Salt Creek

Authors: Lucy Treloar

About

Salt Creek

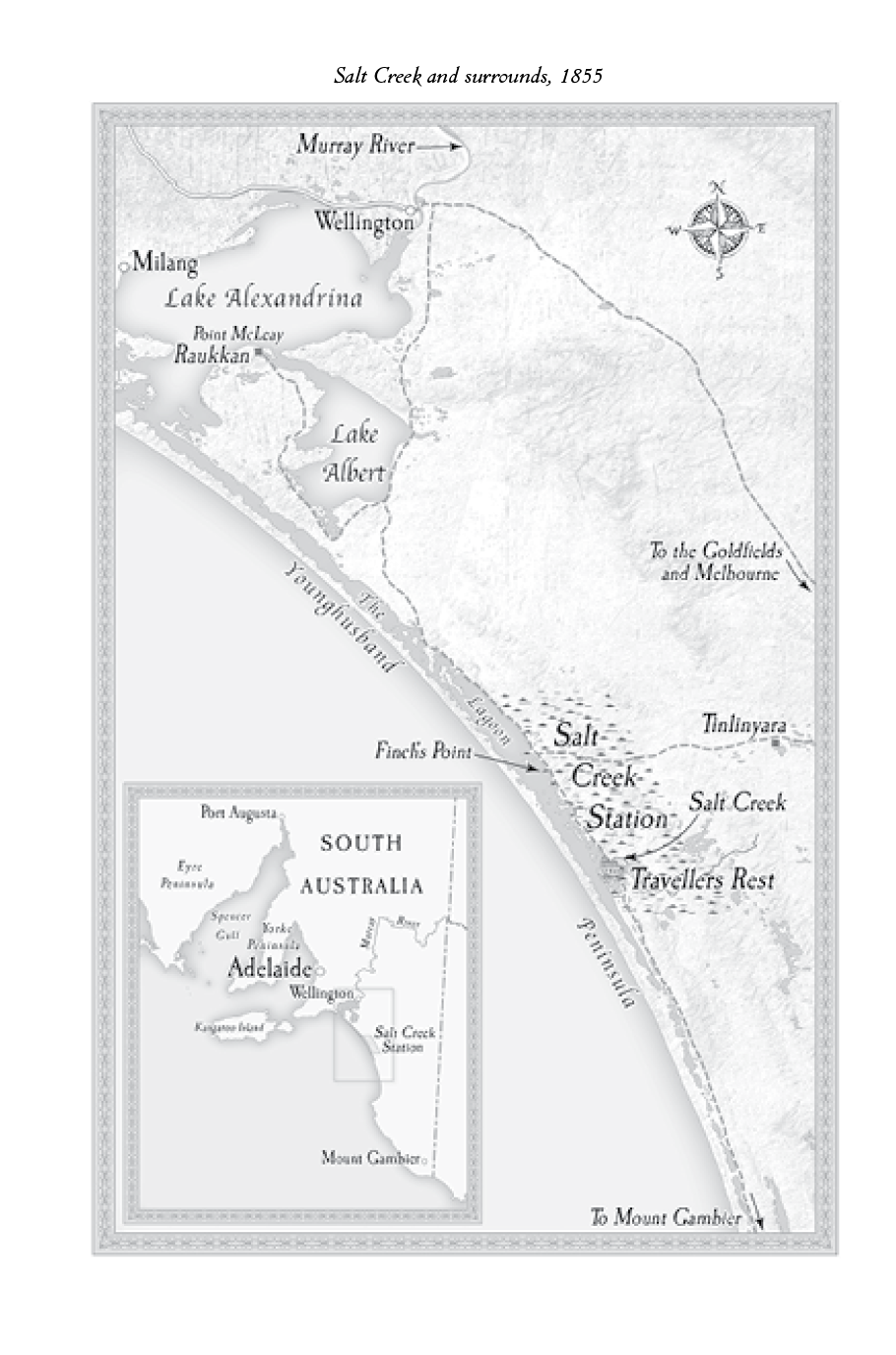

Salt Creek, 1855, lies at the far reaches of the remote, beautiful and inhospitable coastal region, the Coorong, in the new province of South Australia. The area, just opened to graziers willing to chance their luck, becomes home to Stanton Finch and his large family, including fifteen-year-old Hester Finch.

