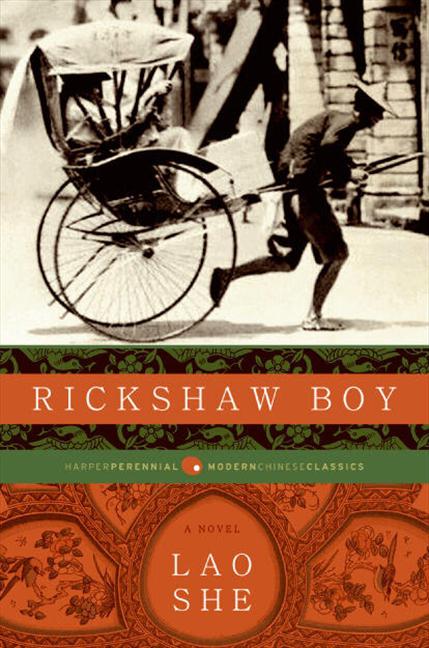

Rickshaw Boy: A Novel

Rickshaw Boy

A Novel

Lao She

Translated by Howard Goldblatt

Contents

I’d like you to meet a fellow named Xiangzi, not…

Xiangzi’s happiness buoyed him; with a new rickshaw, he ran…

Xiangzi had run twenty or thirty steps when he stopped.

Xiangzi was laid up for three days in a little…

As promised, Old Man Liu told no one of Xiangzi’s…

An early autumn night, with breezes rustling leaves that cast…

Xiangzi moved into the Cao home.

Mr. Cao had the rickshaw repaired and deducted nothing from Xiangzi’s…

Xiangzi was barely able to step across the threshold. In…

Xiangzi was not smart enough to deal with his problems…

After the encounter with the old man and his grandson,…

Xiangzi was looking for a place to sit down and…

The sky seemed to lighten a bit earlier, thanks to…

The Liu birthday celebration was a roaring success, and Fourth…

Since Xiangzi was not capable of hitting an old man…

Xiangzi’s period of idleness lasted till the fifteenth day of…

Little by little, Xiangzi pieced together what had happened at…

By June the compound was silent during the day. The…

Xiangzi lay in a daze for two days and nights.

Xiangzi sold his rickshaw.

When chrysanthemums came on the market, Mrs. Xia bought four pots,…

Xiangzi had forgotten where he was headed as he strode…

Xiangzi walked down the street, shaken to the core, when…

Another season for pilgrims to burn incense at mountain temples…

About the Author and the Translator

L

ao She (Shu Qingchun, 1899–1966) remains one of the most widely read Chinese novelists of the first half of the twentieth century, and probably its most beloved. Born into an impoverished Manchu family—his father, a lowly palace guard for the Qing emperor, was killed during the 1900 Boxer Rebel-lion—he was particularly sensitive to his link to the hated Manchu Dynasty, which ruled China from the mid-seventeenth century until it was overthrown in 1911. The view of one of his biographers is difficult to dispute: “The poverty of his childhood and the fact that these were also the years when the dynasty was collapsing and the Manchus were becoming a target of increasingly bitter attacks left a deep shadow on Lao She’s impressionable mind and later kept him from personal participation in political activities. But his alienation strengthened his sense of patriotism and made his need to identify with China even more acute.”

*

After graduating from Beiping Normal School, Lao She spent half a dozen years as a schoolteacher, primary school principal, and school administrator. Then, in 1924, after joining a Christian society and studying English, he accompanied a British missionary, Clemont Egerton, to London, where he taught Chinese at the University of London’s School of Oriental Studies. Among his lesser-discussed activities there was the acknowledged assistance to Egerton in his translation of the “indecent” classical novel

The Golden Lotus

, in which the racy parts were rendered in Latin. During his time away from the classroom, Lao She read voraciously. He has written of his fascination with British novels, in particular the work of Charles Dickens, whose devotion to the urban downtrodden and use of ironic humor Lao She found particularly affecting; they would inform much of his own work, particularly the early novels and stories.

Lao She’s literary career began during his five-year stay in England, where he wrote three novels:

The Philosophy of Lao Zhang

(1926), a mostly comical look at middle-class Beiping residents and modeled, in the author’s own words, after

Nicholas Nickleby

and

The Pickwick Papers

;

Zhao Ziyue

(1927), a generally unsympathetic exposé of the activities of a group of college students; and

The Two Mas

(1929), the tale of a Chinese father and son living, and loving, in London. All three were serialized in China’s most prestigious literary magazine of the day,

Short Story Magazine

, before Lao She returned to China, in 1929, after a six-month stop in Singapore, where he taught Chinese in a middle school; there he wrote most of a short novel,

The Birthday of Little Po

(1931), the only one of his novels that focuses entirely on a child, a Cantonese boy living in Singapore.

