Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985-2010 (50 page)

Read Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985-2010 Online

Authors: Damien Broderick,Paul di Filippo

TRUE GENIUS

in crafting a runaway pop sensation, as many critics have noted, lies in providing “familiar novelty.” In other words, supplying the reading or viewing or listening public with something easily identifiable and likable, something readily apprehendable, something they have enjoyed in the past, yet with just enough difference to render the product fresh and unique, quivering excitingly at the tip of the zeitgeist. But of course, that’s just the conceptualizing portion of the creator’s job. The heavy lifting involved in reifying the concept; getting musical notes or words down on paper, or images on film, involves skill and craft and dogged dedication—not only in the composition, but in the marketing—as well as a firm belief in the integrity, value and organic unity of one’s vision.

J. K. Rowling is the biggest success story of this type in the field of fantastical literature. Her Potter-verse had numerous literary precedents, yet she was able to blend and tweak her selection of component parts into a stimulating new recipe, delivered with panache and zest. Rowling’s counterpart on the Young Adult sf front is surely Suzanne Collins, whose

Hunger Games

trilogy renders all the excitement, thrills, and thought-provoking controversies of past great sf novels, incarnated by a stellar cast of characters with whom readers can easily empathize.

It’s easy enough to itemize the parts that went into Collins’s trilogy. The Japanese cross-platform sensation

Battle Royale

. William Golding’s

Lord of the Flies

. Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery.” Fredric Brown’s “Arena.” Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game.” Robert Sheckley’s The 10th Victim. Heinlein’s Tunnel in the Sky. A bit of Baum’s Oz (teenage girl stranded in a strange kingdom, and set an almost-impossible task before she can return home). Any number of post-apocalypse, “world made by hand” dystopias, from Wells on down. And, paramount, the reality-TV series Survivor. But such a cold-blooded dissector’s catalogue fails to capture the sheer reading pleasure, emotional impact and polished presentation of Collins’s saga.

A century or so beyond the present day, the shards of the collapsed United States of America have been reconstituted into a dictatorial ruling city, Capitol, set in the Rockies and surrounded by twelve oppressed Districts that pay tribute with young warriors who must compete in the mortality-rife bread-and-circuses Hunger Games. Our heroine is Katniss Everdeen, who makes the Christ-like gesture of submitting her exempted self to the Games in her younger sister’s place. Once in Capitol she is subject to cynical media grooming (resonance with the hypermedia decadence of Jodorowsky’s graphic novel

Incal

spring to mind) almost worse than the combat to come.

But that combat does come, and is unsparingly conveyed. Here’s the aftermath of Kat killing another girl by exposing her to mutant wasps.

The girl, so breathtakingly beautiful in her golden dress the night of the interviews, is unrecognizable. Her features eradicated, her limbs three times their normal size. The stinger lumps have begun to explode, spewing putrid green liquid around her.

Needing the dead girl’s bow and arrows, Kat has to manhandle this human wreckage to get them.

After surviving the Games with her village-mate Peeta, Kat finds, in

Catching Fire

, that the deadliest days have just begun. The suicidal act of defiance that won her and Peeta an unprecedented shared victory, telecast to the nation, has brought long-quashed rebellion to a simmer.

Back in District 12, and touring the country, Kat finds herself—under the symbol of the mockingjay pin she famously wears—reluctantly at the heart of the turmoil, while concerned simultaneously with keeping her loved ones alive, and with burgeoning parallel romances with Peeta and old hunter friend Gale. But then comes an unexpected return to the savage arena, and with it another literary influence rears its head. The clock-shaped technological booby-trap, where Kat and crew rumble, summons up nothing so much as the gloriously insane, over-planned traps the Joker used to engineer for the Silver Age Batman. But on a weightier level, clever allusions to the Mitteleuropean revolts of 1989 and even prescient temblors from the Arab Spring vibrate through this portion of the saga as well.

Collins’s charming first-person voice for Kat continues unerringly, pulling the reader deep into the action, and the increasingly mature and realpolitik-savvy girl of this installment is a realistic expansion of the young woman who entered the Games all naïve.

Collins unrelentingly ratchets up the stakes and tensions in the concluding volume,

Mockingjay

, which shifts to the venue of District 13, the legendary rebel redoubt that proves, distressingly, to be literally underground, a militarized autocracy on the lines of George Lucas’s THX 1138 or Philip K. Dick’s The Penultimate Truth. Kat is forced into the Joan of Arc role of Mockingjay, and also acquires a bit of a superhero patina, what with her intelligent weapons and armor. Romantic concerns serve as welcome interstitial moments, with Gale by her side, yet emotionally distant, and Peeta a tortured captive in the Capitol. The savagery of the arena, naturally missing, is replaced by the brutality of combat, culminating in Katniss’s squad-level, then solo, assault on the Capitol, in the manner of a John Scalzi or David Drake military novel. The ultimate ending: Orwellian victory, betrayals, sacrifice, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and a harsh grace.

The success of Rowling and Collins, as well as Stephanie Meyer and a host of second-tier YA authors, among both their intended adolescent audience and a huge number of adult readers, raises the provocative question of whether “mature” science fiction has reached a point of self-referential, inward-looking decadence that has contributed to the dwindling of its readership. (A similar instance in the field of comics draws parallels with the senescent output of DC and Marvel, and a charming yet callow rogue like

Scott Pilgrim

.) Certainly,

The Hunger Games

provides more immediate surface pleasures and points of newbie access than

The Quantum Thief

(Entry 101). But sacrificing the accumulated thick intertextual continuity of a century’s worth of adult science fiction might not be strictly necessary for the genre’s survival, if we can interbreed the best YA sf with the best adult sf, selecting for the virtues that appeal to the eternal thirteen-year-old, sense-of-wonder addict in us all.

