Rome: An Empire's Story (47 page)

Further Reading

Tim Barnes’s

Constantine and Eusebius

(Cambridge, Mass., 1981) is without doubt the best introduction to the complex history of his reign, even if it has not convinced all experts that Constantine was so wholly Christian right from the beginning.

The literature on the rise of Christianity is immense. William Harris’s collection

The Spread of Christianity

(Leiden, 2005) gathers a fine selection of views without

trying to impose one answer. Ramsay MacMullen’s

Christianizing the Roman Empire

AD

100–400

(New Haven, 1984) is a clear account, full of insight. Rodney Stark’s

Rise of Christianity

(Princeton, 1996) has been a good provocation for many historians. Mary Beard, John North, and Simon Price helpfully set Christianity alongside other changes in

Religions of Rome

(Cambridge, 1998). Robin Lane Fox’s

Pagans and Christians

(London, 1986) conjures up the atmosphere of this exciting period better than any other book on the subject.

The implications for the empire and imperial society of Constantine’s decision have generated some of the most innovative scholarship. Peter Brown’s

The Body and Society

(New York, 1988) tracks the emergence of new literatures and practices of asceticism; the accommodation of Christianity and imperial high culture is the subject of Averil Cameron’s

Christianity and the Rhetoric of Empire

(Berkeley, 1991); Dominic Janes’s highly original

God and Gold in Late Antiquity

(Cambridge, 1998) explores how a religion born in poverty came to terms with fabulous riches; Garth Fowden’s

Empire to Commonwealth

(Princeton, 1993) follows the tensions and interplay between religious and imperial universalisms through to the early Middle Ages. Alan Cameron’s

The Last Pagans of Rome

(New York, 2011) is a vivid portrait of the culture, politics, and society of a generation.

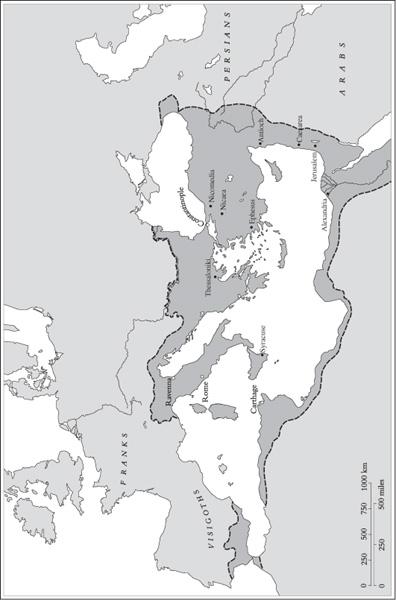

Map 7.

Justinian’s reconquest (

AD

565)

KEY DATES IN CHAPTER XVII

AD | Reign of Justinian |

AD | Roman reconquest of North Africa from Vandals, followed by successful campaigns in Italy to 540 and the invasion of Visigothic Spain in 551 |

AD | Persians sack Antioch |

AD | Beginning of Avar incursions into the Balkans |

AD | Lombards invade Italy |

AD | Reign of Heraclius. Romans lose Jerusalem (614) and Egypt (616) to Persians and on the defensive until Heraclius’ victory at Nineveh in 627 |

AD | Muhammad’s Flight to Medina. The first year of the Islamic calendar |

AD | Constantinople under siege by Avars and Persians |

AD | Roman peace with Persia |

AD | Arab armies defeat Roman forces at Yarmuk. Jerusalem taken in 638, Egypt in 640, and Anatolia invaded in 647. The Persian Empire destroyed in 651 |

AD | Constantinople survives Arab blockade |

AD | Arabs capture Carthage |

AD | Arabs cross the Straits of Gibraltar, invading Visigothic Spain |

XVII

THINGS FALL APART

Let the cities return to their former glory, and let nobody prefer the pleasures of the countryside to the monuments of the ancients. Why avoid in peacetime the very places we fought wars to protect? Who finds anything less welcome than the company of the elite? Who does not enjoy conversing with his equals, promenading in the forum, observing the practice of worthy professions, engaging in legal cases in the courts, or playing that game of draughts that Palamedes loved, or visiting the baths with one’s fellows, or inviting one another to grand banquets? Yet those who choose to spend all their time in the country with their slaves miss out on all of this.

(Cassiodorus,

Variae

8.31.8)

How Empires End

Empires do not all have the same fate. Modern studies of collapse and transformation have failed to establish a single theory of imperial decay, offering instead a range of alternative catastrophes.

1

Perhaps this should not surprise. Empires— even early ones—were complicated engines with many parts that might go wrong. The argument of this book has been that it is persistence and survival that needs to be explained, not decline and fall. Rome’s genius—or good fortune—lay in the ability to recover from crisis after crisis. Until this one.

Some empires succumb to sudden and unexpected violence from without. The empire of the Inka crumbled before the invasion of Pizarro, and the Achaemenid Persian Empire was swept away by Alexander. The rapidity of their fall often seems to follow as much from the demonstration of the fragility of their rulers’ claims to cosmological favour, as from any actual losses in manpower and resources that follow the first reverses. Emperors claim so much. When their weakness is exposed the disappointment is often fatal. Collapses of that sort illustrate how much early empires depended on ideology and symbolism to sustain them.

