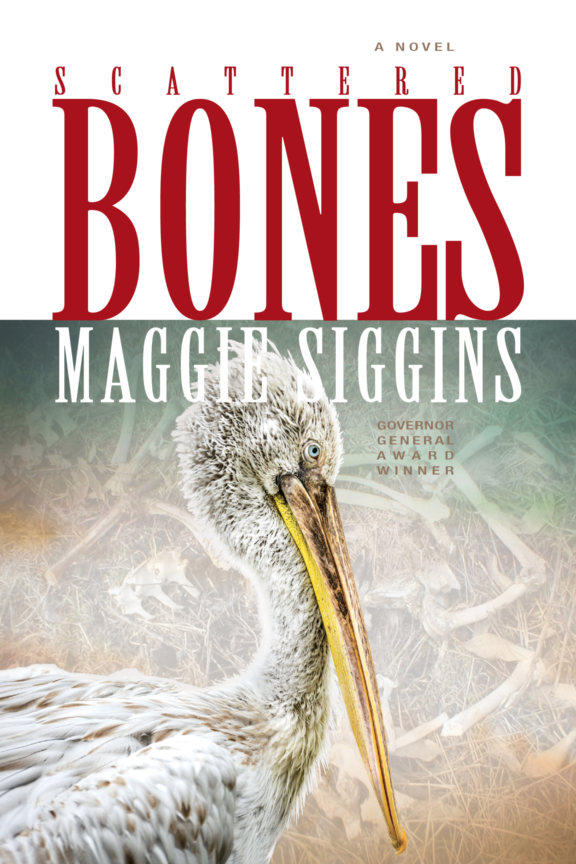

Scattered Bones

Authors: Maggie Siggins

Tags: #conflict, #Award-winning, #First Nations, #Pelican Narrows, #history, #settlers, #residential school, #community, #religion, #burial ground

- Book & Copyright Information

- Dedication

- Prologue

- THE ARRIVAL

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- ARTHUR JAN'S WELCOMING PARTY

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- THE CHILDREN'S PICNIC

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- REVEREND WENTWORTH'S SUMMIT

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- LUCRETIA WENTWORTH'S SOIRÃE

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twenty-One

- FATHER BONNALD'S TEA PARTY

- Chapter Twenty-Two

- Chapter Twenty-Three

- Chapter Twenty-Four

- Chapter Twenty-Five

- Chapter Twenty-Six

- Chapter Twenty-Seven

- Chapter Twenty-Eight

- THE DANCE

- Chapter Twenty-Nine

- JOE'S CONFESSION

- Chapter Thirty

- Chapter Thirty-One

- Chapter Thirty-Two

- Chapter Thirty-Three

- FLORENCE'S FAREWELL BREAKFAST

- Chapter Thirty-Four

- Chapter Thirty-Five

- Chapter Thirty-Six

- Chapter Thirty-Seven

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

© Maggie Siggins, 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access

Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll-free to 1-800-893-5777.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Edited by Dave Margoshes

Book designed by Scott Hunter

Typeset by Susan Buck

Printed and bound in Canada

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Siggins, Maggie, 1942-, author

Scattered bones / Maggie Siggins.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-55050-669-3 (paperback).--ISBN 978-1-55050-670-9

(pdf).--ISBN 978-1-55050-671-6 (epub).--ISBN 978-1-55050-672-3

(mobi)

I. Title.

PS8637.I286S28 2016 C813'.6 C2015-908767-8

C2015-908768-6

Available in Canada from:

Coteau Books

2517 Victoria

Avenue

Regina, Saskatchewan

Canada

S4P 0T2

www.coteaubooks.com

Coteau Books gratefully acknowledges the finan

cial support of its publishing program by: the Saskatchewan Arts Board, The Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Saskatchewan through Creative Saskatchewan, the City of Regina. We further acknowledge the [financial] support of the Government of Canada. Nous reconnaissons l'appui [financier] du gouvernement du Canada.

For my friends at Pelican Narrows

Prologue

Summer, 1730

A scorcher of a day.

So hot that when you sat on the rocks your bum got burnt. The insects, though, loved the heat. Auntie patted smudge all over our bodies, but the mosquitoes still nipped and the deer flies bit deep, until our blood mixed with the dust and turned into mud the colour of rust.

We girls picked berries – the tart reds, the sweet purples, the sour russets, the big blacks. We laughed our heads off when the juice of the Dewberries shot into the eyes of our cousins. “Maci-manchosis,

little devil,” Auntie laughed as she grabbed my youngest brother, the naughtiest of us all, and tickled him until he pleaded for mercy.

Still, even in our glee, we felt the unease that was pricking at our camp. Our mother was nervous and cross. Not a hint of a smile on her usually sunny face. We assumed she was upset because our father was absent.

Each summer the men of our band of Asiniskaw-itiniwak, Rock Cree, loaded their canoes so high we were sure they would sink. After they waved goodbye, they travelled along the great river to Fort Prince William where white peddlers were waiting to greet them. There, the skins of silver and red fox, otter, mink, marten, fisher and, most important, the thick, glossy, black/brown beaver were traded for European tools, guns and ammunition.

Since the trip lasted many moons, our mother would goad our father, insisting he relished the break from his noisy children and nagging wife. But she loved the things he brought back – the sturdy needles, scissors and knives made of iron, the copper kettles, the glass beads which she used to decorate moccasins, bags, and belts. Once, the cargo contained a round glass mirror. Mother had laughed out loud. Reflected there were the deep dimples in her cheeks. How often had she been teased about those! And the tattoos her sister had painted with such precision, two straight white lines drawn on an angle from the corner of her mouth to her lower jaw. These she had especially admired.

