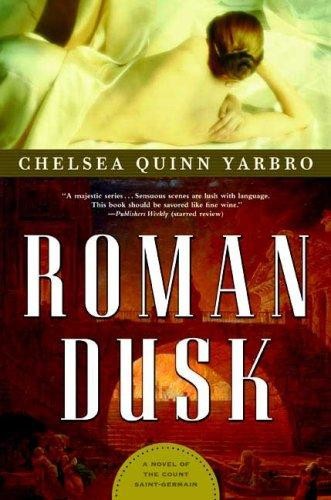

Roman Dusk

Authors: Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

Tags: #Fantasy, #Fantasy Fiction, #Fiction, #General, #Historical, #Horror, #Occult & Supernatural, #Historical Fiction, #Vampires, #Rome, #Saint-Germain

Table of Contents

For

Sharon Russell

,

for hanging in there

Sharon Russell

,

for hanging in there

RAGOCZY GERMAINUS SANCT-FRANCISCUS

T

ext of a letter from Almericus Philetus Euppo, freedman and mercer of Ostia, to Ragoczy Germainus Sanct-Franciscus, foreigner living at Roma outside the walls.

ext of a letter from Almericus Philetus Euppo, freedman and mercer of Ostia, to Ragoczy Germainus Sanct-Franciscus, foreigner living at Roma outside the walls.

To the noble and well-reputed foreigner, Ragoczy Germainus Sanct-Franciscus at the villa that bears his name, to the northeast of Roma, the greetings of Almericus Philetus Euppo, freedman of Ostia, with thanks again for providing half the sum of the purchase prece for the emporium on the Ostia docks where my business stores the cloth I import. May whatever god you worship show you favor, and may no other god act to your detriment.

The Coan linen has finally arrived, on the

Morning Wind

, and all but two of the bales are in fine condition; one of the damaged bales cannot be salvaged, but the other can be, at least two-thirds of it. I have set my slaves to cleaning and blocking the linen to restore it, and I will see to it that the best possible results are obtained, and will provide you a record of what was done.

Morning Wind

, and all but two of the bales are in fine condition; one of the damaged bales cannot be salvaged, but the other can be, at least two-thirds of it. I have set my slaves to cleaning and blocking the linen to restore it, and I will see to it that the best possible results are obtained, and will provide you a record of what was done.

You are fortunate to have so many of your ships reach port unscathed, and the cargos damaged by nothing more than weather. True, shipping has increased steadily over the last few years, which would ordinarily be cause for rejoicing, but with this increase in commerce has come increase in theft of all sorts. You may not be aware of how piracy has increased over these last few years, but most merchants have seen their losses to pirates and pilferage double since the end of the reign of Caracalla and the present, unpromising tenure of Macrinus. Reducing the pay of soldiers would appear to be a false economy to me in these times, but as Caesar, he has the right to do it, and those of us who must bear the brunt of his decision in loss of merchandise and higher taxes can only hope that he will not ruin us and leave us unguarded as well.

I do not mean to alarm you, but because of these changes in the Legions and the navy, I would advise you to consider carrying armed men on your merchant ships in future, to avoid losses to the pirates. I am enclosing a bid for your entire shipment, which I think you will find is more than fair in the current marketplace. I can supply you a letter of authorization, or funds in coin, as you prefer. The coins tend to attract more attention from footpads and other criminals, but there is a certainty in coins that cannot be denied.

According to my roster, you have three more ships due into port this month: the

Neptune’s Pride,

the

Northern Star,

and the

Song of the Waves.

I have nothing to report on any of these vessels, nor any of your others not yet bound for Ostia and home from any ship arrived in Ostia in the last week. I will have my scribe copy out the account provided by your captain, Getus Palmyrion, to enclose with this letter. He says the passage was relatively easy, given the time of year and the general condition of his crew and oarsmen. Again, you are fortunate to have so worthy a captain, who is alert to the needs of his men. Two days since, a ship of Pompeianus Dritto arrived with nine oarsmen suffering from fever, and half the crew also ill. They said they had taken on bad water in Tarrraco, and that the sickness came upon them at sea. Whatever the cause of their ailment, the ship and its crew and oarsmen have been isolated, and they will remain so until all have recovered or died. No amount of bribes or favors owed will change their situation; only convicted criminals are used to take food and water to the ship.

