Richard The Chird (14 page)

Authors: Paul Murray Kendall

Edward went first to St. Paul's to make an offering. He halted briefly at the Bishop of London's palace to see that Henry VI and his smooth-tongued keeper, the Archbishop, were packed off safely to the Tower. Then he rode to Westminster, and pausing only long enough to utter a brief prayer and let the Archbishop of Canterbury touch the crown to his brows, he strode into the sanctuary. . . .

The kyng comforted the quene and other ladyes eke,

His swete babis full tendurly he did kys,

The yonge prynce he behelde and in his armys did here.

Thus his bale turnyd hym to blis; Aftur sorow joy, the course of the worlde is. The sighte of his babis relesid parte of his woo; Thus the wille of God in every thyng is doo. 29

When Edward brought his wife and children to Baynard's Castle, the old Duchess of York's house on the bank of the Thames, Richard and George of Clarence completed the family reunion.

Next day, Good Friday, Richard attended a great council of war and afterward looked to the supplies and equipment of his men. Stout warriors came in to the King's aid: Lord Howard, a brother of Lord Hastings, and Sir Humphrey Bourchier and his brother leading a troop of Kentishmen. The best news of all, however, came from the scouts, who reported that the Earl of Warwick was approaching the city with all his forces. One of the principal reasons Edward had marched for London was to tempt Warwick to battle before Queen Margaret and the Bastard of Fauconberg arrived.

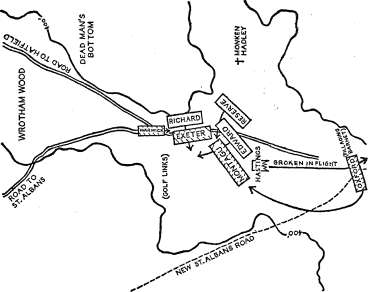

At midday on Easter Eve the royal captains—Richard of Gloucester, George of Clarence, Lord Hastings, Earl Rivers, Lord Howard, Lord Say—mustered the army in St. John's Fields under Edward's eye. Scouts brought fresh tidings that Warwick had taken the Barnet road out of St. Albans. As Edward's chief commanders took up their stations in marching order, the throng of citizens who were watching must have been startled. The ever-faithful Lord Hastings commanded the rear guard; the King himself, assisted by Clarence—well to keep an eye on Clarence—led the center wing; but the critical charge of commanding the van Edward had bestowed upon his brother Richard, who was but eighteen years old and had never fought a major battle. 30

Barnet*

. . . the arbitrament Of bloody strokes and mortal-staring war

AT FOUR o'clock in the afternoon Edward ordered his army /A to set forth, taking King Henry with him for safekeeping. -* *• As it grew dark, Richard was leading the van of the host up the long hill toward Barnet, ten miles north of London. A messenger reported that Edward's "afore-riders" had collided with Warwick's "afore-riders" in Barnet, had driven them from the town, and were pursuing. By the time Richard entered Barnet, perched on the southern edge of a great plateau four hundred feet above sea level, the Yorkist scouts were pouring back into the town from the St. Albans road; Warwick's whole army lay not more than a mile ahead, astride the road, and sheltering behind a thick line of hedges. Halting his men in the town, Richard sent word to the King, who soon galloped up to survey the situation. It was now full night, but after a brief conference with his commanders, Edward decided to press forward. Under cover of darkness the army was to form a line so close to Warwick's host that the Earl must needs fight on the morrow. It was an exceedingly difficult maneuver, which reveals the King's confidence in his captains and his men.

