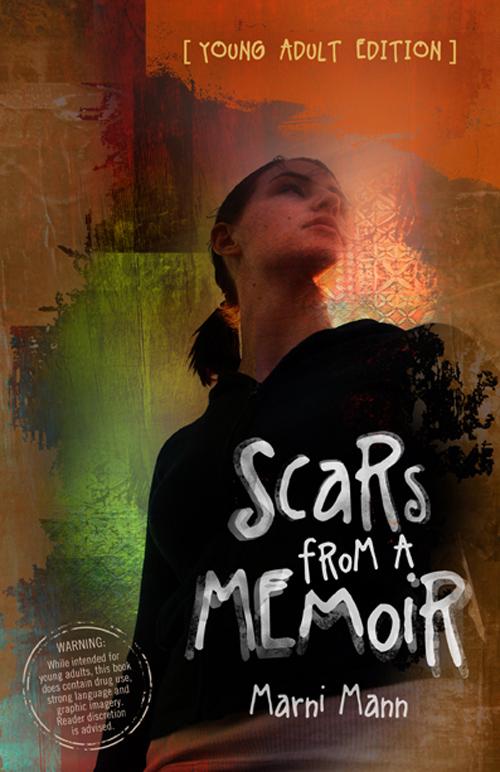

Scars from a Memoir

Read Scars from a Memoir Online

Authors: Marni Mann

Copyright 2012 Marni Mann

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License.

Attribution

— You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Noncommercial

— You may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No Derivative Works

— You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Inquiries about additional permissions should be directed to:

[email protected]

Cover Design by Greg Simanson

Edited by Dawn Higham

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, brands, media, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to similarly named places or to persons living or deceased is unintentional.

PRINT ISBN 978-1-935961-90-1

EPUB ISBN 978-1-62015-094-8

For further information regarding permissions, please contact

[email protected]

.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012919590

To Brian, my everything,

my dreams are all possible

because of you.

CONTENTS

MORE GREAT READS FROM BOOKTROPE

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

From the very first word I typed of

Memoirs Aren't Fairytales

to the last sentence of

Scars from a Memoir

, you've never left my side, Mom. You gave me more than just your shoulder, your time, and your advice. You gave me everything I needed. Dad, your smile was my fuel. James Watson, my voice of reasoning, you turned ugly into brilliance, panic into excitement; you supported every step I took. Jody Ruth and Jo Hall, lots of X's for everything you both have done for me. Jesse Freeman, Tracey Hansen, MaryAnn Kempher, Ashley Allen, your words wrap around me and squeeze me like a hug. Katherine Sears, Ken Shear, and Heather Ludviksson, thank you for believing in me. To my team, Adam Bodendieck, Dawn Higham, Greg Simanson, and Steven Luna, you gave this novel everything it needed—a life, a face, a voice, a clear direction—and I couldn't have done this without you. And to my readers, thank you for your kindness and support, and for taking the time to tell me how my novels have affected you. I cherish your words and compliments.

A L

ULLABY

I have scars that chant to me, that scream to me, that burrow into my soul.

Good-bye my past, hello my new life—or so I thought.

Death follows like shadows waiting to dance.

The sun never shines on these parts.

My old scars are tracks stuck on rewind, trying to sing to me.

But my past is louder.

Every day, every night, every breath, my memories call to me.

Come out, come out, come out to play.

Why won't they stop calling?

They haunt me like new shadows, a reminder of heroin.

I was a slip of a girl caught up in fantasies, believing she rode a dragon…

Not knowing she was the meal.

I need my scars to remind me that I still live, that I am still alive, trying to stay alive.

They teach me a lullaby to addiction.

—James Watson

-1-

I HAD BEEN RUNNING TO THE TOILET every few minutes. If I didn't leave the bathroom soon, I'd miss Dr. Cohen calling my name. The ceremony had started twenty minutes ago, and a lump filled my throat. My chest fluttered. Something held me back.

With my hands on each side of the sink, I leaned forward, my nose inches from the mirror. The acne and blemishes had cleared. My tangled mess of hair had been chopped to my chin. Blue eyes stared back with unpinned pupils. Most of the signs were gone.

“Are you ready, Nicole?” Allison asked. The bathroom door was open, and her head poked through.

“I'll be there in a second.”

She smiled. “I'll see you out there.”

For the first time in the eight years I'd lived in Boston, there was a glimpse of the old me. The girl I'd been before getting raped and dropping out of college. I looked…normal. That word was as foreign as “pretty,” but there was some of that, too. The change was more than skin deep, though. Energy pulsed in my veins. My head was clear; my limbs felt attached.

My hand itched, and as I scratched, my eyes followed. In the middle of my palm, I pictured a mound of dope. I wanted to kiss every grain, craving the numbness.

I shook my head, pushing the hunger away.

Looking in the mirror again, I straightened my collar and smoothed the stray hairs that had curled from the humidity. The speech I'd written was in my pocket. I took it out, tucking it under my fingers.

