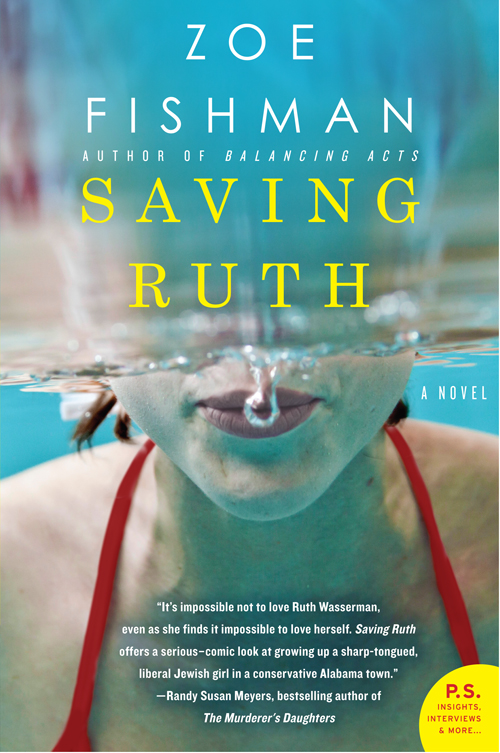

Saving Ruth

Authors: Zoe Fishman

Saving Ruth

Zoe Fishman

We'll talk of sunshine and of song,

And summer days, when we were young;

Sweet childish days, that were as long

As twenty days are now.

â“To a Butterfly” by William Wordsworth (1801)

“P

lease turn your iPod off,” the flight attendant barked as she made a counterclockwise motion with her finger. I nodded in response and pretended to press the Stop button as I inched down in my seat and gazed out the window. Red dirt, pine trees, swimming pools, giant churches, and car dealershipsâall encased in a wall of shimmering heat. Summer in Alabama.

Reflexively, I smoothed my hair. As soon as I stepped off the plane, it would take on a monstrous, frizzy life of its own. And then there was my outfit. If I had deliberately planned to look this way, I could see how my parents might take it as a giant “fuck you.” My ratty, navy blue Michigan sweatshirt hadn't seen the inside of a washing machine in an easy six months. I could smell the pot and cigarettes emanating from its fabric from just sitting on the air-conditioned plane. Once I stepped into the humid heat, the stench was going to envelop me and everyone in my path. Innocent bystanders were going to tumble to the ground, covering their mouths with their hands and gasping for air.

My jeans were just as abusedâthe same jeans that I had begged my mother for right before school had started.

“Mom, everyone has skinny jeans. If I show up for college without at least one pair, I'm doomed, I'm telling you.”

“A social outcast. Ruth, really?”

She fingered the price tag in disgust, but I could tell I almost had her.

“Mommmmmmmm, please? I mean, c'mon, they look good, right? You can tell I lost some weight.”

“Don't tell your father about this,” she whispered, surrendering to me.

I had never owned fancy jeans before, mostly because I'd never really been able to fit into them. I could get them buttoned and zipped, but my flesh would bulge over the waistband like raw dough. Last summer had been the beginning for me. Ten pounds came off before I left for college. My mom told me that I was a

late bloomer

and lit up like a Christmas tree every time I entered the room. I hated that phrase, “late bloomer.” It conjured up Georgia O'Keefe paintings and kumbaya circles. Blooming? Please. I had just laid off the McDonald's.

Looking down at those same jeans now, I cringed. Thirty-five pounds later, the term “skinny jeans” was a joke. They hung on me, with ripped knees and frayed hems that trailed behind me like seaweed. I hadn't showered in days. Well, two days.

I had planned to wake up early that morning, pack the rest of my belongings that hadn't already been shipped home or stored elsewhere, and make myself presentable. Up early and on to the airport. All it took was one phone call, however, and good-bye plan. I had been out all night. What I had envisioned as a civilized taxi ride to the airport (some indie crap on the radio; me looking out the window as we drove through campus, smiling slyly as a rousing pictorial montage of my freshman year flashed through my mind) had turned into my roommate Meg yanking me out of bed and us both running around our dorm room like maniacs, trying to stuff everything into my too-small suitcase. I had made my flight, but just barely.

The plane's wheels hit the runway, and I was officially home for three months. It seemed like an interminable amount of time. What the hell was I going to do? I made a mental list: lifeguard, coach, and not gain weight. Hang out with Jill and M.K. Be nice to my parents. Really. And David, of course. My brother. This year I'd spoken to him less than I had spoken to even my most random acquaintance. You know, the girl that you sat next to in your humanities class but never saw elsewhere on campus? Yeah, that girl and I had a deeper bond than the one that I had with my flesh and blood.

The seat belt light went off, and everyone immediately jumped up as though we were actually going to move in the next ten minutes. In front of me, a family of blond and permed mulletsâmom, dad, and two sonsâstruggled with their suitcases in the overhead bins.

“Dangit, Bobby, I done told you to help me!”

“Mama, can we git corndogs on the way home?”

“Not now, Bobby.”

“Mammmmmmmmmmaaaaa!” The littlest one's mouth was ringed in red. Kool-Aid mouthâa hallmark of the Deep South. I was home.

I filed out of the plane and walked toward baggage claim. The airport was quietâa ghost town almost. Black-and-white photos of football teams and debutantes in frilly cupcake dresses holding parasols lined the walls.

My phone rang.

“Hello?”

“Yeah, Ruth?”

“Yeah?”