94

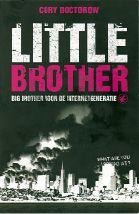

Cory Doctorow

(2008)

WHILE THE MAJORITY

of his science-fictional peers forsake the genre’s historical commitment to near-term speculations and politically conscious fiction, fleeing for the bland safety of Middle Earth or Wizard School or Interstellar Empires, Cory Doctorow plunges headlong into the venerable tradition of admonitory, near-future prophecy. He’s a smart and talented and inventive writer, still as youthful and energetic and optimistic, despite approaching age forty, as he was upon his precocious debut in 1998. His ability to function on the bleeding edge of technology and culture is daily exhibited by his partnered curatorship of one of the web’s most popular and influential blogs,

Boing Boing

. All of these qualities are evident from page one of

Little Brother

, latest in a long line of anti-authoritarian books.

Ever since Anthony “Buck” Rogers sought to overthrow America’s evil Han overlords in the pages of his 1928

Amazing Stories

debut, “Armageddon 2419 A.D.,” science fiction has concerned itself with prophecies of doom for the United States and its unique and transcendental form of democracy. (This hortatory mode actually began in England, all the way back in 1871, with George Chesney’s

The Battle of Dorking

, a work that sparked scores of other John-Bull-endangered scenarios.) Almost immediately thereafter, writers as diverse and as diversely talented as John W. Campbell, Robert Heinlein, Fritz Leiber and Jerry Sohl took up the gauntlet, depicting Old Glory besmirched under the thumb of forces inimical to our revered core values. By 1962, the format had reached some kind of mad apotheosis and larger cultural significance and awareness with the release of the fictionalized documentary Red Nightmare, in which narrator Jack Webb was our Virgil on a journey across a hellish USA overrun with Commies.

At the same time, a second literary strain foresaw the possibility of decay and dictatorship from within: homegrown worms burrowing within our own subverted institutions. Sinclair Lewis conjured up a nativist presidential dictator in

It Can’t Happen Here

. And of course Orwell’s

Nineteen Eighty-four

implicitly limned a dystopia that had sprouted stepwise over time on domestic soil, rather than being imposed from without by foreigners. This sense of a democracy betrayed by factions within that had lost sight of its seminal values naturally received a huge boost in the 1960s, reflecting the prevalent mistrust of government. A late-period instance of this formulation is the graphic novel by Alan Moore,

V for Vendetta

(1982-88, and filmed in 2006).

Both types of science fiction—and their hybrid offspring—lend themselves to certain shared plot devices, a stew of motifs from the American Revolution, the French Resistance, and other historical rebellions. A simmering revolt against seemingly impossible odds, led by a charismatic hero of the underground and his loyal posse, including one or more babelicious fellow female freedom fighters. Treachery, sacrifice, atrocities, temporary defeats and ultimate victories. Noble speeches, cruel dictates, torture and resistance. Often, the rebels will enlist or invent new technology to aid their cause, explicitly endorsing America’s Edisonian virtues and privileging the small, idealistic and flexible forces over the ossified, cynical, superior powers.

Such stories are among the most stirring and topical and edifying sf novels ever written. As has been famously argued, Orwell’s book alone probably forestalled the very future it so convincingly painted as inevitable. But of course, such a potent toolbox works perfectly well for any ideology, no matter how dangerous and despicable. William Luther Pierce’s reprehensibly racist

The Turner Diaries

is the black sheep of this genre, but no less powerful for that.Doctorow’s

Little Brother

is a book which fits as perfectly into this tradition as if organically grown from the seeds of its predecessors. Luckily, Doctorow and his novel are on the side of the angels, i.e., America’s Founding Fathers and a contemporary citizenry that’s proud, thoughtful, and knows the true meaning of patriotism.

Little Brother

is the first-person tale of Marcus Yallow, a seventeen-year-old student in San Francisco on the day after tomorrow. (The ineluctable presence of a teen narrator and the publisher’s marketing have cast this book as a Young Adult title, and in fact it debuted on

The New York Times

Bestseller List, Children’s Chapter-book Division, at the number 9 slot. But all those who have enjoyed Doctorow’s past “adult” novels will find this an equally strong and mature and polished link in that chain.)

Marcus is a Good Boy and a Nice Kid from a fine middle-class liberal home, despite exhibiting the familiar adolescent impulses to mess around and goof off in harmless fashion. He also happens to be a cyberwhiz. One day he and some pals are bunking school. Unfortunately, this is the moment when al-Qaeda chooses to blow up the Bay Area Bridge and the underwater BART tunnels. In the chaos, Marcus and his pals are hauled off the streets in a military sweep and remanded to extra-legal inquisitors. After some harrowing physical and mental harassment based on his rebellious attitude and past misdemeanors, Marcus is eventually deemed a non-threat and turned loose.

But he discovers upon his return home that in the face of this terrorist assault America is well on its way to becoming an anti-privacy police state, with the Department of Homeland Security monitoring the travel, purchases and thinking of innocent citizens. Angry both at his own treatment and the general shrinking of freedoms, Marcus begins to lead a teenaged resistance movement.