Neptune’s Pride,

the

Northern Star,

and the

Song of the Waves.

I have nothing to report on any of these vessels, nor any of your others not yet bound for Ostia and home from any ship arrived in Ostia in the last week. I will have my scribe copy out the account provided by your captain, Getus Palmyrion, to enclose with this letter. He says the passage was relatively easy, given the time of year and the general condition of his crew and oarsmen. Again, you are fortunate to have so worthy a captain, who is alert to the needs of his men. Two days since, a ship of Pompeianus Dritto arrived with nine oarsmen suffering from fever, and half the crew also ill. They said they had taken on bad water in Tarrraco, and that the sickness came upon them at sea. Whatever the cause of their ailment, the ship and its crew and oarsmen have been isolated, and they will remain so until all have recovered or died. No amount of bribes or favors owed will change their situation; only convicted criminals are used to take food and water to the ship.

I have a roster to send to you, from your colleague, Rugeri, from your emporia in Alexandria in Egypt, along with a sealed chest. According to what Getus Palmyrion has told me, it is a gift from a group of ancient priests who occupy some of the huge ruins near Luxor. The volumes from Rugeri are with the gift, as is his pouch of (untouched) aurei, your portion of the seasonal profits of your business in Egypt, along with his admonition to treat the carved wooden container with care. The roster is in a leather satchel and the casket from the priests is bound with lead, which will keep everyone out but those who can break or melt the lead. I have added wax and my seal to the lock on the satchel to indicate that it was undisturbed when it left my hands. If the seal is broken you will know there is a good possibility of tamperage, in which case, I recommend you notify the authorities about the crime.

It is my understanding that the spice-and-dye merchant Tercius Fortunatus Perusiano is going to send you an offer on that part of the

Morning Wind’

s cargo. If you will be advised by me, you will wait until Petros Demetrianos has had a chance to make a bid, for he has had a recent increase in fortune and is in a position to offer you more than Perusiano will—Perusiano has a daughter about to marry, and he has had to endower her handsomely, and to take his pledged son-in-law into his business, all of which has left him with depleted funds.

Morning Wind’

s cargo. If you will be advised by me, you will wait until Petros Demetrianos has had a chance to make a bid, for he has had a recent increase in fortune and is in a position to offer you more than Perusiano will—Perusiano has a daughter about to marry, and he has had to endower her handsomely, and to take his pledged son-in-law into his business, all of which has left him with depleted funds.

Perhaps I should mention that an interesting object has arrived here, brought from a port beyond Byzantium: a very ancient sarcophagus, from the eastern crest of the Carpathian mountains. The claim is that is belongs to an ancient people, long vanished from the region, who, like the Etruscans of old, made carvings of the inhabitant of the sarcophagus as that person was in life—playing, dining, counting wealth, drinking, engaged in passion—instead of the repose of death. This particular sarcophagus depicts a man propped on his elbow and polishing a wide-bladed sword. He is smiling, and his upper leg is cocked. Knowing your interests in things from that region, I have made a bid upon it. If you wish me to pursue the matter, send me word how much you will authorize me to spend, and I will attempt to secure this object for you and have it carried to you by ox-cart, escorted, of course.

As soon as another shipment of cloth reaches my establishment here in Ostia in one of your ships, I will, as always, notify you at once, and send word by my own courier, as I have done in this instance. I intend to use my own couriers for business purposes from now on, and to send them along with at least one guard for escort. An extra expense, yes, but worth ever denarius if the messenger is protected along the way. There are many soldiers willing to hire out as escorts just now, and I recommend securing the services of a few for your couriers.

Melidulci in the lupanar has ordered nard and perfumed oils for her new establishment, and has brought in ten new girls. She has offered to receive you and any of your associates at any time you wish to call upon her. Apparently she is grateful to you for providing some medicaments to her when many of the women of the lupanar were taken with the fever of bad air, and could not work. It is always wise to have the good opinion of the women of the lupanar, is it not?

I hope you have become accustomed to Roma again, and that the demands of your move to your villa have not proven too exhausting to your body, your spirit, or your purse. There are as many drawbacks as advantages in being so close to the center of power, but, as you have lived there before, or so you said, your accommodation of Roman ways should not intrude upon you too much. Thus far, our dealings have been pleasant and profitable to us both, and I hope that they may continue to be so.

