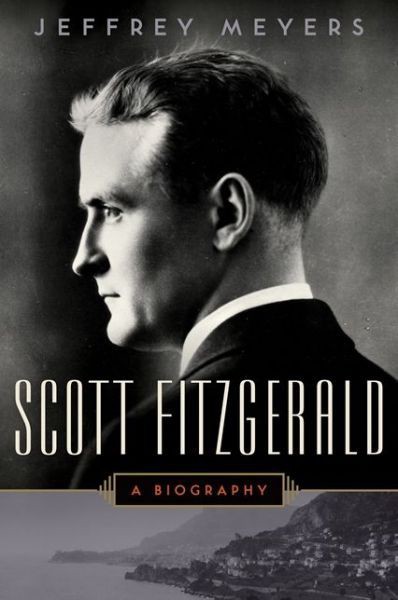

Scott Fitzgerald: A Biography

Read Scott Fitzgerald: A Biography Online

Authors: Jeffrey Meyers

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Nonfiction, #Retail

Scott Fitzgerald

A BIOGRAPHY

Jeffrey Meyers

For Valerie Hemingway

Fitzgerald is a subject no one has a right to mess up. Nothing but the best will do for him. I think he just missed being a great writer, and the reason is pretty obvious. If the poor guy was already an alcoholic in his college days, it’s a marvel that he did as well as he did. He had one of the rarest qualities in all literature. . . . The word is charm—charm as Keats would have used it. . . . It’s a kind of subdued magic, controlled and exquisite.

—Raymond Chandler

Contents

1. St. Paul and the Newman School, 1896–1913

3. The Army and Zelda, 1917–1919

4.

This Side of Paradise

and Marriage, 1920–1922

5.

The Beautiful and Damned

and Great Neck, 1922–1924

6. Europe and

The Great Gatsby,

1924–1925

7. Paris and Hemingway, 1925–1926

8. Ellerslie and France, 1927–1930

10. La Paix and

Tender Is the Night,

1932–1934

11. Asheville and “The Crack-Up,” 1935–1937

12. The Garden of Allah and Sheilah Graham, 1937–1938

13. Hollywood Hack and

The Last Tycoon,

1939–1940

Appendix I: Poe and Fitzgerald

Appendix III: The Quest for Bijou O’Conor

1. Edward Fitzgerald with Scott, Buffalo, Christmas 1899

3. Father Sigourney Fay, c.1917

8. Fitzgerald in Montana, 1915

12. Fitzgerald and Zelda, February 1921

13. Ring Lardner, Chicago, c.1910

17. Ernest Hemingway, Princeton, October 1931

18. Fitzgerald, Zelda and Scottie, Paris, Christmas 1925

20. Bijou O’Conor (

right

) with her father, Sir Francis Elliot, c.1925

21. Dr. Oscar Forel with his father, Auguste, and his son, Armand, c.1930

22. Fitzgerald and Zelda, Baltimore, 1932

23. Fitzgerald and Scottie, Baltimore, 1935

24. Irving Thalberg and Norma Shearer Thalberg, mid-1930s

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the assistance I received while writing this book. My friend Jackson Bryer encouraged and helped from the very beginning; and the University of California at Berkeley appointed me a Visiting Scholar. For interviews I would like to thank Sally Abeles-Gran, Ellen Barry, Helen Blackshear, Fanny Myers Brennan, Tony Buttitta, Alexander Clark, Honoria Murphy Donnelly, Virginia Foster Durr, Marie Jemison, Frances Turnbull Kidder, Eleanor Lanahan, Ring Lardner, Jr., Joseph Mankiewicz, Margaret Finney McPherson, Julian and Leslie McPhillips, Edgar Allan Poe III, Landon Ray, Frances Kroll Ring, Budd Schulberg, Courtney Sprague Vaughan and Hugh Wynne.

