Save the Cat! (16 page)

Authors: Blake Snyder

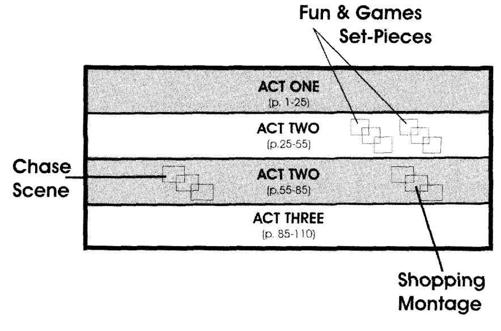

In any storytelling venture, the most burning ideas you have for scenes are what must be laid out first. These are scenes you're sure are going to go into your movie. It's what made you want to write this puppy in the first place. For me, most often, these are funny set pieces, followed by that great scene where we introduce the hero, and maybe the finale. Well, write each idea on a card and stick it up on The Board where you think it goes. It may wind up in another place or may be cut out, but damn it feels good to get those scenes off your chest. Yup. They're up there, all right.

And look at what you have.

What you have is a whole lot of blank space. Gee, aren't you glad you didn't start writing? All those really great ideas that were

b

u

rn

ing

to be written don't feel as big as you thought they were. And the story doesn't seem so likely to write itself once the ideas are written down and put up on The Board. The great way the movie starts or the chase at the middle or the dramatic showdown that felt so full, so easy to execute in your head, isn't all that much stuff when you see it there naked. Up on the board, they're just a small part of the whole. But if you want to see these wonderful scenes come to life — and have a

reason

to live — work must be done. Now the hard part begins.

THE MAJOR TURNS

The next cards you really must nail in there are the hinge points of the story: midpoint, Act Two break, Act One break. Since you have the advantage of the BS2 you know how vital these are. And even though you may come at it a whole other way, I always try to figure out the

major turns

first.

I start with the midpoint. As discussed in the previous chapter, it's an "up" or "down. " Either your hero (or heroes) reach a dizzyingly false victory at page 55 or an equally false and dizzying defeat. In most cases, nailing the midpoint will help guide you — and it is the one decision you must make before you can go on. Most people can nail the break into Act Two. The set-up you've got, and the adventure, or at least the beginning of it, is the movie in your head. But where does it go from there? The midpoint tells you. And that's why figuring it out is so important.

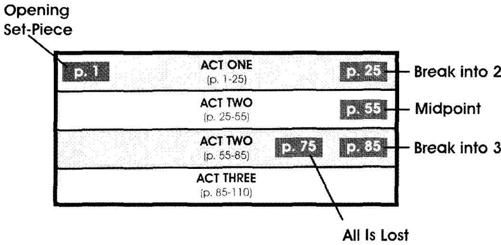

With the midpoint nailed, the All Is Lost is not too hard to figure out. It's the flip of the midpoint. What about the "up" or "down" of the midpoint can be reversed to create its false opposite? And though it may take you some time to adjust both, give it a try. If you nail these two points, the Break into Three is usually cake. Now your board is starting to flesh itself out. It should look more like this:

OVERLOADED ACTS AND BLACK HOLES

For me, my biggest problem is mistaking the cards for something other than beats of the story, something other than actual scenes. This is especially true in the early going as I lay out the set-up and the action of the first act. I give myself three or four cards for the first

IO

pages, that's three or four scenes to get me to the catalyst. But a lot of times what I'll see spread out there are seven or eight cards with things like "the hero is a wrongly accused felon" next to "the hero is a saxophone player." Well, these are not scenes, this is backstory. And these cards will eventually be folded into one card labeled "Meet the Hero" during an actual

sc

en

e in

which he walks into a room and we see him for the first time.

As stated in the previous chapter, a lot of this backstory, these character tics and set-ups need to be... set up. And all your great ideas will go on cards and just pile up here like BMWs on the 405 at rush hour. Never fear, it will all be pared down eventually. Point is to get it all out. This is the time to try anything, think of

everything,

and stick it all up there to see what it looks like.

More confusion comes when scene sequences are laid out up on The Board. Though things like "a chase" involve many scenes and

can range through indoor and outdoor set-ups, it's actually only one beat. So what usually happens is you have five, six, seven cards that are a sequence. Well, these will fold into one eventually but for now will look like this:

One great part about using The Board is the easy way you can identify problem spots. When you have a

black hole

— a place in your script that you can't figure out how to connect one chunk to another — you know it, 'cause it's staring you right in the face. All you have to do is look at The Board and cry. And believe me, those black holes just sit there and taunt you, hour after hour, day after day. "What's wrong, Blake? Can't figure it out? Got a little...

STORY

problem?" But at least you know where it is and what has to be done to fill in the blank spots. You've got nine to

IO

cards per row that you need to fill. And you have to figure it out.

THE ETERNALLY LIGHT ACT THREE

The funny part about laying out these cards is: In the early going, you almost always have a light Act Three.