“It's David. Can you speed it up? I'm circling the pickup point because they won't let me park.”

I picked up my pace. “They won't let you park? No one is even here. Who are you blocking?”

“I know, I know. So speed it up, okay? I'm getting dizzy.”

“Okay, okay.”

I reached the baggage carousel, and there she wasâmy destroyed suitcase. Misshapen and split, with electrical tape encasing it in its entirety. My mom was going to kill me. I grabbed the handle, which poked out of the silver cocoon apologetically, and rolled/carried it out the door. The air hit me like a bucket of melted peanut butter. In the distance, I could see David's car chugging toward me. He honked a hello, and I waved, feeling strangely shy.

He pulled up beside me and got out.

“Hey hey, stranger,” he said, stopping for a moment to take me in before reaching in for an awkward hug. He looked good, but then, he always did. Brown hair, blue eyes, and lean muscles. Beyond having the same face shapeâsquare, but easily turned round thanks to ample cheeksâwe didn't look anything alike. My girlfriends had always swooned for himâsomething that annoyed the hell out of me when I first realized it but then became amusing as I got older. Watching them strut and giggle in his presence had become a sort of sociological study for me. The line between intriguing coquette and desperate clown was a thin one, and I had seen many girls teeter on its precipice in his presence.

“You look good?”

His appraisal was more of a question than a statement. This happened a lot. People who knew me as my former, larger self were uncomfortable when they saw me now. It was hard to tell whether they were jealous or concerned. Most likely it was a little bit of both. My reaction to their reaction was mixed as wellâwhat I knew was probably a perverse sense of pride along with immediate defensiveness.

“Thanks,” I answered.

“Skinny,” he added.

“You look good too,” I offered.

“Jesus, what the hell happened to your bag?” He took the handle from me, and it rolled on its side like a seventeen-year-old basset hound.

“Long story.”

“Mom's gonna kill you,” he said, surveying the damage. He looked up at me and laughed.

“I know,” I sighed. “Let's go already. This heat is brutal.”

He tossed my bag in the back, and we got in. The interior smelled like Febreeze, French fries, and cigarettes.

“You smoke?” I asked.

“Sometimes.”

“Since when?”

“Since whenever, I guess.”

“But what about soccer?”

“What about it?”

“Your lungs? Athletes don't smoke. It's weird.”

“Okay, then, I'm weird.”

I examined him. This close, he looked tired. Gray circles ringed his eyes, and his fingernails were gnawed to the quick. Strange. Or maybe it had just been a while since I'd sat this close to him.

“Take a picture, it will last longer,” he mumbled. I fiddled with the radio.

“How long have you been home?” I asked.

“Since yesterday. I got in around dinnertime, I guess.”

“How was the drive?”

“Fine. Long. A lot of traffic.”

“How's Mercer?”

“Same.”

I sighed. It was going to be a long summer. We passed a Super Wal-Mart, and I thought of the mulleted plane family. Did Bobby ever get that corndog? And how did Kool-Aid come off human skin? Soap and water seemed impossibly mild. I grimaced, thinking of poor Bobby's teeth.

“You seen Jason yet?” I asked.

“No, not yet. Gonna go down to the pool and meet him later, actually.” Jason was the head lifeguard and pool managerâthe year-round keeper of all things pool-related. You'd get an email from him about Fourth of July relay ideas in February. He lived for summer.

“Cool. And do you know when swim practice starts?”

“We have a kickoff meeting on Fridayâkids and parents. School ends next week, so we'll start right up, I guess.”

I was already tired, thinking of the kids. I was in charge of the six- to ten-year-olds. The first few weeks were always the toughestâgetting them used to me and the routine was hard enough, never mind teaching them to swim the entire length of the pool. Seeing them hold up their ribbons when swim meets were overâtheir excitement oozing out of every tiny, water-pruned poreâalways made it worth it, though.

David was in charge of the older kids, which was its own mess of hormone-fueled distraction. There was nothing like seeing a fifteen-year-old boy in a Speedo to remind you why being a teenager sucked. The combination of skinny limbs, errant pubic hair, and giant Adam's apple was almost blinding in its awkwardness.

He made a left into our neighborhood. There was the Smith house in all of its manicured lawn glory. Felicia Smith and I had played Barbies together as kids. She always wanted Ken and Barbie to go to church. I was more from the Ken and Barbie having lots of sex school, and thus our friendship was pretty much over before it began.

“Do the Smiths still live there?” I asked.

“Naw, they moved out a couple of years ago. I think to Tampa or something?”

“Oh. Who lives there now?”

“Not sure. I think a black family. I saw a kid playing in the yard on my way out to pick you up.”

A few houses down was the Crawford place. Its front yard was carpeted in orange pine straw, and no fewer than five cars were parked on the front lawn at any time. The eyesore drove the whole neighborhood crazy, but the rumor was that the dad was in prison, so they were left alone. I'd never seen anyone go in or out of there. I imagined the inside to be straight out of

Hoarders

. They were probably all buried alive under an avalanche of Jimmy Dean breakfast sandwich boxes and velvet paintings of wildlife.

And suddenly, we were making a right into our driveway. I was home. It looked so much smaller to me now, as if college had turned me into a giant. My dad had mowed the yard for our arrival, and the earthy smell of grass clippings hung in the humid air.

“Here we are,” said David. “Home sweet home.” We looked at each other then, and in everything we did not say passed a history that only the two of us would ever understand. I guess that's what family is. Awkward car rides and stilted conversation aside, you would always have that.