Once wealth political activists, the Finch family has fallen on hard times. Cut adrift from the polite society they were raised to be part of, Hester and her siblings make connections where they can: with the few travellers that pass along the nearby stock route â among them a young artist, Charles â and the Ngarrindjeri people they have dispossessed. Over the years that pass, and Aboriginal boy, Tully, at first a friend, becomes part of the family.

Stanton's attempts to tame the harsh landscape bring ruin to the Ngarrindjeri people's homes and livelihoods, and unleash a chain of events that will tear the family asunder. As Hester witnesses the destruction of the Ngarrindjeri's subtle culture and the ideals that her family once held so close, she begins to wonder what civilization is. Was it for this life and this world that she was educated?

Contents

For David, Jack, Will, Catherine and James, and for Daddy (always missed) and Aileen, with love

South Australia Act 1834

An Act to empower His Majesty to erect South Australia into a British Province or Provinces and to provide for the Colonisation and Government thereof

15th August 1834

Whereas that part of Australia which lies between the meridians of the one hundred and thirty-second and one hundred and forty-first degrees of east longitude and between the southern ocean and twenty-six degrees of south latitude together with the Islands adjacent thereto consists of waste and unoccupied lands which are supposed to be fit for the purposes of colonization And whereas divers of his majesty's subjects possessing amongst them considerable property are desirous ⦠that in the said intended colony an uniform system in the mode of disposing of waste lands should be permanently established Be it therefore enacted by the King's most excellent majesty ⦠and that all and every person who shall at any time hereafter inhabit or reside within his majesty's said province, Or provinces, shall be free and shall not be subject to or bound by any laws orders statutes or constitutions which have been heretofore made ⦠But shall be subject to and bound to obey such laws orders statutes and constitutions as shall from time to time in the manner hereinafter directed be made ordered enacted for the government of his majesty's province, or provinces, of South Australia.

From the Letters Patent under the Great Seal of the United Kingdom erecting and establishing the Province of South Australia and fixing the boundaries thereof

(19 February 1836)

On the North the twenty sixth Degree of South Latitude On the South the Southern OceanâOn the West the one hundred and thirty second Degree of East LongitudeâAnd on the East the one hundred and forty first Degree of East Longitude including therein all and every the Bays and Gulfs thereof together with the Island called Kangaroo Island and all and every the Islands adjacent to the said last mentioned Island or to that part of the main Land of the said Province â¦

Provided Always

that nothing in those our Letters Patent contained shall affect or be construed to affect the rights of any Aboriginal Natives of the said Province to the actual occupation or enjoyment in their own Persons or in the Persons of their Descendants of any Lands therein now actually occupied or enjoyed by such Natives.

CHAPTER 1

Chichester, England, November 1874

MAMA OFTEN TALKED OF THIS HOUSE

when I was a child, and of its squirrels with particular fondness. She mis

sed them as she missed all about her life here. They were fastidious, she said, and always prepared for flight. Their plumy tails jerking, they would hold a nut in their tiny hands, turning it and turning it looking for the weak point, angling their heads and tilting the nuts, their tiny teeth flashing, yet could not always penetrate the shell. I watch one now through my drawing room window as it flickers beneath the oak, stopping to pounce, to sample, to bury, before flaming up the trunk. It is cold now; the breeze blows in and I shut the window. The squirrel glares at me from its branch. It has its habits and instincts that it must follow, as most of us do, I suppose. There was no point in my mother preparing for flight. Her sense of duty and her love were together too great.

I am a lady now and have a fine house and garden and a long walk to the gate. I even have a lake, with bulrushes and ducks and swans.

I saw such birds constantly, many years ago now, on my family's property, which stretched as far as a person could ride across in a day, where birds filled the sky and the lagoon by our house; where the swans were black.

About that time I remember a great deal, some parts more clearly than others. There is a trick of the light here, late in the afternoon, late in summer, at the end of a spell of hot days, when looking from a window upstairs to the lake my mind slips and for a moment I am not here. The grasses are silvered and the waning sun lights them up and the damselflies hover and I expect to see Charles striding up the path with Skipper at his heels, to see a slender raft skimming around a corner, and Addie laughing and Mama for a wonder in good spirits. But it is not so.

It is strange to me that I never felt so alive as then, when we had so little and the possibility of death was our constant companion. Here where I want for nothing it is dull, but I have made my choice and must live with it. I imagine myself sometimes like a thwarted squirrel, holding my life, chewing and nibbling with no way to get inside.

