Rome: An Empire's Story (9 page)

Rome’s comparative advantage over its rivals must have been institutional. No other explanation is really plausible. Geopolitics may have played a part, but Rome’s location was not so good, nor so unique. The economic resources of Rome’s immediate hinterland were not that impressive, especially when compared to those of Etruria or Campania. Romans enjoyed no technological edge over their opponents, not even in the field of warfare. The best that may be said is that at some period Roman citizen armies had become more experienced than those of some of their opponents. Nor is it really plausible to argue that Romans were more militaristic than their opponents. The celebrations of warriors in funerary art throughout central Italy, as well as those treaties, make it clear that it was not at all unusual for societies to be warlike. Short wars between neighbouring peoples were in fact probably more or less the norm, a competition for booty, prisoners, and prestige. It may be that many of the early wars remembered in Roman tradition consisted of raids and counter-raids of this kind.

16

The difference came when Romans began to impose on their defeated opponents permanent obligations. During the fourth century it seems Romans began to institutionalize their position as pre-eminent city of Latium to create a federation of states with Rome at its heart. The innermost circle comprised the Latins, citizens of those communities with whom Romans enjoyed certain reciprocal rights, such as intermarriage and trade. Beyond them were other allies, the

socii

. Rome’s allies were communities, not individuals, and to begin with most were bound to Rome by permanent and unequal treaties. Imposing a treaty of this kind almost always followed military victory. Greek cities concluded wars with treaties and then reverted to splendid autonomy. Rome had, it was said, agreed to several limited-term truces with Veii, and its treaties with Carthage imply equality between the parties. But the treaties that created allies were signs of permanent subordination. Allied states retained a separate citizenship and a notional internal autonomy—not that Romans did not intervene when they wished—but they had to supply troops when Rome demanded and they had very limited independence when it came to relations with other states. By the early second century

BC

, Romans regarded these lesser allies as subject to other kinds of authority too. One of the earliest

surviving decrees of the Senate is a bronze tablet recording restrictions issued in 186

BC

on the worship of the god Bacchus. The decree applied throughout Italy. Defeated states also often lost land to Rome. Colonies were created in key strategic locations, like tiny Alba Fucens perched up in the Abruzzi to keep an eye on the neighbouring tribes. Other settlers were simply given conquered land to farm in return for paying a rent to the state. Roman control of Italy took the form of a growing network of bilateral alliances, an ever wider distribution of public land and settlers, and an increased sense of the prerogatives of power.

When a Roman army marched out against Samnites or Tarentines, Epirots or Gauls, its general commanded an army composed of citizens and allies.

17

When consuls levied their citizen armies, each allied community was sent orders to provide their own quota of troops. Allied detachments were commanded by their own leaders, and brigaded alongside the Roman forces. Those leaders were drawn from the same sort of propertied classes as ruled Rome: Romans tended to support those classes in allied communities, siding with Greek aristocrats against democrats, and Etruscan nobles against their serfs.

18

The ruling classes of Italian cities had much in common with each other, and a community of interest must also have consolidated Roman power. Athens’s short-lived empire had foundered in part on the promotion of democracy among its lesser allies, and on strengthening the ideology of citizenship: Roman hegemony, by contrast, always stressed class solidarity among the elites. The seeds of an aristocratic empire had been sown. Rome exacted no regular taxes, nor any tribute in kind from its allies: they generally received a share of booty from victorious campaigns, and in some colonial foundations some of the Latins even received grants of land. Perhaps Roman rule did not seem entirely oppressive to members of the propertied classes, more like a movement that benefited those drawn into it.

Pyrrhus and History

King Pyrrhus had ruled the tiny Balkan kingdom of the Molossians since 306

BC

. Macedon had expanded on the margins of the Greek world to produce Alexander, who died in 323

BC

master of the Persian Empire and overlord of most of the Greek world. Pyrrhus’ kingdom was on the margins of Macedonia, and he spent most of his career trying to imitate his great neighbour and predecessor. Epirus corresponds roughly to what is now north-west Greece. It looks westwards, towards the Adriatic, and beyond it to that part of southern Italy known as Magna Graecia (Greater Greece) because of the wealth accumulated there by the Greek cities founded in the archaic period. The Greeks of southern Italy and Sicily had had their own complex history through the archaic and classical periods, fighting wars between each other and against and alongside Etruscans and Carthaginians. During the fifth century some of the Greek cities immediately south of Rome were captured and taken over by peoples from the Italian interior. Lucanians took control of Posidonia around 390 and ruled it for just over a century before Rome took control in 273 and made it into the Latin colony of Paestum. Majestic archaic Greek temples, Lucanian tombs, and a model Roman city stand side by side today.

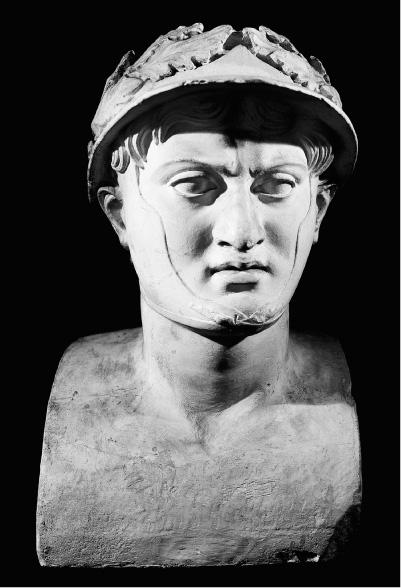

Fig 3.

