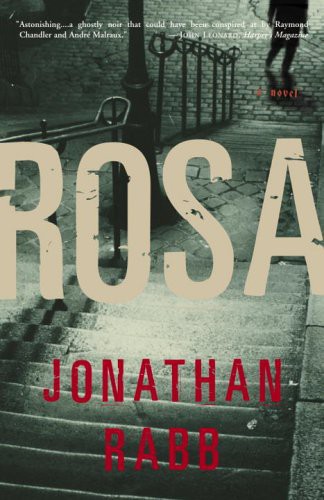

Rosa

Jonathan Rabb

Rosa

A NOVEL

Crown Publishers

Contents

FOR ANDRA

Acknowledgments

I

am indebted to Professors David Clay Large and Peter Fritzsche for their help in bringing to life the Berlin of 1919. I also thank Peter Speigler and Sean Greenwood for their wise advice and encouragement on the earliest drafts of the book—more so for their friendship—and Professor Abraham Ascher for his expertise on the German Revolution and its aftermath. For her wonderful renderings of the lace patterns, I am also grateful to Anne Auberjonois. And to Byron Hollinshead and Rob Cowley, who once again went beyond the call in championing this manuscript, I am indeed lucky to call them friends.

As always, Matt Bialer and Kristin Kiser kept me on the right course with good humor, insight, and enthusiasm. All writers should have such agents and editors.

And finally I would like to thank my family, and especially my wife, Andra, who possess an unending supply of support.

In the last days of the First World War, socialist revolution swept across Germany, sending Kaiser Wilhelm into exile, and transforming Berlin into a battleground. Order returned only when the two leaders of the movement—Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg—were hunted down and assassinated on the fifteenth of January, 1919. Liebknecht’s body was discovered the next morning; Luxemburg’s body, however, remained missing until the end of May

Speculation about Rosa’s fate during those months continues to this day.

This is one possibility.

PART ONE

PART ONE

ONE

1919

1919

B

erlin in December, to those who know her, is like no other place. The first snows take on a permanence, and the wide avenues from Charlottenburg to the Rondell breathe with a crispness of Prussian winter. It is a time when little boys drag their mothers away from the well-dressed windows at KaDeWe or Wertheim’s or the elegant teas at the Hotel Adlon and out to the Tiergarten and the wondrous row of marble emperors along the Siegesallee. Just as dusk settles, as the last flurries of the day swirl through the leafless trees, you can steal a glimpse of any number of little eyes peering up, hoping, just this once, to catch a stony wink from an Albrecht the Bear, or a Friedrich of Nuremberg with his large ears and dour expression. Just a wink through the snow to tell him that Christmas will be kind to him this year. “There, Mama, did you see! Do you see how he winked at me!” And the pride that next morning, bundled up beyond measure, racing out from his fine house on Belziger or Wartburg Strasse to tell his friends of his triumph. “Yes, me, too! Me, too!” Berlin in December.

This, however, was January, when the snow had turned to endless drizzle, so raw that it seemed to penetrate even the heaviest of layers. And whatever civility they might still be clinging to elsewhere, here on the east side of town, all the way up to the flophouses in Prenzlauer Berg, people had little time or patience for such gestures. Christmas had brought nothing, except perhaps the truth about how the war had been lost long before the summer, how the generals had been flimflamming them all the way up to the November capitulation. Oh, and of course, the revolution. Christmas had brought that, a thoroughly German revolution, with documents in triplicate, cries from the balconies, demonstrations and parades, tea still at four o’clock, dinner at seven, and perhaps a little dancing afterward up at the White Mouse or Maxim’s. Shots had been fired, naturally, a few hundred were dead, but the socialists—not the real socialists, mind you—were straightening everything up.

Still, it was the weather that had most people on edge. The rain just wasn’t giving in, and it was why Nikolai Hoffner, rather than waiting out on the tundral expanse of the Rosenthaler Platz, had snuck off to Rcker’s bar for something warm to drink. Years of experience had told him that nothing of any significance was going to happen today: later on, he would come to regret that arrogance. So, with a knowing smile, he had left the ever-eager Hans Fichte up on the square; at the first sign of trouble, Fichte knew where to find him.

