Rose in Darkness (13 page)

Authors: Christianna Brand

‘Free as air. Of course there’s this absolutely monster child complete with monster Nanny and I fear that nothing will induce him, not even me, to pack them off to Mummy where they long to be; but I’ll tell you one thing, darling, not one week will I spend at Hilltop or whatever, with wild originality, it calls itself.’ She embarked upon a lively description of Phin’s house. ‘Even a bar in the corner of the drawing-room, decorated with ever such amusing figures of drunks; and someone, who could only be departed Ena, has painted on them little black Mandarin moustaches and large straw hats, so whimsical! can you imagine?—presumably to fit in with the Chinese decor or Persian or whatever it is—’

‘Persians don’t have Mandarin moustaches?’

‘Well, but there are camels and the Chinese don’t have camels; or do they?’ She broke off suddenly: ‘Sofy—quick, over there, turn in at that pub!’

A small pub-cum-restaurant, done up very chichi, with an outside sign,

THE HEAVENLY ANGEL.

And standing outside The Heavenly Angel—a shining black Cadmus 3000—a Halcyon.

Sofy wrenched the Ferrari across the road, to the momentary discomfiture of Ginger and Bill, a mite too close behind. ‘Go by the side door, Sofy, there’s parking there too and we can creep in that way.’ Sergeant Ellis, reconnoitring for a not too obvious concealment, saw that they stationed themselves round a corner from the bar. He despatched the constable to telephone to Charlesworth for advice, ordered a pint of bitter and settled down to keep watch, from his nook.

The place included a restaurant for lunches and dinners—(‘Tomato soup and scampi for the yobbos, Sofy, and madly enterprising pates for the discerning, what’ll you bet?’)—and the bar, with a woman serving before the gantry and a young assistant. Otherwise it was empty but for a blonde perched curvaceously up on a stool, with the carefully careless tendrils of hair known in the tonsorial profession as turds, and a pretty little face lit by a sort of not un-engaging childish silliness. A miniature poodle sat solemnly on the stool beside her, its fur brushed into clouds of silky white. ‘A Pimm’s for me,’ she said to the barmaid (‘My dear—how predictable can one get?’) ‘—and his usual, please.’

‘His usual?’ said the girl, bemused.

‘Oh, I’m sorry—you’re new here. A little drop of sweet Martini for Monsieur Pow, poured out into—’ the older woman, accustomed, passed over a shallow ashtray. ‘Pow, short for Powder-Puff,’ she confided as though keeping it out of the dog’s hearing. ‘Well, he does look like one, doesn’t he? Or Pouf as the boyfriend wittily calls him and one must admit that he does seem just a tiny bit That Way. Monsieur Pouf—trés gai!’

‘A French poodle, you see,’ said the older woman, evidently familiar with this gambit, helping out her young assistant.

‘Yes, he is and too utterly Left Bank, he doesn’t believe in anything, do you, darling?’

In the L of the room, Sari and Sofy made sicking-up motions into their hands. ‘My dear, one word more of all this tweetiness and I shall go ap-solutely beresk!’

‘Well, fancy!’ the barmaid was saying, rather wretchedly.

‘But talented! Sing your song, darling, till your Uncle gets back from the ‘phone. Sing for the lady!’ She sat the tiny creature into a begging position and began to croon, solemnly conducting him with a newspaper rolled into a baton. The poodle lifted up its damp black nose and soulful almond eyes and now and again emitted a low moan. ‘So come on, now—our song!’—and she sang in a high, fluting voice, rather sweet on the ear—

‘Cerulium was beautiful, Cerulium was fair,

She lived with her grandmuzzer in Gooseberry Square,

She was my ducky-doodleums but now, alas she

Plays kissy-kissy wiz an officer in the ar-till-er-ee!’—and fell into a tinkle of laughter. ‘Oh, darling, beautiful! Only—your accent, we simply must practise and practise...’ A clock chimed the half hour. She glanced up at it. ‘He’s a long time. Who can he be ringing up? One of his damn women, I suppose.’ She unrolled the newspaper and began plucking off little pieces from the corners. ‘He loves me, he loves me not, he loves me, he loves me not—’ But a man appeared from around a corner and she jumped down from her stool and flung her arms about his neck. ‘He loves me!’

Sari’s true love. Phineas Devigne.

Sari said very quietly: ‘Oh, Sofy! In his buttonhole—that’s the same red rose.’

