Sally Heming (57 page)

Authors: Barbara Chase-Riboud

I didn't need anything anymore. I didn't need Martha.

Martha needed me to free, but I didn't need Martha to free me.

I, like my mother and her mother before her, had survived

love.

CHAPTER 43

NOVEMBER 1826

Notice from Richmond

Enquirer,

7

Nov.

1826

executor's

sale

On the fifteenth of January, at Monticello, in the county

of Albemarle, the whole of the residue of the personal property of Thomas

Jefferson, dec, consisting of valuable negroes, stock, crops, etc., household

and kitchen furniture. The attention of the public is earnestly invited to this

property. The negroes are believed to be the most valuable for their number

ever offered in the state of Virginia. The household furniture, many valuable

historical and portrait paintings, busts of marble and plaster of distinguished

individuals, one of marble of Thomas Jefferson Ceracci with the pedestal and

truncated column on which it stands, a polygraph or copying instrument used by

Thomas Jefferson for the last twenty-five years, with various other articles

useful to men of business and private faculties. The terms of the sale will be

accommodating and made known previous to the day. The sale will be continued

from day to day until completed. The sale being inevitable is a sufficient

guarantee to the public that they will take place at the times and places

appointed.

[signed]

thomas

jefferson

R

andolph

Executor of Th. Jefferson dec'd.

It has long been known that the best blood of Virginia may

now be found in the slave markets....

frederick douglass,

1850

Thomas Jefferson Randolph

, better known as Jeff, sat in his grandfather's study, his long legs

stretched out under the old man's writing table. He was the image of Thomas

Jefferson.

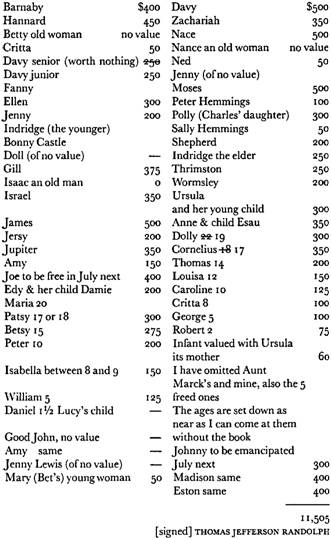

He stared at the laboriously written inventory. It was

pitiful, he thought. Not more than five years ago, these people would have

brought four or five or even ten times these amounts. Of course, the most

valuable slaves were not at Monticello, but at Poplar Forest, where they were

about seventy odd who would bring in money as prime laborers. The Monticellian

slaves were all more or less fancies, highyellow or white slaves, highly

trained, but they were too old. He had never known Monticello without them.

He had lined them all up on the west lawn, practically in

front of the window he was now gazing out of, and had gone around from one to

the other making the inventory with Mr. Matter, the auctioneer. His nurses, his

playmates were all there. He had taken out his own slaves— Indridge, Bonny

Castle, and Maria—and those of Aunt Marck's, which were the most valuable,

except for Davey Bowles. Damn! Davey Bowles should have been able to bring at

least two thousand.... He had passed each familiar face, some so dear to him,

that tears had welled in his eyes. When he had stood before Fanny, he had

wanted to throw himself in her arms bawling.

Mr. Matter had kept apologizing for the low estimates,

explaining that the bottom had fallen out of the market in the past year and

that prices had plummeted almost eighty percent! At least they would keep the

house with one miserable acre. That was all.

His eyes roved to the miniature staircase at the foot of

his grandfather's bed. The passageway

Would

be sealed at the request of his mother. Only the tiny staircase would

remain. No one had taken the trouble to explain the relationship between the

Hemingses and the Randolphs, but children had a way of finding out what they

wanted to know, thought Jeff. Like the day of the inventory when he had looked

into the eyes of Sally Hemings. He had heard Mr. Matter's automatic whisper:

"Age?"

"I reckon between fifty and sixty," he had

answered. "Fifty dollars," Mr. Matter had said.

And Sally Hemings had said, "Oh my husband,"

looking straight at him.

She had said it, damn it. Clear as a bell. Only once, but

he had heard it. When he had told his mother of it, she had shrugged and said

that Sally's mind was probably wandering with the shock of the sale. She had

never had a husband. Then his mother had announced that she was freeing Sally

Hemings because his grandfather wanted it that way. It meant they would have to

petition the Virginia legislature for her to remain in the state—dangerous.

Of course, Sally Hemings hadn't said those words to him,

for her eyes had been fixed on the Blue Ridge Mountains, and they had had the

most unearthly yellow glow. God damn!...

1

8

12

monticello

CHAPTER 44

JANUARY

1827

The dismantling

of Monticello by

the slave auction of

1827,

the abomination of the sale of my kin, the ticketing and labeling and pricing

of every stick of furniture, every sheet, every curtain, every dish, every

book, painting, sculpture, each clock, vase, bed, table, horse, mule, hog, and

slave that had been Thomas Jefferson's; that had been he, himself; all his

parts and pieces, his choices, his favorites, his ears, his hands, his eyes,

was the sorrow and pity of my life. His life had been parceled and lotted and

priced by the auctioneers who thronged through the house. His life's bits and

pieces probed and handled, weighed, inspected, and priced. Everything, animal

and human, including my own flesh.

I despised the steaming crowd that had gathered round the

west portico of Monticello that January day, come to bid like vultures on the

carcass that had been a man and his house. If only he had not loved everything

so much! If everything had not been love and memory as well as collection!