Almericus Philetus EuppoFreedman and mercer of Ostia

by my own hand on the 7

th

day of March in the 971

st

Year since the Founding of Roma: with enclosures and parcels to accompany this

th

day of March in the 971

st

Year since the Founding of Roma: with enclosures and parcels to accompany this

Clouds clotted the morning sky over Roma, their shadows bruising the buildings in their passing. In the Forum Romanum, such things were ignored; the Forum was alive with farmers driving their animals to the market-stalls just beyond the impressive buildings, their hogs, calves, sheep, goats, and stacked cages of chickens ready for sale. All manner of customers, from well-born women in sedan chairs accompanied by slaves to young men of rank in bigae, their horses on show as much as they themselves, to shopkeepers’ wives selecting the meat for prandium, as well as Praetorian Guards, minor politicians, idlers from the baths, the curious, entertainers, speakers of all kinds, a handful of foreigners in outlandish clothing, a sprinkling of criminals and petty gamblers, slaves, and those with business to do added to the noisy confusion. The babble was loud, enhanced by the marble walls of the buildings surrounding the Forum.

Ragoczy Germainus Sanct-Franciscus strolled the edge of the Forum, his double-woven black trabea and high Persian boots in red leather marking him as a foreigner as much as the winged pectoral device he wore on a collar of heavy silver links. His dark, wavy hair was cut fashionably, and his beard was short and meticulously trimmed; he squinted in the occasional bursts of light, all the while trying to keep clear of the milling crowd. “The Swine Market is always—”

“Chaotic? Overflowing?” asked his companion, Septimus Desiderius Vulpius. “I could not agree more.” He was in a good mood, enjoying himself and anticipating better to come; his toga virilis was a fashionable terra-cotta color, complementing his red-blond hair and short beard. Around his neck on a braided leather thong he wore a small silver sandal with wings, evoking the help of Mercury in todays endeavors. At twenty-nine, he was the head of his own household, well-married to Filomena Dionesia Crassens, Domina Vulpius, the father of three healthy children, and finally coming into the fortune of his uncle, which had been left to him as his uncle’s only heir. In spite of everything, he thought, life was good.

“Dynamic,” Sanct-Franciscus amended. “And filled to capacity. Still, it is exciting, and apparently removed from all the other problems that have weighed so heavily upon the city.”

“And the Empire; our borders are beleaguered, you mustn’t forget,” added Vulpius, not willing to let these misfortunes mar his day.

“Yes. The Empire has not had an easy time of it,” agreed Sanct-Franciscus, stepping around a group of youngsters engaged in an improvised cockfight; the two combatants were ruffling their feathers and making their first sallies at each other, to the noisy approval of their audience.

Vulpius looked around uneasily. “Caracalla did much damage.”

“Yes, he did,” said Sanct-Franciscus, thinking that Macrinus might not prove much better at ruling the Roman Empire than Caracalla had been.

“The Senate is divided and has done nothing to help the people,” Vulpius declared.

“That is hardly surprising, given the tenor of the times.” Sanct-Franciscus glanced around him at the impressive public buildings. “What would you expect the Senate to do?”

“I don’t know,” Vulpius admitted. “But for most Romans, the choice of Caesar is out of their hands, as it is out of so many.”

Glancing at the marketplace again, Vulpius added, “And no matter who is Caesar, people need to eat.”

“That they do; and judging by the crowds at the market, they will,” said Sanct-Franciscus, and started up the stairs to the massive building where the law courts of the city were currently held, the Basilica Julia, distinguished by its triple colonnade and slightly old-fashioned facade.

“This should not take long; the decuriae have to earn their keep, I suppose,” Vulpius said, a touch of nervousness pinching his voice.

“I have the commoda,” said Sanct-Franciscus, indicating the wallet that hung from his broad belt of black leather.

Vulpius forced a laugh. “It is the merest formality, you know, for his Will was recorded four years ago without qualifications, while my uncle was still alive to endorse all the terms in it. My father-in-law vouched for it before his death.”

“As you say, it is a formality,” Sanct-Franciscus said calmly, nodding to the footman who stood by the door of the building to remind all those arriving to cross the threshold with their right feet. The interior was impressive, the lobby rising three stories above them at the back of the long, triple row of columns, galleries on each floor joined by wide staircases. It was as busy a place as the Forum outside, but without the livestock, and it roared like the sea from the echoes of conversations.