Ginger made a mad dash for the police car. The Halcyon was turning out of the drive, on to the road. ‘Get after him! But don’t let him suspect.’ The girl with the poodle emerged, looking shaken, climbed into a smart little sports car and drove off in the same direction. Bill said, accelerating, ‘It’s the man we saw yesterday, Sarge. At the pub, The Fox - after that fuss about the car keys being stolen. Never seemed to have seen her before, Morne, I mean—but took her in charge and went off with her. That’s the same man. Only he was driving a Rover, then.’

‘Well I’m damned!’ said Ginger.

‘Comes rushing out, gets into this Halcyon and drives off. White to the gills, he was; carrying a newspaper flapping open...’

‘The girl had the paper. He took one look at the headlines—went, like you say, white as a ghost, said some word to her and bolted out. I think she thought he’d done his nut.’

‘I’d rung Mr Charlesworth like you said. He said to stick with the car—if it seemed at all promising, stick with the car and play it by ear, he leaves it all entirely up to you.’ Bill, eyes on the road, jerked his head back towards the place they had just left. ‘What about them two? Miss Morne?’

‘I think she was absolutely thunderstruck, seeing him there. And yet she seemed to be there—well, spying; and now if you say that she knew him... It’s all a bit complicated,’ confessed Ginger, rolling in his seat a bit—the Halcyon was making very good time along the narrow road; his mind registered that the man drove as though he were well familiar with its twists and turns. A couple of miles on, he said: ‘Here’s where the tree fell, Bill.’

‘Yeah, well we saw it yesterday, me and George, following them down to The Fox. Rummy business that!’

It was all a rummy business—so rum as to almost blot out its own ghastly centre—that pitiful Thing, crammed down behind the driving seat of a shining new Halcyon car with, as it now seemed, lying on the dead body, a dying dark red rose...

And now—a gentleman with a Halcyon car, who wore in his buttonhole a dark red rose.

Nanny met Phin in the hall and stared up, leerily, into the haggard white face. ‘My goodness—you look gashly! Had a shock, have you?’

‘What?’ he said, his hand clawed across his forehead. ‘A shock? Yes—yes, a bit of a shock.’

‘Heard the news at last, then? That Miss Sari Morne of yours... Time you come in last night,’ said Nanny, ‘or call it this morning—and rushing off out again, first thing, well, you wasn’t esackly at leisure to settle down to a read of the papers?’

He only half heard her; said dully, ‘Yes, I got an early ‘phone call, I had to go out.’

‘Ringing up all night, they were. And what could I say—you wasn’t back yet.’ She looked him over again, vaguely puzzled. ‘It seems really to have shook you up. She never told you—?’

‘No, I...’ But the front door had remained open and two men now appeared there. ‘Who the devil are you?’

‘Sorry to disturb you, sir. Police, sir. Sergeant Ellis,’ said Ginger, sufficiently recovered to be settling into one of his roles, whipping out the credentials, tucking the badge away again, the quiet, confident young officer, pouring oil with one hand, busily stirring up trouble with the other—‘and this is Constable—’

‘What on earth are you doing here?’

‘It’ll be about the murder,’ said Nanny, eagerly. ‘You knowing Sari Morne and all.’

He made no protestation or denial; simply said in that dull way, ‘You’d better come in then,’ and led the way through to the sitting-room. Sergeant Ellis perched his round behind on the edge of a chair, gazing around with simple admiration upon the Bad Habitat. Phin pulled himself together. ‘Nanny, ring the hospital and say I’ll be held up—’

‘Tell the Register to get on with it?’ prompted Nanny, bossily familiar.

‘The Registrar,’ he corrected automatically. He went over to a small bar tucked away in a corner, decorated rather amusingly, to Ginger’s mind, with little moustachio’d figures in appropriate stages of drunkenness. ‘I’m sorry, but I must get myself a drink.’ He lifted a bottle with an interrogatory glance; Ginger, palm forward, held up a disclaiming paw, observing, while the victim went about his business with a trembling clink of glass against glass, that he had a fine garden here, sir, hadn’t he?

Phin turned away from the bar. ‘Yes, well you haven’t postponed a radical hysterectomy for a nice horticultural chat?’

Ginger would have liked nothing better: deep, velvety crimson—fragrant—vigorous growth—tendency to mildew... ‘It’s your Josephine Bruce, sir. Lovely dark colour, haven’t they? Always wear one in your buttonhole, do you, sir?’

