Running on Empty (28 page)

Authors: Marshall Ulrich

In the Poconos, I slowed to a walk as a reporter interviewed me for his local paper. His questions struck me as shallow and irrelevant (“What kind of shoes are you wearing?”), and I was in a bit of a moodâimpatient to be on the road, run on to New York, and get this whole damn thing done with. Not that I was impolite. I answered his questions reasonably well, I hope. Then he asked me something worthwhile.

“What's the first thing you want to do when you finish this run?”

If he expected me to say something refined, like how I wanted to pop the cork on a bottle of Dom Perignon, I'm afraid I disappointed him.

“Three things: I'd like to sit in a chair, take the time to have a meaningful conversation with someoneâand I'd like to stop having to crap in cornfields.”

Funny, he didn't really have any more questions for me after that.

Â

On day fifty-one, I woke up in tears again. What sent me over the edge this morning was having spent the night in bed feeling Heather's warm, soft skin against mine. The prospect of getting up, leaving her, and going out for another day onto the cold, unforgiving highway left me sobbing. Once again, she pulled me close and soothed me, telling me everything would be all right.

God, when would this be over? We had, perhaps, only three more days to go, but nothing was a given. Anything could happen, even in these final miles. If we'd learned nothing else, the road had taught us that lesson quite thoroughly. I was losing faith. Would that be the thing that would keep me from the finish?

No, it wouldn't. My connection with Heather would hold me up. When it felt as if I had nothing leftâno will to continue, no strength to take another step, no air to breatheâher touch and her words would motivate me to keep going. Years before, she had rescued me when I was drowning in my loneliness and taught me how to love again. And now, one more time, she would help me out of my despair so that I could recognize how much I had to be grateful for. The crew, the sponsors, my friends who had come when we called, bringing fresh smiles, clothes, and hot food. My family, including my children, who'd suffered years of having a father who was gone much of the time racing around the world, lost on some level, his heart and soul having taken a blow when Jean died.

Now it was time, finally, to let go of Jean. Years ago, I'd held on to her body just after her death, cradling her in my arms and crying out her name, alone in that bedroom at her parents' house. It had been quite a while, I don't know how long, before I'd released her, willed myself up off the bed, wiped my tears, and gone to tell the family that Jean was gone.

Yes, it was time to let go. Completely, now. Time to rise. Time to go on, finish the race, and then stop running.

How could I not realize that the people who surrounded me today were reason enough to go on? How could I not embrace who and what I had become? How could I not finish? Life was unbelievably simple, and the beauty of it lay in every individual footstep, taken one at a time, over and over again.

Â

When we got started for the day, we headed up Nescopeck Mountain and the hilly terrain. As expected, it was cold and, from all appearances, would stay that way. But now I didn't care much about the weather, as I was moving well and at a fairly good pace. Off in the distance, two huge cooling towers, probably from a power plant, lit up the dark with their pinpoints of light. Winding up and over a two-mile road on a hill, I'd loop around those towers. This epitomized the runâslow and sureâand it also reminded me of approaching the summits on Kilimanjaro, Aconcagua, or Everest. There, you coil around these gigantic mountains, just as I circled the towers here. It put me back in mind, again, of how great this nation is, and the immensity of change we've experienced, from buckboards and buggies to towers and skyscrapers.

Now I was yearning to see those skyscrapers, imagining that I'd catch a glimpse of New York City every time we crested a hill. Perhaps tonight? Surely the glow of the city would reach me . . .

In the afternoon, just after my marathon nap, the entire production crew gathered at the RV. Kevin Kerwin, Kate's husband and the documentary's director, interviewed me, which I can say I handled with more grace than when I'd talked with the reporter. It's to Kevin's credit, though, as his questions were better, and he gave me the opportunity to talk about how important Heather was to my ability to finish this run, about how I wasn't just some empty shell of a man moving down the road, but that I needed nurturing that could come only from her.

This was, I thought, the last I'd see of the documentary crew, as time had run outâtheir contracts had all expired, unfortunately. Kevin, Rick, and Kate would be there to get footage if I made it to the finish, but everyone else would go home. Dr. Paul, too, would be leaving the next day because he had professional obligations.

So I said good-bye to the production crew. Good-bye to Paul. Good-bye to my pride, while we were at it, as I was having trouble even walking because of back pain. I just kept telling myself,

Only a little farther.

At the end of the night, I was fairly chanting,

Not much longer, not much longer. Just one more mile.

Only a little farther.

At the end of the night, I was fairly chanting,

Not much longer, not much longer. Just one more mile.

How often had I said that on this road? How many times had I pushed myself to go one more day, travel one more mile, take one more step? But isn't that the way of any endeavor, of any trial, of any life? Instead of wearing me out, those words propelled me forward.