Vulpius went inside right foot first, and smiled. “Our success is assured.”

“I had never any doubt,” said Sanct-Franciscus, looking along the long lobby to the first corridor, noticing that although the people within the Basilica Julia were busy, there were fewer of them than he had expected. “It is the third door on the left, I believe?”

“So I was told,” said Vulpius.

“Then ‘the sooner begun, the sooner ended,’” Sanct-Franciscus reminded him. “Do you agree?”

“That old aphorism has haunted me most of my life,” Vulpius admitted as he tagged after Sanct-Franciscus.

They reached the door and looked for the slave to admit them, but no one was in place to tend to that courtesy. Sanct-Franciscus made a quick scrutiny of the corridor, then shrugged. “Shall we knock?”

“I suppose we’d better,” said Vulpius, and reluctantly tapped on the door. He paused and repeated the summons.

The door opened a bit, revealing a dark, wrinkled face and a slave’s collar. “Your pardon, Citizen of Roma. I forsook my post.” He lowered his head as if for a blow.

“If you will admit us, there is no harm done,” said Sanct-Franciscus before Vulpius could speak.

“Certainly, certainly,” said the slave, his accent identifying him as a native of Carthago on the north coast of Africa as much as the color of his skin. “Mind your step.”

Again Sanct-Franciscus and Vulpius crossed into the room on their right feet, and Vulpius looked around, noticing the low rail that bisected the chamber, with the three writing tables on the far side of the rail. Just at present, no one occupied the tables, and that struck Sanct-Franciscus as odd, and he was about to mention this to Vulpius, when he spoke. “I am expected. Septimus Desiderius Vulpius, heir of Secundus Terentius Vulpius.”

“You are expected?” the slave repeated, sounding puzzled; before Vulpius could answer, “You received a notice from this office?” the slave pursued.

“Yes. I have it with me, if you need to see it, along with my copies of the Will and letter of disposition,” said Vulpius, his increasing tension making him haughty.

“No, that is hardly necessary. I shall inform Telemachus Batsho that you are here,” said the slave. “If you will remain in this room?”

“Certainly,” said Vulpius. “I am more than willing to wait.”

“No need to be nervous,” said Sanct-Franciscus in a lowered voice as the slave left them, going through a small door near the far wall. “This is only a matter of form. The Senate upheld the Will and there is just the matter of recording the transfer of titles. This man Batsho is simply a clerk with an elegant title, and an expectation of commoda for his service.”

“I know; I know,” said Vulpius, snapping his fingers.

“So you need not fret.” Sanct-Franciscus held up his hand.

“Truly,” said Vulpius with a transparent lack of conviction.

“You, yourself, Desiderius, have said that all is settled,” Sanct-Franciscus reminded him; he decided not to mention the absence of clerks, assuming that the afternoon recess began early in these offices, an increasing practice in the law courts of Roma.

“No doubt,” said Vulpius, and shook his head. “Pay no notice to me. I am in a state of anxiety, as you say. I am often thus when dealing with officials, even petty ones like this decuria.” He cleared his throat and touched the silver winged sandal talisman. “It will pass as soon as our waiting is ended.”

“Very good,” said Sanct-Franciscus, and went to the nearest bench where he sat down patiently.

Vulpius began to pace, whistling softly and tunelessly between his teeth. “It was generous of my uncle to provide so well for me.”

“You are his heir. It is fitting,” said Sanct-Franciscus.

“My father would agree; he was the elder brother, which is why his wealth was seized by Caracalla. Fortunately, my uncle was left the vineyards, and flourished when my father was removed from office and exi—Never mind. I’m babbling, and you’ve heard this before.” Vulpius sighed. “I will have to assume responsibility for my two cousins, of course.”

“You knew you would have to,” said Sanct-Franciscus, thinking of the many discussions he and Vulpius had had on this point since January, when the Will was upheld.

“I should do my best to find husbands for them, and dower them as my uncle would have wished. I know what my responsibilities are toward them.” Vulpius was talking as much to himself as to Sanct-Franciscus. “They will want to marry, don’t you think?”