The hallway was empty; the only noises were my clicking heels and my breathing. Allison had told me to breathe in through my

nose and out through my mouth when I was feeling anxious. My gag reflex set in during the exhale. She hadn't told me how to breathe when I was nauseous.

The back door of the rec room was locked, so I went around to the front and through the open doorway. Rows of folding metal chairs ran like bars around the aisle that coursed through the middle. There were a hundred seats, and they were all full.

The counselors sat to the right of the podium, facing the crowd; the other graduates sat to the left—they'd already completed their speeches. Their skin ranged from dark to light, wrinkled to smooth. Like cancer, addiction could affect anyone. I wasn't the oldest at twenty-eight, but I felt ancient.

Dr. Cohen, the head counselor, announced my name and then took a seat next to Allison, who gave me a wink.

To keep my brain busy, I counted each step down the aisle. I didn't look at the people who turned in my direction. I forced my lips to smile and tried to keep my feet steady by focusing on what was in front of me. I knew how an athlete felt when she won a gold medal; tomorrow would be another race.

“Hello,” I said into the microphone. My hands shook as I unfolded the piece of paper. The light blue lines on the page turned to waves; my handwritten words, swirls of black. Everything was spinning. An older man uncrossed his legs, then crossed them again. A woman coughed. In my head, a clock ticked.

I held each side of the podium. “My name is Nicole Brown,” I said. “And today, I'm ninety-three days sober.”

Once everyone stopped clapping, I spoke about moving from Bangor to Boston. How Eric, my best friend, and I had become addicted to coke; weed and alcohol weren't strong enough. Blow led to heroin. The tingles, sparks, and melting were my love, and I'd fallen for the needle, too. I told them how I'd spent the next five years: tricking and stealing for drug money, getting shot in the chest, and having a miscarriage. My arrest had made front-page news, but I told them about it anyway.

Cold, hard truth poured from my mouth. I bared my heart, and that was something I never thought I'd do. The faces in the crowd weren't judging my honesty; they were filled with trust and kindness.

My chest relaxed, and my hands stopped shaking. This was the release I needed. As I glanced around the room at the wives, husbands, parents, grandparents, and friends of the addicted, I crumpled up the piece of paper. They deserved my eye contact and emotion.

I ended my speech with the last night I'd spent on the streets before serving two-and-a-half years in jail. Michael, my brother, had found me on the corner and tried to stop my pimp from beating me. The sound of the gun going off, how I'd held Michael in my arms while his blood pooled over me. And the doctor's final words: “Michael didn't survive.”

Tissues wiped noses, and sniffles echoed. The eyes looking back at me dripped with tears, but the eyes didn't belong to addicts. They belonged to victims. People who watched, helplessly, as those they loved were swallowed by addiction. They knew this story all too well.

Dr. Cohen hugged me and whispered, “I'm so proud of you.” In my hand, he placed a coin with an engraved triangle. On one side of the triangle was

sobriety

, on the other side,

anniversary

, and in the middle,

90

.

The coin felt cool against my sweaty skin, and the color matched the ring I wore on my right hand. It was from Henry, the son of my best friend Claire—he'd given it to me right after Claire died in the hotel fire. He told me to wear the ring when I got sober; I'd put it on just this morning.

After Dr. Cohen thanked all the guests for coming and invited them for lunch, my parents walked over to me. They had visited twice while I was in prison, but I hadn't seen them on the outside since the night Michael was murdered. Their brown hair was heavily mixed with gray. Wrinkles flowed from their forehead to their cheeks, and puffy, dark bags hung under their eyes.

Allison had explained how parents were affected by their children's addiction: sleepless nights, worrying about the health and whereabouts of their child, and constant fear of them dying. My parents were grieving Michael's death, too. It showed.

Mom hugged me first, filling my nose with her vanilla and fabric softener scents; aftershave and mouthwash for Dad. Their smells were the one thing that hadn't changed.

“Are you hungry?” I asked.

They shrugged.

I brought them to the cafeteria; I didn't know what else to do with them. I placed a sandwich and chips on my tray. My parents grabbed fruit cups, and we found seats at the end of a long table.

“We didn't know…” Mom said. Her fruit sat untouched. Dad's too. A quarter of my sandwich was already eaten.

When I'd gotten to Step Nine—make direct amends with the people I'd harmed—I'd sent my parents a letter confessing the things I'd done while on heroin. The only thing I'd left out was my miscarriage.

“I'd already hurt you enough,” I said now. “I didn't know how to tell you this too.”

The way I had killed my baby, a shot of dope too strong for her little body, was as sick as inviting someone to kick me in the stomach. But I was asking them to trust me again. With truth came trust.

Dad covered my hand with his. “If you don't learn how to forgive yourself, you'll never stay sober.”

My parents were seeing a therapist and attending Nar-Anon meetings. Dad's words matched Allison's. But were they going to learn how to forgive me?