It's usually two cards. One labeled "the Hero figures out what to do now" and the other labeled "the Showdown."

Ha! Kills me every time I see it.

And you always keep putting off fixing this.

Not

to fear.

Eventually this too will give way. Your mind will flood with ideas and Act Three will begin to fill up. If not, then go back to Act One and look at all your set-ups and the Six Things That Need Fixing. Are these paid off in Act Three?

If not, they should be.

What about your B story? Whether it's the true love story or the thematic center of the movie, this must be paid off, too. In fact, the more you think about tying up all the loose ends, the C, D, and E stories, recurring images, themes, etc., the more you realize all the screenplay bookkeeping that has to be accounted for in Act Three. Where else can it be done? (What? You gonna pass out pamphlets at the movie theater?)

And what about the bad guys? Did you off all the lieutenants on your way to killing the uber-villain? Did all of the hero's detractors get their comeuppance? Has the world been changed by the hero's actions? Soon you will find your Act Three crowded with cards and ideas to fill up the final scenes. Nine or

IO

cards will be required to do this.

Guaranteed.

COLOR-CODING

Now here's a really cool thing. And it wastes a lot of time! But it's also important. How each character's story unfolds and crosses with others needs to be seen to be successfully worked out. This is where your Pentels come in. Color-code each story. See what Meg's story cards look like written in green ink and Tom's story cards are like written in red. And when you put them up on The Board, you can see at a glance how the stories are woven together — or if they need to be re-worked. This is one instance where you will not know how you lived

before

you used The Board. And seeing these beats up there makes you realize what a potential nightmare it would be to try to figure this all out while writing. Screenplays are structure. Precisely made Swiss clocks of emotion. And seeing your different colored stories woven together here makes you realize how vital this planning can be. But color-coding can be used for other things too:

> story points that follow and enhance

theme

and

repeating imagery

can be color-coded.

> minor character arcs

can be traced with your Pentels.

> c, d, and e stories

can get the color-code treatment.

And once you have your multi-colored cards in place, you can step back and see the genius (!) of your design.

All this is intended, of course, to ultimately save you time. What could be worse than being in the middle of actually writing your screenplay and dealing with these placement questions? It's a lot easier to see and move cards around on a board than chunks of your own writage that you've fallen in love with. It's a lot harder to kill your darlings by then. By organizing first, the writing is more enjoyable.

STRIPPING IT DOWN

Forty cards. That's all I'm going to give you for your finished board. That's roughly

IO

cards per row. So if you've got 50 or if you've got

2O,

you've got problems.

Most likely you will have more than you need. And this is where the rubber meets the road, when you must examine each beat and see if the action or intent can't be folded into another scene or eliminated altogether. Like I mentioned previously, I usually have problem areas. Set-up is a biggie for me. I have 20 cards sometimes in the first row. I think there is so much to say, so much I'm not getting across that I overcompensate. But then I look at how these beats can be cut out or folded into others. If I'm honest, if I really admit that I can live without some things, it starts to cut down. I get it down to nine cards.

And that's perfect.

I will also have a lot of sequences. Like chases or action set pieces that stray all over the place. This is easy to fix. Simply write CHASE on this section, no matter how many scenes, and consider it one beat. Usually that's all it is as far as advancing the plot is concerned.

In areas where I'm light, like the problem area of Bad Guys Close In, I usually cut myself some slack. And in some spots, where I know I don't have all the answers, I occasionally even leave it blank and hope for a miracle during the writing process. But in the back of my mind, I know these areas will have to be addressed at some point. Laying it out lets me know where the trouble spots are.

+/- AND ><

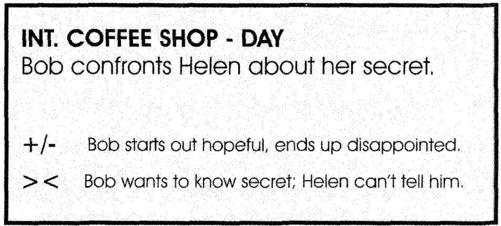

Now that you have your 40 cards up on The Board and you're pretty sure this is how your story goes, you think you're done, but you're not. Here are two really important things you must put on each card and answer to your satisfaction before you can begin writing your screenplay:

One is the symbol +/-. The other is the symbol ><.

These two symbols should be written in a color pen you have not used and put at the bottom of each card like this:

The +/- sign represents the emotional change you must execute in each scene. Think of each scene as a mini-movie. It must have a beginning, middle, and an end. And it must also have something happen that causes the emotional tone to change drastically either from + to — or from — to + just like the opening and final images of a movie. I can't tell you how helpful this is in weeding out weak scenes or nailing down the very real need for something definite to

happen

in each one. Example: At the beginning of a scene your hero is feeling cocky. He's a lawyer and he's just won a big case. Then his wife enters with news. Now that the case is over, she wants a divorce. Clearly what started as a + emotionally for your lawyer hero is now a — emotionally.