I am respectable now, without taint as Grandmama advised, lest people become curious. What choice do I have? There is my boy to consider and no blemish must attach to his name. I have Grandmama to thank, for sending me here and leaving me this house, for saving me. Why she had always been fond of me, I am not sure; perhaps it was only that she liked my way with horses. And now I am a widow, with wealth enough to indulge my whims. I run a school for the town's orphans and poor. Finally all my learning, like this house, has a purpose. Mama taught me well.

Beecham is grander by far than anything Papa ever dreamed of building on the Coorong or of any that I saw in Adelaide; it is too big for me. Yet I would give it up for a week, a day, an hour in the valley of shells among the sand hills of the peninsula, or for the touch of the first north wind of spring against my face. A part of me will always live at Salt Creek though it is on the far side of the world.

It has been closer to me of late, its outlines growing clear again. Not two weeks ago letters and an old tin trunk crammed with items from the past arrived from South Australia. It was dented, dusty still, and a finger drawn across its skin left a smudge on my fingers. Could it be the grime of the Coorong after such a journey? On a whim I licked it from my fingers â salt â and swallowed to keep it safe. Superstition. I visited Fred in London only last week, and we talked of those years in Salt Creek. Now I can think of little else.

It is a Sunday today, and quiet. I miss the sounds of the young voices. I will ring for tea soon and Ruby will bring it up, then a walk perhaps. Our dear old hound Sal will be slow and Kitty will bound in loops around her. Leaves are falling outside the window. Autumn is here. And there is Joss coming up the drive, hat on and scarf about his neck against the cold. I would know his walk anywhere. Early home from his rambles today. He wishes to become an architect and has many fine ideas; drawing has always been a great love of his. He lifts his head to the windows, searching them, and I see that it is not Joss, but someone taller and older. It is my past come to meet me.

CHAPTER 2

The Coorong, South Australia, March 1855

THE JOURNEY TO THAT PLACE WAS LIKE

moving knowingly, dutifully, towards death. I have seen beasts as resigned. People say it is not so, that they are ignorant to the end, but this is only what people hope. I knew our purpose in travelling there, how Papa had pinned his last tattered dreams to it, which I imagined visible as a flag slipping listless above the dray. Although Mama was as sad as I ever saw her, yet we knew or thought that our all, our very lives and futures, depended on Papa. It was unthinkable not to go with him.

Two days by horse and cart to Wellington, the river crossing, and three more days on a dray had brought us to the edge of our new property â our home, if such it could be called â the bullocks blowing and slobbering at each plodding step. It must be familiar to Papa and Hugh and Stanton. They had hardly finished taking the cows down the stock route to Salt Creek before they had to return to Adelaide to collect us. I did not believe any crop could grow on it or any livestock thrive. Everywhere were rolling grey shrubs and here and there a tree grown slantwise in the wind, I supposed, though it was still enough that day. If the land was an ill-patterned plate, the sky was a vast bowl that curved to meet the ground a very great distance from us in any direction we cared to look. There was no going beyond its rim.

Hugh and Stanton rode ahead and Papa drove the bullocks. The way was so worn down that its edges were a foot up the sides of the dray in places. Sandy soil spilled onto the dry old churnings of hooves and wheels. The route spread wide elsewhere, its centre as uncertain as an inland sea, and Papa had to stand in his seat to see where we should go: empty now. Prospectors and the gold escort had come this way once, but the inland track had stopped that, Papa said. A person might think, to hear him, that such scarcity of life was a virtue.

I was in the dray with Addie and Mama and Albert and Fred and the new babe, Mary, who was fretting. Her white fists waved about and battered at Mama's breast. Hungry again. Mama unbuttoned herself and obliged. I looked away, not that there was very much to see about us, but it was preferable to Mama's sad face. Grandmama and Grandpapa and dear friends left behind for Papa's newest venture.

When news came that the ship carrying the fine fat sheep that Papa had purchased had gone down off the coast of Van Diemen's Land, Papa had paced the drawing room, backwards and forwards across the window, tall and straight as he moved from shadow into light and back again.

Mama, hovering in the middle of the rug, said, âYou will come about. You will. You have us safe.'

Papa looked at her. His deep set eyes were rather empty. âYes,' he said absently, when she approached him, and patted her arm.

âIt might be a blessing. Who would oversee the flock? Everyone has left for the goldfields.

You

could not do more.'

