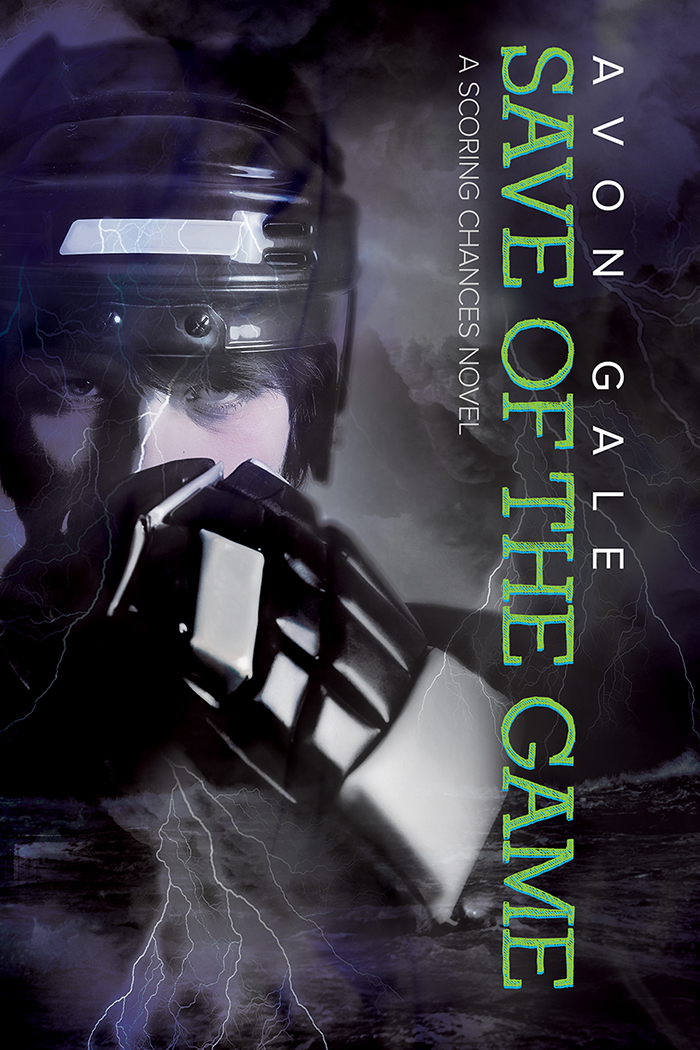

Save of the Game

By Avon Gale

A Scoring Chances Novel

After last season’s heartbreaking loss to his hockey team’s archrival, Jacksonville Sea Storm goalie Riley Hunter is ready to let go of the past and focus on a winning season. His new roommate, Ethan Kennedy, is a loud New Yorker with a passion for social justice that matches his role as the team’s enforcer. The quieter Riley is attracted to Ethan and has no idea what to do about it.

Ethan has no hesitations. As fearless as his position demands, he rushes into things without much thought for the consequences. Though they eventually warm to their passionate new bond, it doesn’t come without complications. For their relationship to work, Ethan will need to learn when to keep the gloves on and let someone help him—and Riley will have to learn it’s okay to let someone past his defenses.

To Morgan, for being a fantastic muse, cheerleader, problem solver and friend. Couldn’t do this writing thing without you, darlin’.

Thank you to everyone at Dreamspinner Press for being so wonderful to work with—especially my editor, Liz Fitzgerald, who deals so patiently with all my questions, comma splices, and autonomous body-part actions.

The structure of minor-league professional hockey in the States is a bit confusing and is constantly changing as teams open, fold, and relocate. I thought it might be a good idea to provide a quick-and-dirty rundown, at least as it pertains to the

Scoring Chances

series and the characters you’ll meet along the way.

The National Hockey League (NHL) has thirty teams, and each team has an affiliate American Hockey League (AHL) team. The primary purpose of the AHL is to serve as a development league for the NHL, allowing promising players and recent acquisitions/draft picks to improve their hockey skills and physical conditioning. Teams can also “call up” players from their AHL affiliate when necessary, to replace injured players or to give valuable playing experience to potential prospects.

Players on the NHL team can also be sent down to the AHL, if it is deemed a good idea for the player’s individual development.

The ECHL, or East Coast Hockey League, which is the league in which the

Scoring Chances

series takes place, is a double-minor league, or the league directly below the AHL. There are currently twenty-eight teams in the ECHL, and most are affiliated with an AHL team—with an eventual goal of adding two more teams so it is even in number with the NHL/AHL. There have been cases when one ECHL team is a shared affiliate between two NHL teams.