Besides, the countdown was on. No longer did I feel as if I was on a treadmill, running with no end in sight, emptied of reason and purpose and passion. Now I knewâI could

feel it

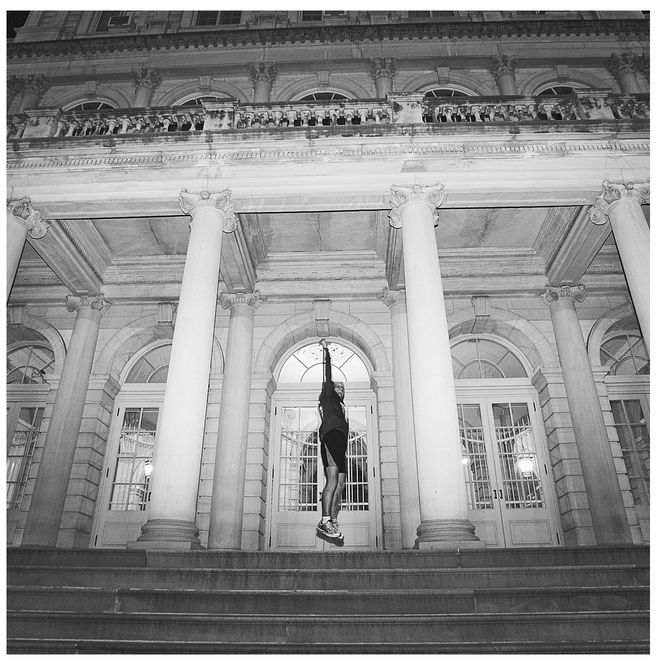

âthat every stride took me that much closer to the doors of New York City Hall, the end of the road.

feel it

âthat every stride took me that much closer to the doors of New York City Hall, the end of the road.

When we ran through the town of Jim Thorpe, named after one of my childhood heroes, it felt as if everything was coming to a fitting close for me. My father had admired Jim's achievements, too, remarked about what a phenomenal and versatile athlete he was, to have played football, baseball, and basketball professionally and to have won Olympic gold in the 1912 pentathlon and decathlon. The champion's humble beginnings and his love and mastery of multiple sports impressed me as a kid, and I felt a certain kinship with him as an adult. I liked that he hadn't limited himself, or thought of himself as achieving success in only one sport. Like Jim, my dad had been an incredibly versatile man, constantly willing to try new things. He'd been a doughnut maker, a butcher, a store owner, a dairy farmer, a pet food manufacturer, and later the president of the National Farmers Organization. He wasn't afraid to do anything, and was good at everything he did. No doubt he liked the challenge of jumping into a new profession every ten years or so, just to make life interesting. I wished Elmer could have been there to go through Jim Thorpe with me, and in a way he was. I no longer felt so alone. It was as if every person who had contributed to who I am accompanied me, anyone who had ever encouraged or challenged me, all those who had loved me, the children who'd followed our progress from their classrooms, the men and women who'd climbed with me, run with me, paddled with me, walked with me in any wayâthey had come with me. All of them were a part of me, and I was a part of them.

Â

The crew was filling out again. Mace had come back, as had Elaine and Taylor, and my friend Tom had joined us. When Mace and I crossed over the Delaware River on day fifty-two, Taylor and Elaine met us at the end of the bridge. We were in New Jersey now! The second-to-last state, and the skinniest of them all. With a little over eighty miles to go, we were knocking down the miles.

My God, this might, just might, happen. We're going to run out of land soon.

My God, this might, just might, happen. We're going to run out of land soon.

Not without one last wrinkle, of course. My back was in knots, and I was moving at a snail's pace. With Paul gone, we did our best to get over it: Tom stretched me, Robert used an electro-stimulation gizmo, and Heather brought me Chinese food. Bless them all! My back was recalcitrant, though. It had had enough these past two months, and it was ready for me to quit. But we kept going, moving slow as molasses.

Welcome to New Jersey!

“The Garden State”

Â

Arrival date: 11/3/08 (Day 52)

Arrival time: 1:30 p.m.

Miles covered: 2,983.0

Miles to go: 80.2

Arrival time: 1:30 p.m.

Miles covered: 2,983.0

Miles to go: 80.2

That night, our last of this long effort, we stayed at the Triumph house. (Seriously, that's Tom's last name, and we stayed at his family's place in Mountain Lakes, New Jersey.) It was the first time we'd been in someone's home since leaving our own nearly two months ago, and Heather said it was comforting to her, to be out of the RV and the hotels, as a guest in a place where people led normal lives.

Tom ran me a hot bath and then helped me into it, holding my arm and steadying me as I sank into the water, my back throbbing. As I slumped into the tub, I wondered if I'd have to crawl into New York City. I knew one thing, the grand masters record was mineâI had smashed the old time, and I could take up to twenty-eight hours to get to the finish, if I had to, to break the masters record, too.