During my quest for Bijou O’Conor I also interviewed Sir Brinsley Ford, the Earl of Minto, Michael O’Conor, Gillian Plazzota and Sir William Young; and received letters from Frances Bebis, Anthony Blond, Claire Eaglestone of Balliol College, Margaret Elliot of the Elliot Clan Society, William Furlong, Francis King, Joyce Markham of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the Honourable Mary Alington Marten and the National Portrait Gallery, London.

During my search for Beatrice Dance I received help from Bond Davis, Helen Handley, Joan Sanger and Dan Laurence as well as from the Bexar County Courthouse, the Historical Society of San Antonio, the San Antonio Bar Association, the San Antonio Conservation Society and the San Antonio Public Library.

For other letters about Fitzgerald I am grateful to Sally Taylor Abeles, David Astor, Dr. Benjamin Baker, John Biggs III, Jonathan Bishop, Sarah Booth Conroy, Anthony Curtis, the Marquess of Donegall, Maureen, Marchioness of Donegal, Susan Mok Einarson, Armand Forel, Ian Hamilton, Valerie Hemingway, John Howell, Samuel Lanahan, Whitney Landon, Richard Lehan, Allan Margolies, Samuel Marx, Linda Miller, Dr. Paul Mok, David Page, Henry Dan Piper (who sent me the notes of interviews he conducted in the 1940s), Anthony Powell, Ruth Prigozy, Cecilia Lanahan Ross, Marie Sauer, Meryle Secrest, Henry Senber, Dodgie Shaffer, Robert Squier, Joan Kennedy Taylor, Rosalind Wilson, Archer Winsten and Roger Wunderlich.

I received useful information from the following institutions and libraries: the Alabama Department of Archives and History; the Archdiocese of Baltimore (Reverend Paul Thomas); the Association of Theatrical Press Agents and Managers; Bryn Mawr School, Baltimore; BBC Television (Jill Evans); the Lord Chamberlain’s Office, Buckingham Palace; Highland Hospital (Carol Anne Freeman); Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts; National Archives and Records Administration, St. Louis; the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.; National Sound Archive, London; Harold Ober Associates; Hôpital de Prangins; Public Broadcasting Service, Alexandria, Virginia; Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum, Montgomery, Alabama; the Embassy of Switzerland; and Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Hospital (Eleanor Barnhart). Also: the Firestone Library, Princeton University (the main collection of Fitzgerald’s papers); Catholic University of America; Cornell University; Harvard University; Southern Illinois University; the University of Alabama, Birmingham; the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa; the University of Cincinnati; the University of Delaware; the University of Pennsylvania; Stanford University and Yale University.

As always, my wife, Valerie Meyers, scrutinized each chapter.

The novelist Jay McInerney, writing in the

New York Review of Books

in August 1991, summarized the limitations of the previous biographies of Fitzgerald and mentioned “Bruccoli’s hagiographic

Some Sort of Epic Grandeur,”

Mellow’s peevish, sordid

Invented Lives,

as well as Scott Donaldson’s folksy psychoanalysis in

A Fool for Love . . .

Arthur Mizener’s excellent and grim

The Far Side of Paradise,

Andrew Turnbull’s biographical memoir

Scott Fitzgerald

and Nancy Milford’s feminist revisionist

Zelda.

What doesn’t emerge from any of these books is the sense of a coherent personality.” Fitzgerald himself pessimistically pointed out the difficulty of capturing the essence of a writer: “There never was a good biography of a good novelist. There couldn’t be. He’s too many people if he’s any good.”

Yet the romantic and tragic Fitzgerald, who seemed to embody the two decades between the wars, continues to fascinate and to inspire attempts to capture his elusive personality. Though I have profited in various ways from the earlier biographies, my book on Scott is more analytic and interpretive. It discusses the meaning as well as the events of his life and seeks to illuminate the recurrent patterns that reveal his inner self. This biography places much greater emphasis on Scott’s drinking; on Zelda’s hospitals and doctors, especially Oscar Forel and Robert Carroll; on his love affairs, before and after Zelda’s breakdown, with Lois Moran, Bijou O’Conor, Nora Flynn, Beatrice Dance and Sheilah Graham. It also focuses on his personal relations with his mentors at the Newman School, Father Fay (who was in love with Scott) and Shane Leslie; his Princeton friends, Edmund Wilson and John Peale Bishop; the humorist and screenwriter Donald Ogden Stewart; the polo star Tommy Hitchcock; the Hollywood executive Irving Thalberg; the journalist Michel Mok; and his daughter, Scottie, who wrote a great deal about him. I also say much more than I did in my 1985 biography of Hemingway about the most important literary friendship of the twentieth century.