Other early empires simply fragmented, like the empire of Han China and the Abbasid caliphate. Fragmentation is arguably a risk integral to the structure of tributary empires. Most early empires were, after all, put together when a conqueror accumulated a series of pre-existing kingdoms: Achaemenid Persia and Qin China offer paradigms for this kind of growth. Earlier identities were rarely eroded under the relatively light touch of pre-industrial hegemony and capstone monarchy. Egyptians remembered their pharaohs under Persian, Macedonian, and Roman occupations. Greek writers looked back before Rome and Macedon to the classical age of Athens and Sparta. Even when the issue was not one of ancient traditions, these empires were often composed of separable parts. Tributary empires often simplified their logistics by allowing each region to support its own occupying army and governors. This, too, made individual regions potentially self-sufficient. Alexander’s empire collapsed because it depended on Macedonian armies supplied by local satrapal administration. Fragmentation usually began at the margins. Action at a distance is a problem for all emperors, and distance was exacerbated by primitive communications. A common response was to create powerful border viceroys, lords palatinate, margraves, and the like, with the authority and resources to respond independently to external threats. But when the centre did not hold these border generals often chose to go it alone. The outer satrapies of the Achaemenid and Seleucid empires were often in revolt. Fragmentation may be temporary, of course. Aurelian reunited the Roman Empire, and Antiochus III did the same for the Persian Empire. Chinese imperial history is often presented as an alternation of fragmentation and reintegration.

Yet other empires simply wither away. They lose control of their outer provinces to revolt or conquest, but successfully retrench to their original (or a new) core area. Often their rulers maintained the imperial styles and ceremonies of their grander pasts. Imperial Athens in the fourth century

BC

,

late Hellenistic Syria and Egypt, the last century of Mughal rule in India all offer examples. After the Fourth Crusade resulted in the Frankish seizure of Byzantium in 1204 there remained tiny successor Greek empires in Epirus, Nicaea, and Trebizond. Historical sociologists have never found it easy to distinguish large states from small empires. Perhaps it is best to say that some empires have reverted to ordinary states with extraordinary memories.

During the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries

AD

, the Roman Empire underwent all three of these fates: invasion, fragmentation, and a dramatic downsizing. The empire was repeatedly invaded. I described in

Chapter 15

how Alamanni, Vandals, Huns, and others followed the Gothic groups, who entered the empire in

AD

376. The loss of the western provinces was not as rapid as the fall of the Inka or the Aztec. Yet within a hundred years of the battle of Adrianople, Rome’s Mediterranean empire was no more. There were further invasions during the sixth and seventh centuries. From the north the Avars and Slavs invaded the Balkan provinces and the Lombards Italy. Periodic Persian raids into Syria culminated in 540 in the sack of Antioch. Finally, in the early seventh century, the Arab conquests swept away Byzantine Africa, Egypt, Sicily, and Syria and went on in the next century to destroy Visigothic Spain.

The empire fragmented, too, in the sense that the political unity of the west came apart in stages, leaving intact for a while Roman tax systems, Roman cities, and the Latin-speaking elites who ran both.

2

The fact that taxation was devolved via the praetorian prefectures to the groups of provinces known as dioceses certainly helped make fragmentation feasible. For some Romans in the west, perhaps only the identity of their rulers seemed to have changed.

3

Theoderic the Ostrogoth held court in the imperial capital of Ravenna, celebrated games in the Roman Colosseum and Circus, and patronized the western Senate, even lending some support to efforts to restore the monuments of the city. The Roman senator Cassiodorus had a career at the Gothic court in Ravenna in the early sixth century first as quaestor, then as

magister officiorum

, and finally as praetorian prefect for Italy.

4

These positions, part of the Ostrogothic inheritance from Rome, were among the most senior in the bureaucracy. Like senatorial courtiers of the fourth and fifth centuries, he also interrupted his career for a consulship in Rome. Cassiodorus produced elegant Latin literary works throughout his life, alongside the royal letters he was responsible for drafting. His panegyric of the barbarian king and his (lost) history of the Goths show how easy it was for educated Romans to accommodate themselves to new

circumstances. At the end of his life, he founded a monastery and turned his attention to religious writing. Many of the earlier generation of kingdoms in the west—those of the Ostrogoths and Vandals and Burgundians for example—were in effect hybrid societies; Romans living by one set of laws and performing civil functions while the barbarian leaders lived by their different customs and provided the military. The exact means by which the barbarian ‘guests’ were supported is unclear. Did they own a share of the land? Or have a share of its profits? Perhaps different modes of accommodation were developed in different kingdoms.

5

But it is clear that the kings stood at the head of these societies, tribal leaders and Roman magistrates combined, issuing law and distributing favours to all their subjects. The Visigothic kingdom in Spain preserved elements of this fusion until it was swept away by the Arab conquests in the early eighth century.

At Constantinople, too, some must have taken comfort in the fact that barbarian kings sometimes claimed to rule as subordinates of the emperor and put the eastern emperors’ heads on their coinage. But in practice those emperors had no influence over their appointment, or how they ruled. Mostly they had enough to worry about defending their territory against raids from across the Danube or war with Persia. But fragmentation had been reversed before, and it is not surprising that the eastern emperors did not immediately give up on the west. Most dramatic of all interventions were those of Justinian in the middle of the sixth century. Justinian ruled 527–65 and his reign is exceptionally well documented, most of all by the historical works of Procopius, who produced not only accounts of the emperor’s wars of reconquest and his building activities, but also of the intrigues at court.

6

The great volume of legislation Justinian produced and had codified, and an account of the administration of the empire by one of his praetorian prefects, John the Lydian, together offer a vivid picture of the sixth-century empire.

7

Justinian’s generals succeeded in recapturing North Africa from the Vandals in 533, gaining control of Sicily and much of Italy from the Ostrogoths by 540, and finally creating a beachhead in Visigothic Spain in 551. But the wars in Italy, which were prolonged until 561, exhausted the empire and made impossible the kind of cohabitation between Romans and Goths created by kings like Theoderic and senators like Cassiodorus. The reconquest of Italy was short-lived: in 568 the peninsula was invaded once again, this time by the Lombards.