Less than fifty miles to go.

For now, I felt like the luckiest person in the world. My dream was within reach. This would end tomorrow, I was sure. And tonight, as on so many nights before, there was an angel in my bed.

Less than fifty miles to go.

For now, I felt like the luckiest person in the world. My dream was within reach. This would end tomorrow, I was sure. And tonight, as on so many nights before, there was an angel in my bed.

12.

Running Out

Final Day

Â

Â

Â

For more than two decades, I'd been running. Sometimes I'd run away from things; sometimes I'd run toward them. This day, what drew me forward was the promise of reaching New York, our last leg on this long, long road.

If nothing too extraordinary occurred, I'd own this son of a bitch.

Â

“This is going to be ugly, pathetic! I'm going to have to walk all the way to New Yorkâthis is not how I imagined it at all.”

At 5:30 a.m. on what was supposed to be our final day, my back was killing me, and I was in pieces. Yet again, Heather soothed me.

Tom had gotten up before us, and he came upstairs to let us know that he'd already arranged for me to go to a chiropractor friend's house for an adjustment. Grateful, I followed Tom to his SUV. We slowly hoisted my body into the passenger seat, and I winced as he helped me sit down, my leg and back muscles in spasm, tensing and protesting. Like I said:

pathetic

.

pathetic

.

On the way, I was thinking about what wonderful friends we have in Tom and his wife, Therese. Who finds a chiropractor to treat you in her home at six o'clock in the morning? Tom, that's who, because he has exceptional friends of his own. When we arrived, she immediately went to work, positioning me on her table and using a strange instrument, something with a small plunger that tapped my misaligned vertebrae back into place. Would this really work? I was accustomed to chiropractors bending me like a pretzel and then, without warning, snapping my back or twisting my head. This was a lot less jarring, and I wasn't sure I could even be contorted into the right position for a snap or a twist, but it seemed a rather gentle approach for such an intense problem. She was calm and confident, working her way along my spine with that little clicking device, and after about ten minutes, she had me turn over onto my back, measured my legs, and proclaimed that she was done.

That's it? That's going to get me to New York?

Rolling onto my side, I slowly slid my legs off the table and dangled my feet toward the floor. So far, so good. Carefully, I scooted off the table and put my feet down.

Ouch

. My feet hurt.

But wait a minute. If I'm noticing my feet instead of my back, that's an improvement.

This morning, I hadn't even thought about my feet until then. Now, moving across the room, I felt very little back pain. Walking down the stairs and out the front door: even less pain. We thanked the chiropractor and said good-bye, Tom helped me into his car, and we drove to his house. I helped myself out of it when we arrived.

Ouch

. My feet hurt.

But wait a minute. If I'm noticing my feet instead of my back, that's an improvement.

This morning, I hadn't even thought about my feet until then. Now, moving across the room, I felt very little back pain. Walking down the stairs and out the front door: even less pain. We thanked the chiropractor and said good-bye, Tom helped me into his car, and we drove to his house. I helped myself out of it when we arrived.

“Holy shit, I think she cured me,” I said under my breath. Then louder, with emphasis: “No kidding! I think she

cured

me.”

cured

me.”

I grinned at Mace, who was waiting anxiously to see how I was and to head out on the road with me.

“I don't want to jinx anything, but I'm telling you I think she cured me.”

We grabbed our gear from Tom's house and headed back to the stakeout point. I'd put on my long-sleeved Capilene shirt, one of my two favorites, which I'd been wearing every day since Dave Thorpe had bought them for me back in Indiana, and which had been laundered for the first time the night before. (Thank you, Therese!) Those shirts and the matching long underwear had been indispensable the last six hundred miles, as they were the only ones that really worked in the rain and cold, so I'd refused to go without them long enough for them to be cleaned. In fact, like that seemingly eccentric bunioneer all those years ago, I'd worn just my long johns through most of Pennsylvania. To the brand's credit, they hadn't gotten too terribly offensiveâthe fibers stayed relatively odorfree, as Heather had hung them up to air out every nightâbut I appreciated what Therese had done. As everyone knows by now, I love clean laundry.

Other books

The Bucket List to Mend a Broken Heart by Anna Bell

Perfect Victim by Carla Norton, Christine McGuire

September Wind by Janz-Anderson, Kathleen

Forever You by Sandi Lynn

Fighting to Survive (Guarded Hearts Book 3) by Noelle, Alexis

Out of My Mind by Andy Rooney

Just William's New Year's Day by Richmal Crompton

The Good Suicides by Antonio Hill

The Bronze Eagle by Baroness Emmuska Orczy

The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses Over the Hills by Bukowski, Charles