People arrived by the wagonloads. A county-fair atmosphere

reigned as the prospective buyers strolled in and out of the barns that held

the slaves, and the house that held the objects, their flyers in hand,

inspecting: objects tenderly accumulated in Paris; a house of brick and wood

assembled by my kin; the brilliant English gardens, now brown and colorless;

and the orchards, now leafless and barren; and beyond, the rolling fertile

fields, woods, cascades, and rivers. Already the deep black lands of Pantops

and Tuffton, Lego, Poplar Forest, Bear Creek, Tomahawk, and Shadwell were gone,

now the humans attached to them were going. One thousand four hundred and fifty

lots had been auctioned off that day, forty-two hogs, fifty sheep, seventy

cattle, fifteen horses, eight mules, and fifty-five humans from Monticello—more

than half of the slaves were my sisters, brothers, cousins, nieces, nephews.

And one hundred and twenty from Bedford.

The crowds had begun to assemble early that day. They had

come from as far away as Kentucky for a chance to buy prime black flesh,

livestock, or an object that had been, as I had been, a possession of Thomas

Jefferson. There had been that same lewdness in the air, that same miasma of

death and contempt and titillation that always accompanies the trial, judgment,

and condemnation of a man's life. Around me festered the curiosity about the

great, the aura that sets some men above others and brings out that predatory

hatred of the common for the extraordinary.

My master had left debts of one hundred and seven thousand

dollars. Martha and Jeff had struggled valiantly to save Monticello, selling

off all the other lands and plantations; the lots in Richmond and

Charlottesville, everything. But everything had not been enough. The gods had

demanded and got all but the mansion of Monticello.

Strangers had roamed his precious gardens, treaded his

polished floors, inspected his linen, looked into his barns and the mouths of

his slaves, pinched velvet and flesh, sniffed tobacco and the smell of human

sweat, hefted samples of cotton and the private parts of male field hands,

rubbed their hands over the woolly rumps of Marina sheep and the heads of

pickaninnies, discussed the qualities of Monticello blooded bays and Monticello

pure-bred bodies.

Hatted and veiled, my identity hidden behind my color and

the name of "Frances Wright" of Tennessee, I had roamed the crowds

that day as a freedwoman, despite the danger, willing myself to engrave every

moment in my memory, hoping to save one or two of the children, and vowing

never to forget the sale of Thomas Jefferson.

"If you don't be good, I'll tell Master, and he'll

sell you to Georgia, he'll sell you so fast..."

How often had those words struck terror in a slave child's

heart? How long, how much longer, would they continue to? He had been good, but

he would be sold anyway.

"What do I have, whatdo I have, whatdoihave for this

lot number thirty-four, three prime male field hands, twenty-six to

twenty-nine, broken here at Monticello, in perfect health, no scars, bruises,

defects

of any kind;

never been

whipped, docile, strong, perfect for breeding. What am I bid, whatamibid, three

hundred, four, four fifty. Do I hear five? Five, five twenty-five, six, six,

six. Do I hear seven? Yes seven, seven twenty-five, seven fifty; only seven

fifty for this prime lot, three ... ladies and gentlemen, three prime

Monticello slaves, three for the price of one. Ladies and gentlemen, I ask you,

is this the best you can do? Eight, eight fifty. Do I hear nine? Nine, do I

hear nine, nine, nine, nine—going once, nine going twice, nine going three

times—sold, sold to the lady for nine hundred dollars. Prime, male house slave,

thirty-two years old, Israel, father of seven in the next lot, locksmith and

metalworker. Prime, housebroken pickaninnies, a lot of seven. Just a few years

and they'll be prime field hands or house servants, healthy stock, no

blemishes, light-skinned. Do I hear five hundred? Five hundred once, five

hundred twice, five hundred three times. Sold! Sold! Sold! A female,

twenty-nine years old, breeder, light-skinned, seamstress and cook, perfect for

a housekeeper for a young gentleman; may I start at four hundred? Four hundred

fifty? Elizabeth, Israel's wife. Do I hear four? Four, four fifty, five ...

female slave, fifteen, guaranteed virgin, healthy, bright, best stock of

Monticello, trained as a house servant. Priscilla, Israel's daughter.

"Do I hear three hundred? Three hundred. The best

stock at Monticello. Docile, perfect for a lady's maid. Only five hundred

dollars. Ladies and gentlemen, Christmas was a week ago! I cannot let this

prime female go for less than three fifty. Do I hear three fifty? Yes, three seventy-five.

Do I hear four? Four. Four. Do I hear four? Sold to the gentleman for four

seventy-five. Dolly.

"Prime first-class female. Cook. Thirty-six years old;

served at the President's House in Washington City. Pastry and all-around cook.

Do I hear one hundred dollars? Two? Do I hear three? Three for this treasure

trained in French

cuisine.

Of impeccable stock, guaranteed fertile, mother of three. Three fifty,

do I hear four? Four fifty, do I hear five? Five fifty once, five fifty twice,

five fifty three times. Sold to the lady for five hundred and fifty dollars.

Fanny. One big black healthy mammy trained as washerwoman, midwife, and pastry

cook. Weighs in at two fifty [laughter]. House servant for twenty years.

Sixty-two years old, ladies and gentlemen, I won't lie to you, but she still

has some good years in her. Loves children, mother of eight herself. All them

children in lot fifty-six hers! Loyal, honest, clean house mammy. Do I hear

thirty dollars? Thirty-five, do I hear forty? Fifty? Do I hear... fifty it is.

Going, going gone. Sold. Sold. Doll.