Hoffner sat with a brandy (“I’d walk a mile for Mampe’s brandy, it makes you feel so hale and dandy!”), the early edition of the

BZ am Mittag

in front of him. He had not sat like this in weeks, a quiet read to clear the mind. And not because of the nonsense that had been going on out at the stables, or up at the Reichstag: all the pretty uniformed men had managed to disrupt traffic too many times, now, to recount. No, Hoffner had been up to his ears in real violence, genuine terror, hardly the kind plotted in Red pamphlets or designed in back rooms by overfed burghers calling themselves socialists. They played at revolution; he knew another kind. But for today—orders from on high—he was told to leave that alone and join the rest of his breed in the streets to make sure “nothing untoward” would come to pass.

Hoffner finished off the last of his drink and nodded to the barman to bring him another. As he was one of only three people in the place—a man at a corner table, his head tilted back against the wall, his mouth gaped open in sleep; a woman with a beer and bread, her business at one of the nearby hotels temporarily interrupted—the service was unusually prompt. The barman approached with the bottle.

“This, I’m sad to say, will have to be the last.”

Hoffner looked up from his paper. “I’m sad to hear.” He had a steady, reassuring voice.

“It’s this damned rationing,” said the man. “This and another bottle’s all I’ve got for the day. My apologies.”

Hoffner half smiled. “What do you care if the money’s coming from me or from someone else?”

“Simple economics,

mein Herr.

No brandy, fewer people in here to buy my sausages before they rot.” The man opened the bottle. “It’s called the distribution of capital, or something like that. You understand.”

Hoffner’s smile grew. “Completely.”

“And”—the man nodded as he poured—“the money’s not coming from you. It never does. So why don’t you be nice to me today and let someone else pay for the brandy?”

Hoffner reached into his coat pocket and produced a ten-pfennig coin. He placed it on the table.

The man smiled again as he shook his head. “No, no. I like that you don’t pay. You like that you don’t pay. We may be governed by socialists now, but it’s better that you hold on to your money.”

The man popped the cork back into the bottle and headed for the bar. “Time to wake up, Herr Professor

Doktor,

” he said as he moved past the man in the corner. The man at once opened his eyes, looked around in a daze, and then, in one fluid movement, pawed out his beard, picked up his umbrella, and stood. Upright, he seemed far more impressive, though from the look of his clothes, one had to wonder how much sleep he had gotten in the last few days. He peered over at Hoffner. “Is it safe out there,

mein Herr

?”

Hoffner continued to read his paper. “Safe as can be, Herr Professor

Doktor.

”

“Excellent.” The man turned to the barman. “My thanks, Herr

Ober.

” And, placing his hat on his head, he started for the door, stopping momentarily to bow to the lady. “Madame.” He then glanced quickly through the windows, and was gone.

Hoffner scanned through several stories, all of which were doing their best to assuage a devoted readership. The Reds were dead: good old Liebknecht had gotten his in the park, little Rosa in the clutches of a murderous mob, though her body was still missing; Chancellor Ebert could be trusted with the government; business was on the rise, so forth and so on. And yet, even within the lines meant to pacify, the

BZ

had that remarkable capacity to stir up a kind of subdued panic:

Reichs Chancellor Ebert, with the full cooperation of a diligent military, has declared the streets once again safe for the men and women of Berlin. Hurrah! With the National Assembly election only days away, we must thank this provisional government for the speed with which it has put down the Bolshevik-inspired insurgency, and hope that it is equally tireless in its efforts to hunt down the deluded lone sharpshooters who still infest our city. Those living in the area between Linienstrasse and the Hackescher-Markt are advised to remain indoors for the next twenty-four hours.

The woman at the table laughed lazily to herself. Still pretty at twenty-two, twenty-three, she jawed through her bread. She was wearing the unspoken uniform of those girls who sell roses and matches at the restaurants along Friedrichstrasse—the silk-thin dress, ruffles along the low collar and cuffs, the dark cloche hat with its front trim tucked up, just so—except hers was well past its prime, the sure indication that she, too, had progressed. All pretense long gone, she spoke her mind. “It’s so easy to spot one of you,” she said, not looking up. “Long brown coat, brown shoes, brown hat, brown, brown, brown.”