It was true. For the last several years Papa had often been away at the dairy farm in Willunga, taking Hugh and Stanton with him. The house was quiet in their absence, which we did not like, though Mama said it had been worse in the whaling station days when a month or more would pass before he could come back to us from Encounter Bay. Of course, we had two maids then, and a cook, so it would not have been very hard on Mama despite there being four of us already and her soon to have Addie. He had made a loss on the whaling station, whales not being as plentiful as they had been, which was a bitter pill. He had been obliged to sell most of his subdivisions in Adelaide to cover costs. At least the dairy had prospered. As Grandmama said one day: âIf only he had been content with that.' He borrowed against it to buy sheep, and then it seemed that everything began to go wrong, and this time there was nothing to fall back on. The bank foreclosed on the farm and finally the house in Adelaide must be sold. At least Papa had kept the stock, and before collecting us from Adelaide had driven them through the hills and down the stock route to Salt Creek.

Now, Addie hung over the back of the wagon, holding a stick against the dust to make a trail. It was not safe and a girl of eleven was too old for such childish games, but if Mama did not bestir herself to say something, I saw no reason why I should. Albert and Fred began to squabble over a grasshopper that had jumped into the dray. Albert wished to tie thread about one of its legs and keep it as a pet and train it to do I know not what, while Fred wished to examine it.

âGive it back, Al. It set on me,' Fred said, and after a jostling wrested it back and held it in his cupped hands. A grasshopper claw protruded between his fingers, pushing at the air. It would be warm and sweaty in there, with a strong odour of boy, and not very comfortable.

âHester,' Mama said to me wearily. Once she would have put the creature into a jar that we might observe it, the spring in its muscular legs, the joints, its bulging eyes. It would have been an opportunity for learning. âSee, it has its bones on the outside, while we have our bones on the inside,' I imagined her saying, and since she didn't, I did. Fred and Albert glanced from me to Mama, who remained silent. I wished Mama would take herself in hand. They were growing disobedient. Fred wouldn't be a boy for much longer; he was growing fast. It made poor Albert appear even younger. Fred was beginning to draw away from him in his interests. It took the quickness of a grasshopper to bring them together again.

I would have given anything to ride ahead with the boys. Stanton was only a little older than me, and Hugh was a clumsy rider. He had laughed and teased at his first sight of me on the bullock dray. âLook at Miss Hester in her fine carriage.'

His self-satisfaction made me boil up inside. I sat straight, and held my hands in my lap and looked down my nose at him. âWhere you should be, Hugh. Away from those reins. Look at poor Birdie. You'll ruin her mouth.'

He jabbed the reins, sending Birdie shuffling and dancing. His moods travelled down the leather and he did not know the way of stopping it. He was missing an audience for his opinions and his amusements afresh, I daresay, having spent part of winter and most of spring on the Coorong with Papa and Stanton building the house, and was no happier than I at the turn our lives had taken.

âIt will be five years and more before you go back to town, if it's as soon as that,' he said. âWhat use will your fine gloves be until then?'

âI will, I tell you. I'll be back before you,' I said, though I knew it was not true, for how could I, a girl, hope to escape? I felt very wretched when people talked like that, but it wouldn't be my fault if I were not in town before then; I had made up my mind to that before we left.

Now I looked down at Fred, so like Addie, with his dark hair and pale skin. âShow me,' I said.

He opened a well into his hands between thumb and forefinger. I looked, but it was so bright outside his hand, where we were, that I could not see in. At a lurch into a pothole we threw out our hands to brace â Fred too â and the grasshopper, a brown flecked bullet, made good its escape over the side. âOh,' we all said, for a moment united in loss. Any amusement, even one as slight as this, had been welcome.

Hearing the commotion, Addie pulled her stick in and scrambled down the dray, her knees and boots tangling in her petticoats. âWhat? What is it?' in her little hoarse voice. She was our English rose, so Papa said. Grandmama said different. She said Addie was the apple of Papa's eye. I supposed that if she were an apple or a rose I was a bramble. It was ridiculous how fast I grew; on that there was general agreement. My dresses were always too short. The boys would tease, and nothing that Mama and Papa said stopped them.

In Adelaide Mama had tugged at my skirts as if she could make the fabric stretch. I was forever having fittings until the money ran short. After that Mama would look at me, her eyes fixing on the expanding gap between hem and floor. âIt will have to do until you are finished growing.'

âOr the sheep stop drowning,' Stanton said, sitting on the edge of the kitchen table, his hands in his pockets, and swinging his legs.