Confusing? All you really need to know is that the ECHL is a feeder league for the AHL, which is a feeder league for the NHL. In the

Scoring Chances

series, all the NHL/AHL affiliates are correct as of time of publication, but it should be noted that these can change quite often in between seasons. All ECHL teams, their locations and their affiliates in the

Scoring Chances

series are fictional (with the exception of the Cincinnati Cyclones).

Like the AHL, players can be “called up” and “sent down” as necessary.

It’s important to note two main differences between the ECHL and the other two leagues. The ECHL is not dependent on a draft, so coaches are free to choose their own roster. Anyone can try out for a spot. The other difference is money. And this is a big one—ECHL players generally make about $12,000 per year (plus housing expenses), compared to about $40,000 a year for your average player in the AHL. Of course, the amount is much higher for an NHL player—but not quite, say, the level of your average NFL player.

In the first book in this series,

Breakaway

, Jared refers to the ECHL as

Easy Come, Hard to Leave

, which is a moniker I learned from reading Sean Pronger’s excellent book,

Journeyman: The Many Triumphs (and Even More Defeats) Of A Guy Who’s Seen Just About Everything In the Game of Hockey

. I cannot recommend this book enough, and reading the hilarious and informative anecdotes of Sean Pronger’s career—played primarily in the ECHL—is what made me want to write about minor-league hockey players in the first place. The book also provided a lot of insight and ideas for the character that would become Jared Shore. Like Sean Pronger, Shore is a veteran “journeyman” who’s spent his long career playing for a multitude of teams and wearing a lot of terrible jerseys along the way.

If you’re interested in how minor professional hockey came to be a thing in the southern United States, I also highly recommend

Hockey Night in Dixie: Minor Pro Hockey in the American South

, by Jon C. Stott. This book proved to be an excellent resource and made me appreciate the tenacity of those determined to sell ice hockey to Southerners obsessed with college football (or, in my family’s case, college basketball).

I have tried to keep true to the rules of hockey, both in game play and administrative operations within the ECHL—without being a stickler. Any glaring errors (or convenient road-trip stopovers) I blame on artistic license.

RILEY HUNTER

might not have ended the previous season as a champion, but he was determined the next year was going to be different.

He spent the summer training harder than ever, attending a few camps, and working with a former AHL goalie coach to sharpen his skills in net. If the Sea Storm didn’t win the Kelly Cup, Riley worried he was going to end up traded. And that meant another two seasons—if not more—fighting for the starting spot, just so the scouts would notice him. While goalies matured more slowly—and had longer careers—than guys who played other positions, Riley wasn’t comfortable with complacency. He had a new backup on the team this year, and Riley had to be at the top of his game.

Lane Courtnall, Riley’s friend and former teammate, thought Riley was just being paranoid. Lane was their best player last season, the league’s rookie of the year, and was playing for the Maple Leafs’ AHL team after just one season with the lower-league Sea Storm. Riley was proud of Lane, but he missed him too. Riley had never had a roommate before, and he’d hoped Lane would want to live with him for the season. He was looking forward to having someone else there when he got home after practices and long road trips. But since Lane was in Toronto, Riley was once again living on his own.

As Riley got settled in his new apartment, he wondered for the hundred thousandth time if the apartment was too nice, or if he shouldn’t have gotten himself a new car or the surround-sound system. He spent a lot of time making sure he didn’t look like a rich kid who could buy whatever he wanted, even though he was. And it wasn’t like people didn’t eventually find that out, because there weren’t a lot of hockey players from Wyoming, and a quick Google search provided a lot of links to his family’s spacious ranch at the foot of the Tetons as well as how much they were worth.

Riley knew he was probably being ungrateful, given that he would never have to worry about money. He knew how incredibly rare that was. But he was constantly worried that having so much money kept him from being a better goalie. That it took away some of the hunger that you need to make it in hockey, to climb up until you had a shot at the big leagues. He thought about the stories he heard in the locker room, about guys whose parents drove two hours one way to take their kids to games, through snow or ice and in cars where the heat sometimes didn’t work. How they’d pack a cooler of ham sandwiches, Cokes, and string cheese, and head out before the sun was up, just to make it on time.

And Riley would remember how his driver would take him to practices and games in one of his parents’ luxury cars and wait for him with the heater running the whole time. How he’d wait to leave, sometimes hiding or shivering in the cold after the other kids and their families left, just so no one saw the uniformed man opening the door for him. How he would ride home in the warm, quiet dark of the car, and it didn’t matter if his team won or lost, if Riley had played well or not. It was always the same ride.