Hoffner flipped to the next page. “One might say the same of you, Frulein.”

She bit into a wedge of bread. “But you won’t. As a gentleman.”

“No, of course not. As a gentleman.”

The woman started to laugh again as she picked at the remaining slab of bread, her fingers like little bird beaks pecking at the crust. “Another glass of brandy for my friend, Herr

Ober,

” she said, her eyes fixed on the bread. “We must make sure to keep our men of the Kripo warm and happy. Who will protect us from the Russian hordes?” Another laugh.

Hoffner folded his paper and placed it on the table. “Alas, Frulein, but the Russians are out of the

Kriminalpolizei

’s jurisdiction. We deal only with the Berlin hordes.”

The man at the bar smiled quietly and retrieved the bottle, but Hoffner shook his head and pushed back his chair, a bit farther than he had anticipated needing. His wife was pleased that he was having no trouble keeping the weight on, a testament to her culinary skills amid all the shortages. Not that he was fat, but Hoffner had a certain image of himself that he was, as yet, unwilling to part with: good height, deep eyes, dark hair (he had gotten the latter two from his Russian mother, likewise the first name), reasonably fit, and with a thin scar just beneath the chin, a worthy reminder of championship days as a

Gymnasium

fencer. At forty-five, however, several centimeters had vanished to the slight roll in his shoulders; the depth of his eyes had relocated south to a pair of ever-widening bags; and while the hair was still full, dark most certainly would have been a stretch. As to the rest, more like distant friends than close companions.

“Thank you, Frulein,” said Hoffner. “But I’m guessing you’ve got better things to do with your hard-earned money.”

The front door opened and a pocket of chilled air quickly made the rounds. There, slick from the rain and out of breath, stood Hans Fichte, his eyes on Hoffner.

“Shut that door,” barked the barman as he placed the bottle back on its shelf.

Fichte did as he was told, and moved quickly to Hoffner’s table. “You’re needed back in the square, Herr

Kriminal-Kommissar.

It’s—” He glanced around, then leaned farther in over the table. “It’s important we get back.” Fichte spoke as if he actually thought someone other than Hoffner might have any interest in what he was saying.

Fichte was a large man, over two meters tall, and with wide, thick shoulders. A strip of flaxen hair, matted in sweat and rain, held to the top of his brow, and his usually gray/white cheeks were blistered in odd blotches of red. A single drop—let it be perspiration—clung to the tip of his nose, which was too long for his narrow face, and which always gave him a look of mild disdain. At twenty-three, Fichte still had a boyish smoothness to his complexion, though the ordeal of the last six weeks was beginning to dig out some distinguishing lines: hardly what one would call character, but it was something.

The fact that Fichte had reached twenty-three—uncrippled and completely unconnected with any of the convalescence asylums that had recently surfaced throughout the city and the Reich—made him something of an anomaly. Fichte had been fit enough to serve his Kaiser in 1914, or at least up through the second week of September 1914, when, in a moment of profound stupidity, he had volunteered during a drill to demonstrate how to use one of the early gas masks, those chemically treated masks that required wetting with a special activating agent immediately prior to use. Hans had not known about the need for the wetting. The gas had come on, he had inhaled, and from that moment on, he had ceased to be fit enough to serve his Kaiser.

Damaged lungs, however, were just fine for the

Schutzmannschaft

(municipal beat cops), and after three years of stellar duty, Fichte had applied and won transfer to the Kripo. He had been presented to Hoffner two and half months ago as his

Kriminal-Assistent

(detective in training), a replacement for a partner of twelve years who had volunteered and then gone missing in 1915. Victor Knig had come as close to a friend as Hoffner had permitted, and his death had taken some time to get over. With the choices on the home front greatly diminished, the

Kriminaldirektor

(KD) had been kind enough to let Hoffner work alone for the better part of four years. Hans Fichte was now the price for that kindness.

“So important,” Hoffner said as he got to his feet, “that you’ve decided to leave the square yourself?” He was waiting for a response. “In the future, Hans, find a boy—there’s always one roaming about—and send him to get me. Yes?”

Fichte thought for a moment, a mental note etched across his face. When it was properly filed, he nodded, and then headed for the door.