Upon Lao She’s return to China, he landed a teaching job at a Shandong university, where he continued to write and publish. His first novel written there,

Lake Daming

(1931), was set to be published in 1932, but the author’s only manuscript was lost when a Japanese bomb destroyed the publishing house. Later in 1931 a dystopian satire set on Mars entitled

Cat Country

(1932) appeared, followed closely by

Divorce

(1933),

*

a tale of domestic strife. Taken together, the two novels give witness to Lao She’s increasing dejection over deteriorating social and political conditions in China and the rise of nationalistic, even revolutionary, tendencies throughout the country in the wake of the Japanese occupation of Northeast China (Manchuria) in 1931, with the establishment of the puppet state of Manchukuo, followed by a Japanese attack on Shanghai the same year.

While

Cat Country

and

Divorce

broaden the author’s critique of the weakness of the Chinese character, castigating it as a malaise that affects the whole nation, not just pockets of middle-class urbanites, Lao She continued to see the salvation of Chinese society in the Confucian ideal of individual moral integrity, the vaunted

junzi

, a man of virtue. This begins to change with the slight novel

The Biography of Niu Tianci

(1936),

†

in which the author entertains doubts that “individual heroism could be of any use in a generally corrupt society.”

‡

Lao She’s political ambivalence had begun to give way to more active political engagement. The bankruptcy of individualism in the face of a corrupting and dehumanizing social system is both the political and moral message of his next novel,

Rickshaw Boy

, which was first serialized in a magazine edited by Lin Yutang,

Cosmic Wind

(1936–1937), and published as a book in 1939; it has been republished many times in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and in Chinese communities in the West.

Not only had Lao She matured as a writer when he wrote

Rickshaw Boy

, but he also had finally been able to quit teaching, a job he admitted he did not like, and devote all his time and energies to his craft. The polished structure, language, and descriptions of this complex novel made for a fitting debut as a full-time writer. After producing a series of novels that dealt with middle-class urbanites, minor officials, college students, and the like, in

Rickshaw Boy

, Lao She chose an illiterate, countrified common laborer as the vehicle for his ongoing social critique. Though a case can be made for viewing the novel as an “allegory of Republican China” in which “the Chinese people were bullied by imperialist powers, misled by the false promise of capitalist modernization, and betrayed by corrupt government, miscarried revolution, and their own disunity,”

*

at its core it “portrays the physical and moral decline of an individual in an unjust society”

†

and, for the first time, hints at a way out: a move away from individualism and toward collective action. Lao She himself wrote of the novel in 1954, “I expressed my sympathy for the laboring people and my admiration of their sterling qualities, but I gave them no future, no way out. They lived miserably and died wronged.”

‡

For a twenty-first-century reader who knows how things have turned out in China, the novel can be read as commentary on the sorts of struggles the underprivileged of the world face daily and the powers that keep them that way. It is also a stark but edifying picture of the early-twentieth-century city in which Lao She was born and died.

During the war years (1937–1945), Lao She spent most of his time in the interior, where he devoted his energies and lent his patriotic zeal to the publication of anti-Japanese magazines and to the chairmanship of the All-China Association of Resistance Writers and Artists. There he began a novel set in one of Beijing’s traditional quadrangular compounds,

Four Generations Under One Roof

, which he would not finish until several years later. He did start and finish a novel—

Cremation

—which he considered to be an utter failure, owing primarily to a lack of understanding of life in areas under Japanese occupation: “If a work like

Cremation

had been written before the war,” he wrote, “I would have thrown it into the wastepaper basket. But now I do not have that type of courage.”

*

For a variety of reasons, not least of which were the demands upon writers to serve the war effort, Lao She’s major achievements during this period were in patriotic plays, most of which were forgotten after the war. It is important to keep in mind that during these troubled times, when the Japanese invasion was further complicated by the irreconcilable strife between Communist and Nationalist forces, and the continued presence of warlords, particularly in the north, Lao She was the only cultural figure who commanded enough respect by all sides to serve in a leadership role of patriotic literary and art associations.