His phone beeped, alerting him that he had a new text message. It was from Ethan Kennedy, the defenseman the Storm had acquired before the trade deadline last spring. The rowdy Kennedy, who had a heavy New York accent and was a huge fan of the New York Rangers—a team Riley hated, by virtue of being a New Jersey Devils fan—had bunked with him for a few weeks during the finals. He’d gone back to New York after the Storm lost in the playoffs. Riley hadn’t been sure if he was coming back or not, but the text message indicated he’d just gotten back to town, and would Riley mind picking him up from the airport?

And oh, he got a cheaper rate by flying into Tampa, which was three hours away. Was that a problem? And one last thing. Riley didn’t need a roommate by any chance. Did he?

Riley looked around his apartment, which was nice and clean and quiet. Just like it always was, except for those few weeks last spring when Ethan was there. He was loud and messy and always in Riley’s space, left half-full cans of Pepsi everywhere, drank whiskeys with dubious-sounding names, and smoked like a chimney.

be there in 3 hrs

, Riley texted and grabbed a few boxes of coconut water out of his fridge. The idea of coming home alone after games reminded him of those car rides in Wyoming, and he was getting tired of the silence.

ETHAN KENNEDY

hated flying. He hated it. He might have been the only guy in the ECHL who liked the bus rides.

It wasn’t being in the clouds that bothered him. Not really. It was the part where there was never enough room, ever, in any of the places related to air travel—in the airport parking lot, the shuttle bus, the ticket line, the security line, the seats at the gate, and in the small-ass little planes that now flew everywhere that wasn’t a continent away.

He was in a middle seat, in the last row of the plane, which meant he couldn’t even recline. And there were a thousand old people on this flight—it was going to Tampa, so that figured—who were all coughing or waiting for the bathroom, which was, of course, right behind him.

The woman next to him kept giving him disapproving looks, probably because of his tattoos, which were visible since he was wearing a sleeveless shirt. The man next to him was reading a book called

The Marriage Garden: How to Heal the Flowers of Love

, and it had nothing to do with sex. Ethan knew this because he kept peeking to see if it did. There were no pictures at all, but every now and then the man would sigh and lean back with his eyes closed.

Maybe he wished he’d planted some bulbs in the Slutty Singles Garden instead of the marriage one. If Ethan’s sisters or his cousins ever saw a dude reading a book about the “Flowers of Love,” they’d move their flowers to some other garden so fast there’d be nothing left but empty dirt holes. Or something.

He would have tried to sleep, but he was too keyed up. He was happy to be going back to Jacksonville, even if he didn’t know where he was going to live once he got there. Or, come to think of it, how he was going to get to Jacksonville from Tampa.

He’d figure it out, though. If Ethan Kennedy was good at anything, it was figuring shit out last minute.

It took forever to get off the plane once they landed. Ethan tried not to hit anyone or jostle them, but he really wanted a smoke and some food that wasn’t a package of graham-cracker-cookie things and half a ginger ale. It made him clumsy and short-tempered, and he had to remind himself he couldn’t yell at people who were the same age as someone’s grandma.

When he was finally out of the sardine can that passed for an airplane, he ignored the crowd pressing toward baggage claim and found an empty gate with no flight assigned to it. He sat in a chair and breathed quietly, until the restless anger and the tiredness and the distraction separated enough for him to think clearly through all three. He found his phone and scrolled through the numbers, wondering who the fuck would come get him at this time of night, three hours away, and maybe have an extra room.

Ethan texted Riley Hunter, because he’d stayed with the guy for a few weeks when he first showed up last season, and they’d gotten along fine. Riley was quiet and Ethan wasn’t, and even though he liked the Devils and talked to himself and had 67,000 boxes of disgusting coconut water in the fridge, Riley was a good guy. Hard to get to know, but Ethan hadn’t been there very long.

He’d planned on bunking with Ryan Sloan that year, as it seemed like the perfect solution. He and Ryan got along like gangbusters or whatever that expression was. He’d been in Tampa for fifteen minutes, and he was already sounding like a retiree. Sloany’s roommate from last season was playing up in Toronto. But then Sloany had texted him a few weeks earlier, telling him he was moving into his girlfriend’s place on the beach because, with their combined income, they could afford the mortgage. Ethan was bummed, but he hadn’t been 100 percent sure at the time he was going back to Jacksonville at all.