Schild's Ladder (6 page)

Authors: Greg Egan

“I don't know how to help you make peace with that,” Rainzi said. “But I can only think of one way to make my own peace with the people we've endangered.” Mimosa was remote from the rest of civilization, but the process they'd begun would not burn itself out, would not fade or weaken with distance. With vacuum as its fuel, the wildfire would spread inexorably: to Viro, to Maeder, to a thousand other worlds. To Earth.

Cass asked numbly, “How?”

“If we can see a way to stop this,” Rainzi replied, “then it doesn't matter that we can't enact it ourselves, or even get the word out to anyone else. We can still take comfort in uncovering the right strategy. I know we have certain advantages—in the time resolution with which we're seeing the data, and in being the only witnesses to this early stage—but on balance, I think the combined population of the rest of the galaxy constitutes more than an even match. If we can find a solution, someone out there will find it, too.”

Cass looked around at the others. She felt lost, rootless. Not guilty, yet. Not monstrous. The Mimosans would all wake on Viro, missing a few hours' memories but otherwise unscathed, and though she'd robbed them of their home, they'd understood the risks as well as she did when they'd chosen to conduct the experiment. But if the loss of the Quietener and the station was something she could come to terms with, it was still surreal to extrapolate from her own few picoseconds of helplessness to the exile of whole civilizations. She had to face the truth, but she was far from certain that the right way to do that was to hunt for a solution that would at best be a plausible daydream.

Darsono caught her eye. “I agree with Rainzi,” he said solemnly. “We have to do this. We have to find the cure.”

“Livia?”

“Absolutely.” Livia smiled. “Actually, I'm far more ambitious than Rainzi. I'm not willing to concede yet that we can't stop this ourselves.”

Zulkifli said dryly, “I doubt that. But I want to know if my family will be safe.”

Ilene nodded. “It's not much, but it's better than giving up. I'm not bailing out just to spare myself the sense of being powerless—not while data's pouring in, and we can still look for an answer.”

“The danger doesn't seem real to me,” Yann admitted. “Viro is seventeen light-years away, and we can't be sure that this thing won't snuff itself out before it even grazes the shell of the Quietener. But I would like to know the general law that replaces the Sarumpaet rules. It's been twenty thousand years! It's about time we had some new physics.”

Cass turned to Bakim.

He shrugged. “What else are we going to do? Play charades?”

Cass was outnumbered, and she wanted to be swayed. She ached to get her hands on even the smallest piece of evidence that the disaster could be contained, and if they failed, it would still be the least morbid way to go out: struggling to the end to find a genuine cause for optimism.

But they were fooling themselves. In the few subjective minutes left to them, what hope did they have of achieving that?

She said simply, “We'll never make it. We'll test one hunch against the data, find it's wrong, and that will be it.”

Rainzi smiled as if she'd said something comically naive. Before he spoke, Cass recalled what it was she had forgotten.

What it was she had become.

He said, “That's how it will seem for most of us. But that shouldn't be disheartening. Because every time we fail, we'll know that another version of ourselves will have tested another idea. There will always be a chance that one of them was right.”

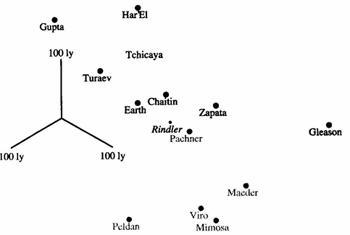

Inhabited Space

Only a small proportion of all

systems are shown. Shaded systems

have been lost behind the border

as Tchicaya arrives on the

Rindler

,

605 years after Mimosa.

By choice, Tchicaya's mind started running long before his new body was fully customized. As his vision came into focus, he turned his gaze from the softly lit lid of the crib to the waxen, pudgy template that he now inhabited. Waves of organizers swarmed up and down his limbs and torso like mobile bruises beneath the translucent skin, killing off unwanted cells and cannibalizing them, stimulating others to migrate or divide. The process wasn't painful—at worst it tickled, and it was even sporadically sexy—but Tchicaya felt an odd compulsion to start pummeling the things with his fists, and he had no doubt that squashing them flat would be enormously satisfying. The urge was probably an innate response to Earthly parasites, a misplaced instinct that his ancestors hadn't got around to editing out. Or perhaps they'd retained it deliberately, in the hope that it might yet turn out to be useful elsewhere.

As he raised his head to get a better view, he caught sight of an undigested stretch of calf, still bearing traces of the last inhabitant's body hair and musculature. “Urrggh.”. The noise sounded alien, and left a knot in his throat. The crib said, “Please don't try to talk yet.” The organizers swept over the offending remnant and dissolved it.

Morphogenesis from scratch, from a single cell, couldn't be achieved in less than three months. This borrowed body wouldn't even have the DNA he'd been born with, but it had been designed to be easy to regress and sculpt into a fair approximation of anyone who'd remained reasonably close to their human ancestors, and the process could be completed in about three hours. When traveling this way, Tchicaya usually elected to become conscious only for the final fitting: the tweaking of his mental body maps to accommodate all the minor differences that were too much of a nuisance to eliminate physically. But he'd decided that for once he'd wake early, and experience as much as he could.

He watched his arms and fingers lengthen slightly, the flesh growing too far in places, then dying back. Organizers flowed into his mouth, re-forming his gums, nudging his teeth into new locations, thickening his tongue, then sloughing off whole layers of excess tissue. He tried not to gag.

“Dith ith horrible,” he complained.

“Just imagine what it would be like if your brain was flesh, too,” the crib responded. “All those neural pathways being grown and hacked away—like a topiary full of tableaux from someone else's life being shaped into a portrait of your own past. You'd be having nightmares, hallucinations, flashbacks from the last user's memories.”