Father and the other men were expected back any day, and we thought Mother might be stewing about this. Anything could have gone wrong: violent lightning could stab a canoe – in a wink all would be drowned; savage forest fires could suddenly ignite – all campers burned to a crisp; and, most menacing, a chance meeting with their long-time enemy, the Sioux. Now mercenaries who worked for the French, the Sioux were paid well – guns, ammunition, rum, tobacco, anything they wanted – to eliminate anyone doing business with the British, the Asiniskaw-itiniwak included. But it turned out that father’s imminent return was not the reason for mother’s distress.

Two elders, Nanahewepathis and Chachake, both noted medicine men with strong shamanistic powers, had been left in charge of our summer camp, although as mother said, Chachake was so old and fragile, he would provide as much protection as the pelican he was named after. Each chief was responsible for half of the sixty lodges which sat along the sandy, half-moon beach of Pelican Lake and scattered up the hill behind it. Nanahewepathis was our mosom, my mother’s father, so naturally we were under his charge. Even in old age, he was a handsome man. His hair – black still, though speckled with white – was as thick as ever, braided into three plaits, two smaller ones falling at his ears and one down his back as thick as a moose’s thigh bone. This was his pride and joy, his vanity. Mother spent hours applying bear grease to make sure it shone.

Chachake, on the other hand, was scrawny with a beak-like nose that resembled the beak of the bird that was his namesake. He was always forecasting disaster and searching for signs to back up his gloomy predictions – a red-winged blackbird lying dead on the ground meant nothing, but, according to him, two such corpses discovered on the same day signalled a winter so severe starvation was sure to follow. He got on our mother’s nerves. “If the sun is shining, he will talk about the rain that is sure to fall. If it’s raining, he will remember how it snowed last year.”

That morning, very early, Chachake had banged on his drum and told everyone to gather round. His pawachi-kan – his guiding spirit – had visited him during the night and warned him that disaster was about to befall us. What the danger was, specifically, the spirit wouldn’t say, but it would be calamitous. We must pack up and move that very day.

Since we were just settled in after months of winter travel, this would be a huge undertaking, and besides, the men were expected soon, maybe even the next day. How would they find us? So we asked what Nanahewepathis had to say about this. He shook his big head. No such dark scenario had visited his sleep and surely, if Chachake’s dire warning was true, his pawachi-kan, his dream helper, would definitely have come to him as well. After all, his guardian spirit was cleverer and stronger than Chachake’s.

The arguments volleyed back and forth. The two old men were respectful and courteous to each other, and, when the discussion did heat up, a resolution was quickly found. Chachake’s entourage would relocate, Nanahewepathis’s people, my family included, would stay put.

Later in the afternoon I strolled over to say goodbye to my favourite cousin, Wapun, a girl born at the exact time I was and lucky because of that. The celebration of our first blood-flow had just been held. Wapun’s family had already dismantled their wigwam, the thin birch bark covering carefully removed, the long poplar poles taken down. These had been loaded in canoes, but most of their other paraphernalia – the silky bear-skin-covered eiderdown quilts, the pots, the kettles, the racks used to dry moose meat, the wooden cache where fish and other foods were stored – would be left behind. As soon as Chachake’s pawachi-kan signalled that the danger was gone, his people would return. Wapun and I hugged each other goodbye, but we weren’t too sad. We would be seeing each other soon.

Sitting around our fire that evening, we youngsters were eager to talk about the curious events of the day, but the stern and yet strangely nonchalant demeanour of our mosom signalled to us to keep quiet. Mother was more upset than I, the eldest of her four children, had ever remembered seeing her.

Recently, Mosom had taken special notice of me, his “cheerful blackbird.” I was assigned to sleep in his wigwam and do his fetching –

in particular to make sure that his wikis, dried rat root, was at hand when his rheumatism bothered him. “Soon a tall boy will take you away from us and then I will become a great grandfather," he said as he smiled at me.

“I will never leave you, my beloved mosom,” I had answered, although I knew this wasn’t true. I already had my eye on a certain beautiful boy.

That night, curled in my caribou bag, I fell into my usual deep sleep. As the first grey light appeared, I thought I heard a weird noise, a kind of deep-throated chant. It quickly ceased, and, thinking it was a dream, I fell back to sleep. A short time later I awoke to the terror that haunts me still, even now that my hair is white.

Standing in the middle of the wigwam was a tall, muscular man. Dark raven feathers shot out at the back of his head, green eagle feathers fell down his shoulders. His face was hideously decorated with black and white war paint, a whirl of blood red exploding on his forehead. A necklace of bones circled his neck. A leather loin cloth covered his private parts although I saw that enormous, telltale bulge protruding beneath it. In his raised hand he carried a curved metal knife. In a single, rapid motion, he grabbed my still-sleeping mosom by his hair, pulled his head back, and slit his throat.

Even now as I tell this story to you my beloved grandchildren, I still hear the dogs braying, the terrible human howls, the piteous pleading, the gun shots. A shadowy memory remains: of being roughly pushed from behind, of slipping in blood, of stumbling over mutilated bodies, young and old, babies even, all family of mine.

I was bundled into a canoe with the only other captive they took, a boy cousin about four years old, probably a replacement for a dead child of one of the chiefs. I put my arms around him, comforting him, trying so hard not to cry myself, not to throw up, not to faint.