A bust of Pyrrhus, King of Epirus, Roman copy after a Greek original, from the Villa of the Papyri, Ercolano (ancient Herculaneum), Campania Region, Italy

But in the far south of the peninsula, and in Sicily, the larger Greek cities were more successful. If Rome and Carthage were hegemonic powers, then so were Greek Syracuse and Taranto. It was Taranto which called in Pyrrhus. This was nothing new for them. They had had an alliance with one of Pyrrhus’ predecessors, and had tried to get help from Sparta and others in recent years. The novelty was the enemy, Rome, which in 284 had founded a colony on the Adriatic at Sena Gallica. For Rome, this was an extension of their wars in the Apennines: the name of the colony shows they had their eyes on the Gallic tribes of Marché and the Po Valley. But the Tarentines were right that the Romans had more grandiose ambitions. Two years later they intervened in the affairs of Rhegium, on the toe of Italy, and of Taranto’s neighbour Thurii, leading to direct conflict. No one can have been in any doubt that Rome was extending its hegemony in all directions. Taranto was next.

Pyrrhus’ expedition into southern Italy hardly changed the world. He arrived in 281, and inflicted a couple of defeats on the Romans: he may have won the battles but the cost was so high that it has given us the phrase ‘a Pyrrhic Victory’. He was then invited to Sicily to fight Carthage on behalf of Greek cities there, which he did with less success. Returning to Italy he was defeated by a Punic fleet, and then fought another, less conclusive, battle with a Roman army. Those reverses prompted him to return to Epirus in 275. Pyrrhus was no Alexander. Three years later he was dead, killed in a botched attempt to wrest control of the Greek city of Argos from Macedon. The Romans took Taranto the same year. The significance of the Pyrrhic War, however, was that it put Rome on the Greek map. From this point on, Rome has proper history. One of the Greeks who wrote an account of Rome’s war with Pyrrhus was his contemporary Timaeus, a native of Taormina in Sicily, who spent fifty years in exile in Athens writing the first connected history of the western Mediterranean. That work is lost, but it has left traces in the histories and geographies composed by Greeks and by Romans over the following centuries. Roman history was only a minor part of his output. But so little else had been written that it was a vital source even for the first Roman to write history, Fabius Pictor, and both directly and indirectly also for Polybius, the Greek historian who wrote a continuation during his own exile in Rome. Thanks

to Timaeus and his continuators it is possible, from the third century on at least, to write detailed political history with secure chronology. Thanks to Pyrrhus, the scale of Roman hegemony was now clear across the Mediterranean. Greek cities began to send embassies to Rome from the early second century. Among them were appeals for military help, as Greek cities and Balkan peoples asked the Romans to cross the Adriatic in the opposite direction to Pyrrhus.

Further Reading

Archaeological understanding of the appearance of cities and states in the early last millennium

BC

is progressing rapidly thanks not only to new evidence but also to advances in the way we understand it. The state of the question is presented in a series of essays edited by Robin Osborne and Barry Cunliffe and entitled

Mediterranean Urbanization 800–600

BC

. On the immediate vicinity of Rome see Christopher Smith’s

Early Rome and Latium

(Oxford, 1996). An excellent archaeological introduction to the Etruscans is provided by Graeme Barker and Tom Rasmussen,

The Etruscans

(Oxford, 1998). Guy Bradley, Elena Isayev, and Corinna Riva’s

Ancient Italy

(Exeter, 2007) gives a good sense of the wider Italian world into which Rome expanded.

Tim Cornell’s

The Beginnings of Rome

(London, 1995) is now the standard introduction to early Roman history. Mario Torelli’s

Studies in the Romanization of Italy

(Edmonton, 1995) gives an excellent sense of how archaeological and historical evidence can be effectively combined in the study of this period.

The earliest stages of Roman imperialism are the subject of William Harris’s

War and Imperialism in Republican Rome 327–70

BC

(Oxford, 1979) and of several chapters of John Rich and Graham Shipley’s

War and Society in the Roman World

(London, 1993). Jacques Heurgon’s

The Rise of Rome to 264

BC

(London, 1973) remains full of interesting insights. Jean-Michel David’s

Roman Conquest of Italy

(Oxford, 1996) tells the whole story up to the end of the Republic.

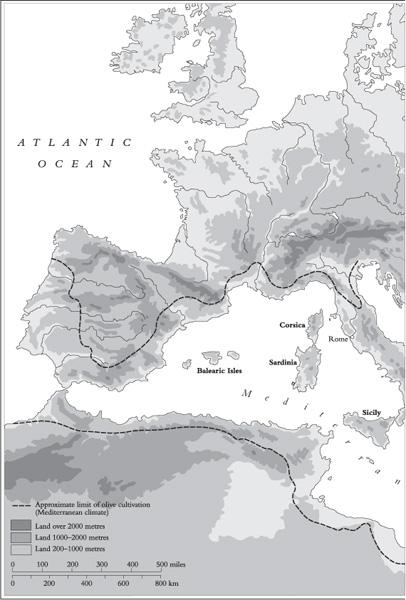

Map 2.

The Mediterranean and its continental hinterlands, showing major mountain ranges and rivers

IV

IMPERIAL ECOLOGY

Next comes the earth, that one part of nature that for her many gifts to us we honour with the name of Mother. She is our realm, as the sky belongs to the gods. She welcomes us when we are born, nurtures us as we grow, and when we are adults sustains us always.

(Pliny,

Natural History

2.154)

From its foundation to the Arab conquests the story of Rome was played out over a millennium and a half. At first expansion was so slow that few outside Italy can have noticed it. But by the reign of Augustus the empire was bounded by the Atlantic to the west and the Sahara to the south, its northern frontier bisected temperate Europe, and its eastern edge was extended deep into western Asia. There the frontiers more or less rested until disintegration began at the end of the fourth century, once again slow at first but eventually collapsing into the Aegean world of seventh-century Byzantium. That fifty-generation tale of rise and fall is an epic one in human terms.