Sanct-Franciscus thought back almost two centuries to the time when women owned property in their own right, requiring no husband, father, brother, or son to control their money and lands. When the first change had come, Sanct-Franciscus had received a flurry of outraged letters from Atta Olivia Clemens, upbraiding the Senate for depriving the women of Roma of their autonomy, and predicting that this would not be the last erosion of women’s position in Roman law. “I would suppose your cousins would want to have access to their legacies however it may be accomplished.”

Vulpius laughed, the edgy echoes lingering in the room. “Husbands protect their wives and daughters. That is expected. Juliana and Caia deserve the care marriage will make possible.” He paced another dozen steps. “A pity my uncle chose to keep them with him for so long.”

“How old are they?” Sanct-Franciscus asked.

“Juliana is twenty-three and Caia is twenty; they’re pretty enough and not overly clever. Not too old, either, but far from as young as many men prefer their wives to be. They like to live in the country, so I do not have to house them with my family; that might be difficult, given the plans Dionesia has for our children.” Vulpius rocked back on his heels, the thongs of his sandals groaning with the strain. “Fortunately, my daughter is still too young for such arrangements, although Fulvius Eugenius Cnaens has spoken to me of the possible union of Linia to his son Gladius.”

“How old is Linia?” Sanct-Franciscus pictured the child in her tunica and palla, hair tangled, running through the Vulpius’ house.

“Nine; I have permitted her until eleven to decide for herself,” said Vulpius. “The contract cannot be settled for another two years, of course, but—” He broke off as the slave returned.

“Telemachus Batsho will be with you in a moment, and bids me tell you that he will not delay you very long. He is looking for the documents you will need to sign and seal.” The slave was apparently impressed with Batsho’s importance, for he lowered his head respectfully as he spoke Batsho’s name.

Almost without thought, Vulpius fingered the cylinder ring on his index finger. “I am ready.”

“Very good,” said the slave. “And your companion will serve as witness?”

“I will,” said Sanct-Franciscus.

“You are a resident foreigner owning property in Roma?” The slave rattled off the question in a manner that suggested he had asked such things many times before.

“Not within the walls, but three thousand paces beyond them,” said Sanct-Franciscus. “I, and those of my blood, have held the land since the days of Divus Julius. Many generations.”

“Hardly a god, was Gaius Julius,” muttered the slave; then, more loudly, “A goodly time. Two centuries, at least.”

“So I have reckoned,” said Sanct-Franciscus.

“The new law will not allow you to reside at your estate if it is outside the walls of the city. By the end of summer, you must have a residence within the walls or your lands beyond them will be subject to partial confiscation,” said Batsho smugly as he came into the room. He made his gesture of respect in an off-handed way, with no attempt to hide his sizing up of the two men before him.

“A little more than a year ago the Roman state almost took my land because I was living in Egypt and ordered that I reside on my Roman lands for three years out of five in order to keep them,” Sanct-Franciscus told the decuria. “I have complied with that order, have I not?”

“This is a honing of that provision,” Batsho said in a manner that closed the subject.

Vulpius stepped closer to the slave. “Is there a problem? I was informed he is a satisfactory witness.”

“That he is, so long as there is record of his property and his family’s claim to it.” The slave moved back from Vulpius.

Telemachus Batsho had been one of the decuriae for nearly a decade and was growing comfortably rich on the commodae he received for doing his job. He was a very ordinary man, in a very ordinary sage-green pallium, with a soft belt of braided, multi-colored wool, and two leather wallets attached to it, one for food and money, one for the badge of his office. His hair was a bit longer than fashion, of a medium-brown color that almost matched his eyes, and he was clean-shaven. He nodded to Vulpius and Sanct-Franciscus, saying as he did, “I believe you have had notification of these signings? I recall that a notice was dispatched to you? Do you have it with you?”

Other books

Shadowed (Dark Protectors) by Rebecca Zanetti

Madison's Music by Burt Neuborne

The Dark Horde by Brewin

Blown by Chuck Barrett

The Mammoth Book of Erotic Confessions by Barbara Cardy

Murder on the Candlelight Tour by Hunter, Ellen Elizabeth

Element, Part 1 by Doporto, CM

Boy, Snow, Bird by Helen Oyeyemi

Freefall (The Indigo Lounge Series, #5) by Zara Cox