St. Paul and the Newman School, 1896–1913

I

At the turn of the century St. Paul, Minnesota, where Scott Fitzgerald grew up, was a small Midwestern city with a genteel atmosphere and a highly stratified society. Scott’s parents, both Catholic and of Irish descent, came from very different social backgrounds. Even as a boy, he had a keenly developed sense of social nuance. He learned, from observing his odd, insecure parents, to worry about where his family belonged in “good” society. Fitzgerald’s novels portray the restless American middle and upper classes in the early decades of the century, and his fictional themes evolve from his origins in St. Paul. His young heroes are, like himself, fascinated by money and power, impressed by glamour and beauty. Yet they know they can never fully belong to this secure and prosperous world, that the goal of joining this careless, dominant class is an illusion.

In his

Notebooks

and his

Ledger

—a month-by-month account of his own life, which he began in 1919 and kept until 1936—Fitzgerald recorded all the details that would help him define exactly who he was and where he stood. He wanted not only to describe how he was shaped by his social background, but also to differentiate himself from it. In his

Notebooks

he later analyzed the social structure of St. Paul. Situated on a prairie and next to a great river, far from cultural centers, the city took its tone from the East and Europe rather than from Midwestern agriculture or the Mississippi river trade. At the head of the social hierarchy were the older established families who practiced the learned professions and considered themselves superior to the self-made businessmen and the obscure, Gatsby-like upstarts: “At the top came those whose grandparents had brought something with them from the East, a vestige of money and culture; then came the families of the big self-made merchants, the ‘old settlers’ of the sixties and seventies, American-English-Scotch, or German or Irish, looking down upon each other somewhat in the order named—upon the Irish less from religious difference—French Catholics were considered rather distinguished—than from the taint of political corruption in the East. After this came certain well-to-do ‘new people’—mysterious, out of a cloudy past, possibly unsound.” The upper class of this self-consciously snobbish society, which was based on “background,” good manners and the appearance of morality, lived on Summit Avenue. This elegant Victorian boulevard—filled with “turreted, spired, porticoed and cupolaed ‘palatial’ residences”—ran westward from the Catholic Cathedral of St. Paul to a bluff overlooking the commercial town and a bend of the Mississippi River.

The most imposing mansion on Summit Avenue belonged to the abstemious and laconic multimillionaire James J. Hill. Born in humble circumstances in Ontario, Canada, in 1838, he had made St. Paul the headquarters of his Great Northern Railway and fulfilled his pioneer’s dream by driving it across the Western wilderness to the Pacific coast. Hill, a financial ally of J. P. Morgan, was “a short, thick-set man, with a massive head, large features, long black hair, and a blind eye. . . . He had no small scruples [and was] rough-hewn throughout, intolerant of opposition, despotic, largely ruling by fear.”

1

No man did more for St. Paul, as exemplar and benefactor, than this empire builder and railroad magnate.

Scott’s Aunt Annabel McQuillan had been maid of honor at the wedding of Hill’s daughter. In boyhood he was fascinated by the fabulous wealth and influence of this legendary figure, who inspired Fitzgerald’s imagination and frequently appeared in his fiction. In his first novel,

This Side of Paradise

(1920), the hero, Amory Blaine, speaking of the futile attempt to make business interesting in fiction, remarks: “Nobody wants to read about it, unless it’s crooked business. If it was an entertaining subject they’d buy the life of James J. Hill.” Later on, when advocating government ownership of industry during an argument with the rich father of his Princeton friend, Amory states: “we’d have the best analytical minds in the government working for something besides themselves. We’d have . . . Hill running interstate commerce.”