very expensive. But there's no one here to scare, everybody just skates faster, strange shadows making scrunching and squeaking noises as they pass.

The lamps sway to and fro in the wind. If they went out we should keep going round and round in the dark, and the music would play on and on and gradually the channel in the ice would get wider and wider, yawning and breathing more heavily, and the whole harbour would be black water with only an island of ice on which we would go round and round for ever and ever amen.

Ramona is as pretty as a picture and as pale as The Thunder Bride. Ramona is for adults only. I have seen The Thunder Bride at the waxworks. Daddy and I love the waxworks. She was struck by lightning just when she was going to get married. The lightning struck her myrtle wreath and came out through her feet. That's why she is barefoot, and you can see quite clearly lots of crooked blue lines on the soles of her feet where the lightning came out again.

At the waxworks you can see how easy it is to smash people to pieces. They can be crushed, torn

in half or sawn into little bits. Nobody is safe and therefore it is terribly important to find a

hiding-place

in time.

I used to sing sad songs to Poyu. He put his hands over his ears but he listened all the same. Life is an isle of sorrow, you live today and die tomorrow! The skating-rink was the isle of sorrow. We drew it underneath the dining-room table. With a ruler Poyu drew every plank in the fence and the lamps all at the same distance from one another and his pencil was always too hard. I only drew black and with a 4B â the darkness on the ice, or the channel in the ice or a thousand murky figures on squeaking skates flying round in a circle. He didn't understand what I was drawing, so I took a red pencil and whispered: Marks of blood! Blood all over the ice! And Poyu screamed while I captured this cruel thing on paper so that it couldn't get at me.

One Sunday I taught Poyu how to escape from the snakes in their big carpet. All you have to do is walk along the light-coloured edges, on all the colours that are light. If you step on the dark colours next to them you are lost. There are such swarms of snakes there you just can't describe them, you have to imagine them. Everyone must imagine his own snakes because no one else's snakes can ever be as awful.

He balanced himself with tiny, tiny steps on the carpet, his hands in front of him and his great big wet handkerchief flapping in one hand.

Now it's getting narrow, I said. Look out for yourself and try to jump to that pale flower in the centre!

The flower was almost right behind him and the pattern disappeared in a twirl. He tried desperately to keep his balance, flapped his handkerchief and began to scream, and then fell into the dark part. He screamed and screamed and rolled over on the carpet, rolled off onto the floor and under a cupboard. I screamed too, crawled after him and put my arms round him and held him tight until he calmed down.

People shouldn't have pile carpets, they're dangerous. It's much better to live in a studio with a concrete floor. That's why Poyu is always longing to come to our place.

We are busy digging a secret tunnel through the wall. I've got quite a long way and I only work when I'm alone. The wooden panelling went all right but then I had to use the marble hammer. Poyu's hole is much smaller but his Daddy's tools are so bad that it's a disgrace.

Every time I'm alone I take down the hanging on the wall and dig away and no one has noticed what I am doing. The hanging is Mummy's. She painted it on sack-cloth when she was young. It shows an evening. There are straight tree-trunks rising out of the moss and behind the tree-trunks the sky is red because the sun is setting. Everything except the sky has gone dark in a vague greyish brown but there are narrow red streaks that burn like fire. I love her picture. It goes deep into the wall, deeper than my hole, deeper than Poyu's drawing-room, it goes on endlessly and one never gets to the place where the sun is setting but the red gets more and more intense. I'm sure it's burning! There is a terrible fire, the kind of fire Daddy is always going out and waiting for.

The first time Daddy showed me his fire it was winter. He went across the ice first and Mummy came behind him, pulling me on a sledge. It was the same red sky and the same shadowy figures running and something terrible had happened. There were jagged black things lying on the ice. Daddy collected them together and placed them in my lap, they were very heavy and pressed against my tummy.

Explosion is a beautiful word and a very big one. Later I learned others, the kind you can whisper only when you're alone. Inexorable. Ornamentation. Profile. Catastrophic. Electrical. District Nurse.

They get bigger and bigger if you say them over and over again. You whisper and whisper and let the word grow until nothing exists except the word.

I wonder why fires always happen at night. Perhaps Daddy isn't interested in fires during the daytime because then the sky isn't red. He always woke us up and we heard the fire engine clanging, there was always a great rush and we ran through completely empty streets. It was always an awful long way to Daddy's fires. All the houses

were asleep and the pointed chimneys were lifted upwards towards the red sky which got nearer and nearer and at last we got there and Daddy lifted me up to see the fire. But sometimes it was a silly little fire that had already gone out long before we got there and then he was disappointed and had to be consoled.

Mummy only likes little fires like the ones she makes in ashtrays when no one is looking. And log-fires. She lights log-fires in the studio and in the passage every evening after Daddy has gone out looking for his friends.

When the log-fire is alight we draw up the big chair. We turn out the lights in the studio and sit in front of the fire and she says: once upon a time there was a little girl who was terribly pretty and her mummy liked her so awfully much ⦠Every story has to begin in the same way, then it's not so important what happens. A soft, gentle voice in the warm darkness and one gazes into the fire and nothing is dangerous. Everything else is outside and can't get in. Not now or at any time.

My Mummy has lots of dark hair and it falls round you like a cloud, it smells nice and is like the hair of the sad queens in the book. The most beautiful picture covers a whole page. It shows a landscape at twilight, a plain covered with lilies. Pale queens are wandering over the whole plain with watering cans. The nearest one is indescribably beautiful. Her long dark hair is as soft as a cloud and the artist has covered it with sequins, probably some special finishing coat when the rest was done. Her profile is gentle and grave. And she walks there watering for the whole of her life and no one really knows how beautiful and how sad she is. The watering cans are painted with real silver and how the publisher could afford such a thing neither Mummy nor I can understand.

Mummy's stories are often about Moses â in the bulrushes and later; about Isaac and about people who are homesick for their own country or get lost and then find their way again; about Eve and the Serpent in Paradise and great storms that die away in the end. Most of the people are homesick anyway, and a little lonely, and they hide themselves in their hair and are turned into flowers. Sometimes they are turned into frogs and God keeps an eye on them the whole time and forgives them when he isn't angry and hurt and destroying whole cities because they believe in other gods.

Moses couldn't always control himself either. But the women just waited and longed for their homes. Oh I will lead you to your own country or to whatever country in the world you want and paint sequins in your hair and build a castle for you where we shall live until we die and never never leave each other. Through endless forest dark and drear no comfort near a little girl alone did roam so far from home the way was long the night was cold the thunder rolled the girl did weep no more

I'll find my mother kind for in this lonely haunted spot my awful lot will be beneath this tree to lie and slowly die.

Very satisfying. That's how it was when we shut the danger out.

Daddy's statues moved slowly round us in the light from the fire, his sad white ladies stepping warily, all ready to escape. They knew about the danger that lies in wait everywhere but nothing could save them until they were carved in marble and placed in a museum. There one is safe. In a museum or in a lap or in a tree. Perhaps under the bedclothes. But the best thing of all is to sit high up in a tree, that is if one isn't still inside one's Mummy's tummy.