‘Buttonhole? What the hell are you talking about?’

‘Well, you’ve evidently heard about this murder? And, on the woman’s body—’ He broke off. ‘You won’t mind if my chap here takes a few notes, sir?’

‘Notes? What about? What’s all this got to do with me?’

‘You do own a Cadmus 3000, sir, a Halcyon?’

His face grew very cold. But he came straight to the point: ‘You’re not suggesting that I was the man who changed cars with—Miss Morne—at this fallen tree?’

‘

If

anyone changed cars with her. The body was found in her own car.’

‘God knows, I don’t mean to suggest—’

‘Miss Morne knew the woman. She speaks to her at the cinema, gives her a lift home, on the way they quarrel; Miss Morne gets her hands on the woman’s throat—and she’s dead.’

He swung away, so that the liquid in his hand spun in the glass and slopped over the edge. ‘That’s—obscene.’

Ginger sat forward in his chair, bottom out-thrust, fingertips together, looking up at him, eager, inquisitive, a chipmunk. ‘What would

you

say happened?’

‘I don’t know, I’ve hardly skimmed through the thing. But—she’s a highly-strung creature, the mind can play funny tricks. The tree fell—and I believe a tree did fall the night before last—but just after she’d passed. Severe shock. Then later, immediately, any time—even before the tree fell—she came upon the woman by the roadside, dead or dying—might even have been killed by the fall of the tree.’

‘Strangled by one of its branches?’

‘Strangled? Oh God! Well—killed then, and left by the wayside and Sari—Miss Morne—found her there, got her into the car and—either then or when she got home, realised she was dead...’

‘And went off to bed and never mentioned it to anyone. She’s had time since’, suggested Ginger looking down at his own peaked church door of fingers, ‘to have mentioned it to

you

?’

‘Well, I’m telling you—three shocks in a row, she simply fled from the whole situation, let her mind close over it; like scar tissue closing over a festering wound. It happens, you know.’

‘Meanwhile making up this rather clever story about the fallen tree?’

‘Not impossible at all; and by now she quite believes it really happened.’

‘Only why?—if she didn’t kill the woman?’

‘The mind is very strange; it does play these tricks.’

‘Well, no doubt, sir...’ But the chipmunk attitude was wearing on the neck. Ginger rose and went to a tall window, looking over the small orchard where even yet a few apples still hung, golden, among the turning leaves. ‘So you’re saying she never met anyone at the tree.’

‘I’m saying it’s possible. If she did, well, there are other Cadmus cars about; it wasn’t me.’

‘You weren’t out at all, that night?’

‘Yes, I was. I went to the cinema, I can prove that, I spoke to the woman at the ticket box, she can tell you—’

‘No, she can’t,’ said Ginger, reasonably. ‘She’s dead.’

‘Oh, dear God—! Well... Miss Morne herself could tell you,—she ran into me there; though I didn’t know then that it was her.’

And it was true that Sari had said that she’d run into a man in the cinema; (meeting him later, however, had not troubled to add that this proved by coincidence to have been Mr Phineas Devigne whom she had later met again at the pub called The Fox.)

‘What time would you leave the cinema then?’

‘I don’t know. About ten. Whenever it closed. I had to see a patient—a difficult pregnancy; then I came home.’

‘Arriving—?’

‘What

is

this? A cross-examination?’

‘No, no, sir,’ said Ginger, all innocence. He explained: ‘Miss Morne claims to have met a man answering to your description. I’m not even asking you officially. If you object to replying—’

‘Of course not,’ said Phin. ‘Why should I object?’

‘Well, that’s what I thought, sir. But thank you

very

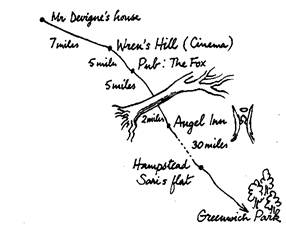

much,’ said Ginger, tamping down any sign of smugness at having succeeded in this neat little ploy, ‘for telling me so. So you won’t mind just playing it, sir, that you did change with the young lady at the tree?’ He stifled repudiation by producing his own notebook and a Biro pen, and proceeding with an outline sketch: a long, squiggly worm of road running upwards intercepted by stabbing, blobs of ink.

Ginger’s map