The crib wasn't sentient, but pondering its reply made a useful distraction from the squirming sensation Tchicaya was beginning to feel in his gut. It was a much more productive rejoinder than: “You're the idiot who asked to be awake for this, so why don't you shut up and make the best of it?”

When his tongue felt serviceably de-slimed, he said, “Some people think the same kind of thing happens digitally. Every time you reconfigure a Qusp to run someone new, the mere act of loading the program generates experiences, long before you formally start it running.”

“Oh, I'm sure it does,” the crib conceded cheerfully. “But the nature of the process guarantees that you never remember any of it.”

When Tchicaya was able to stand, the crib opened its lid and had him pace the recovery room. He stretched his arms, swiveled his head, bent and arched his spine, while the crib advised his Qusp on the changes it would have to make in order to bring his expectations for kinesthetic feedback and response times into line with reality. In a week or two he would have accommodated to the differences anyway, but the sooner they were dealt with, the sooner he'd lose the distracting sense that his own flesh was like poorly fitted clothing.

The clothes that were waiting for him had already been informed of his measurements, and the styles, colors, and textures he preferred. They'd come up with a design in magenta and yellow that looked sunny without being garish, and he felt no need to ask for changes, or to view a range of alternatives.

As he dressed, Tchicaya examined himself in the wall mirror. From the whorl of dark bristles on his scalp to the glistening scar running down his right leg, every visible feature had been reproduced faithfully from a micrometer-level description of his body on the day he'd left his home world. For all he could tell, this might as well have been the original. The internal sense of familiarity was convincing, too; he'd lost the slight tension in his shoulder muscles that had been building up over the last few weeks before his departure, but having just rid himself of all the far more uncomfortable kinks he'd acquired in the crib, that was hardly surprising. And if this scar was not the scar from his childhood, not the same collagen laid down by the healing skin in his twelve-year-old body, nor would it have been the same in his adult body by now, if he'd never left home. All an organism could do from day to day was shore itself up in some rough semblance of its previous condition. The same was true, from moment to moment, for the state of the whole universe. By one means or another, everyone was an imperfect imitation of whatever they'd been the day before.

Still, it was only when you traveled that you needed to dispose of your own past, or leave behind an ever-growing residue. Tchicaya told the crib, “Recycle number ten.” He'd forgotten exactly where the tenth-last body he'd inhabited was stored, but when his authorization reached it, the memories sitting passively in its Qusp would be erased, and its flesh would be recycled into the same kind of waxen template as the one he'd just claimed as his own.

The crib said, “There is no number ten, by my count. Do you want to recycle number nine?”

Tchicaya opened his mouth to protest, then realized that he'd spoken out of habit. When he'd left Pachner, thirty years before—a few subjective hours ago—he'd known full well that his body trail would be growing shorter by one while he was still in transit, and he wouldn't have to lift a finger or say a word to make it happen.

He said, “Keep number nine.”

As he stepped out of the recovery room, Tchicaya was grateful for his freshly retuned sense of balance. The deck beneath his feet was opaque, but it sat inside a transparent bubble a hundred meters wide, swinging for the sake of gravity at the end of a kilometer-long tether. To his left, the ship's spin was clearly visible against the backdrop of stars, all the more so because the axis of rotation coincided with the direction of travel. The stars turning slowly in the smallest circles were tinted icy blue, while away from the artificial celestial pole they took on more normal hues, ultimately reddening slightly. The right half of the sky was starless, filled instead with a uniform glow that was untouched by the Doppler shift, and so featureless that there was nothing to be seen moving within it: not one speck of greater or lesser brightness rising over the deck in time with the stars.

From the surface of Pachner, the border of the Mimosa vacuum had appeared very different, a shimmering sphere of light blazing a fierce steely blue at the center, but cooled toward the edges by its own varied Doppler shift. The graded color had made it look distinctly rounded and three-dimensional, and the fact that you could apparently see it curving away from you had added to an already deceptive impression of distance. Because it was expanding at half the speed of light, the amount of sky the border blotted out was not a reliable measure of its proximity. Looking away from its nearest point meant looking back to a time when it had been considerably smaller, and starlight that had grazed the sphere centuries before—skirting the danger, and appearing to delineate it—actually told you nothing about its present size. When Tchicaya had left, Pachner had been little more than two years away from being engulfed, but the border had barely changed its appearance in the decade he'd spent there, and it would still have occupied a mere one hundred and twenty degrees of the view at the instant the planet was swallowed.

Tchicaya had been on Pachner to talk to people on the verge of making their escape. He'd had to flee long before the hard cases, who'd boasted that they'd be leaving with just seconds to spare, but as far as he knew he'd been the only evacuee who was planning to end up closer to the border than when he left. Doomed planets were useless as observation posts; no sooner did the object of interest come near than you had to retreat from it at the speed of light. The

Rindler

was constantly retreating, but no faster than was absolutely necessary. Matching velocities with the border transformed its appearance; from the observation deck, the celestial image that had become an emblem of danger for ten thousand civilizations was nowhere to be seen. The border finally looked like the thing it was: a vast, structureless, immaterial wall between two incomparably different worlds.

“Tchicaya!”

He looked around. There were a dozen people nearby, but they were all intent on the view. Then he spotted a lanky figure approaching, an arm stretched up in greeting. Tchicaya didn't recognize the face, but his Mediator picked up a familiar signature.

“Yann?” Tchicaya had known for centuries that Yann was also weaving his way toward the

Rindler

, but the last place he'd expected to run into him was the observation deck. In all the time they'd been in contact, exchanging messengers across decades and light-years, Yann had been strictly acorporeal.