Mama frowned. âStanton, I believe you are needed elsewhere.'

He lifted his brow, smoothly jumped from the table and sauntered out, his hands still in his pockets, as if it were his own choice rather than Mama's request that had made him leave. The girls went wild for Stanton, with his ruddy curls and hazel eyes and dandified clothes â flowered waistcoats and the like. He was like a hot cat blinking in the sun. They would all like to pet him.

Mama returned her gaze to the problem at hand, which was me. âIf you bend a little it will not appear so bad.' Since I must also stand straight it was quite confusing. Once I heard her say to Papa, âShe's fifteen. Where will it end? Surely soon, else no one will want her.'

Strange to say, I would prefer it if she were saying such things again, though I did not like it then. Since the little ones died she has cared for nothing. First Louisa, not one year old, after Papa had lanced her gums to ease her teething. Then dear Georgie. The flux and a hot spell had been enough to take him away. He was the dearest little fellow.

We had all been sad since, and Addie fearful that she might fall ill again. For a few days it had seemed we might lose her too. She put her hand to her forehead often. âFeel me, Hester,' she said. âAm I hot?' I could not reassure her, only distract. In quiet moments when I found a place to be alone I sometimes touched my own forehead and cheeks and pressed against them a handkerchief sprinkled with a little of Mama's rose water to cool myself, and wondered. I did not wish to die.

Now, Addie shook my shoulder. âHester, tell me.'

âJust a grasshopper, Addie. Gone now.'

âOh.' Her mouth was round with disappointment. She scraped her hair from her face.

âWhere's your ribbon?' I asked.

She looked about at the parcels and trunks. Her eyes lifted to the broken way behind us. She shrugged.

âNever mind,' I said. âThere will be something in Mama's workbasket that will make you nice again.' Really she was old enough to manage on her own, but we had fallen into the way of babying her while she was ill.

She scrambled over our possessions to retrieve the basket and returned. I found a piece of cherry thread and combed my fingers through her hair and made a plait, binding its end with the red thread. Addie tried to pull it around so she could see it, but her hair had been cut short when she had the fever and had not grown again.

The dray continued its abominable lurching. We were on our run, but it made no difference to anything. We were here, not home. The journey was not flight; it was scarcely movement. I conceived of travel as sleek as water, not this dull connection with the ground and the wheels with a seeming will to plough deeper into it. I wanted to go and go and never stay still and have no one tell me what to do now or tomorrow or ever.

Midday. The sky was high and hard, and my face scorched by wind and sun despite my bonnet. A patch of skin showed between the end of my sleeve and the top of my glove. I tugged the glove up and eased the sleeve down. Now I could blush to think of the care I took of that inch strip of white skin, as if my future rested on it. We were filthy, Papa and the big boys worst of all, the sweat and grime making muddy rivers down their faces. The dust that dragged in the air about us was a cocoon we could not escape.

I rested my chin on my hands and my elbows upon my knees and Mama said not a thing. The track flattened into a river of sandy soil bordered by scrub and grass trees and lifted towards a rise. And then Skipper, our dear greyhound, lifted her head and gave a warning bark and I did see something â two women standing a way off above the rutted track. They carried baskets on their backs and wore a sort of grassy fringe at their waists. There was a boy with them of about Fred's age, I would say. He appeared so at ease, as if he'd merely paused at his front gate and looked over it to take in the passing traffic. Strange to think this desolation must be as familiar to him as town was to me. How fortunate we were to have clothes. Perhaps they would become civilized under our influence, as Papa hoped.

The face of one of the women was pockmarked. She stared at us, which I did not think polite, and looked fierce and haughty and wary together, and I remembered the stories about the wreck of

The Maria

somewhere along this coast and how its passengers were murdered, including nice Mr and Mrs Denham and all their children who used to live nearby in Adelaide. (I did not remember them, of course, because I was a baby when those shocking events occurred, but Mama spoke kindly of them.) Papa said there was no reason to be fearful now, that the blacks understood justice, and I tried to remember that.

Addie got to her feet and called out, âHello, hello.'

âAdelaide!' Mama said. âSit down.'

But Addie waved again, and I had just enough time to see the younger of the native women break out a grin â her teeth so white, like the whites of her eyes, that they startled me â before Mama reached across, squeezing Mary who set up a cry, and gave Addie a hearty slap. âSit down at once!'