Bidding his troops to show no lights nor make undue noise, Richard warily led them several hundred yards up the St. Albans road and swung off to the right on to the treeless, heathery flat which is now the placid park of Hadley Common. While he and his officers struggled in the dark to form a line, King Edward was bringing his center into position astride the road, and finally Hastings, turning off to his left, extended his wing along the western slope of the plateau. Richard and his men could hear, somewhere ahead of them, the thousand noises of a great host. To their

107

RICHARD THE THIRD

left sounded the intermittent boom of Warwick's cannon. Aware that the King's army had approached, the Earl "shot guns almost all the night, but . . . they always overshot the King's host, and hurted them nothing, and the cause was the King's host lay much nearer them than they deemed." 1 To keep his position hidden, Edward refrained from replying with his artillery. Like the other commanders, Richard strove to settle his men for the night as quietly as possible. Soldiers stretched out on the damp ground to get what sleep they could—men-at-arms in their iron harness, archers in padded leather "jacks." A dense mist began to roll up from the valleys and settle over both the hosts, making armor clammy to the touch, muffling sounds.

By four o'clock in the morning of Easter Sunday, Richard's captains had waked their men. Grimly munching the cold meat they had brought with them in their wallets, they moved with stiff joints into their positions of battle. Like Edward and Hastings, Richard had placed on each flank a clump of archers. Between them stretched a line of dismounted men-at-arms. Even the greatest lords, and the King himself, fought on foot, cavalry being used only to reconnoiter or pursue. 2 An opaque, watery grayness proclaimed the coming of dawn. Thick fog blanketed the field Though it was impossible to see ten yards, the King's trumpets suddenly sounded the alert. Richard ordered his archers to fire blindly. Cannon boomed up and down the line. Beyond the wall of mist, Warwick's trumpets replied.

As Richard was discovering that no enemy fire of arrows or artillery came from before his front, Yorkist trumpets sounded again. His test was upon him. He lacked the physique to be a warrior, the experience to command an army corps, and the eloquence of a Clarence to stir the imagination of followers. For two years he had actively shared Edward's turbulent history, and Edward, appraising what his young brother had accomplished, had now given the precious right wing of the host into his hands. He owned only the hard-won resources which his will had forged, and whatever he had learned of the ways of battle, and his courage.

The slight and youthful Duke of Gloucester tersely gave his captains the word to advance banner,

<

I

8-

HO RICHARD THE THIRD

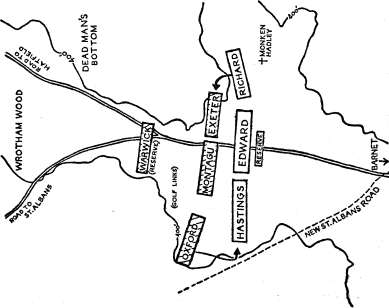

With his squires at his side and his household knights gathered about him, he led the royal vanguard forth through the mist to close with the enemy. To his left he heard a crash of steel as two lines of fighting men collided. But still he encountered nothing except an endless milk-gray opacity. Only when he found himself advancing down a steep slope into marshy bottom land did he realize why he had met no resistance. Warwick must have anchored his left wing on the edge of the plateau overlooking this bottom. In the darkness Richard had far outflanked the enemy's position.

Hurriedly he and his captains swung the line about so that it headed west instead of north. Up the slope Richard and his men clambered. With a shout they burst onto the plateau and fell upon Warwick's flank. The Lancastrians recoiled. Confusion spread down their line. Up from the bottom the Yorkists continued to swarm. But the going was laborious and slow for men encased in steel. By the time Richard had enough men to establish a foothold, the enemy captains had been able to make a new front running north and south. Heavy reinforcements streamed out of the mist to bolster them.

Richard was in the thick of the conflict, swinging a battle-axe. One of his squires went down. 3 * The numbers of the enemy swelled. At intervals his household warriors closed a steel wall in front of him so that he could consult with his captains. On either side of him the writhing battle-line faded away into the fog. His men were outnumbered now. The Lancastrian reinforcements were pressing hard to hurl his whole wing from the plateau. Desperately Richard and his men struggled to hold their positions. The issue was doubtful in the extreme.

Warwick had brought fifteen thousand men to that field, adherents of the Nevilles and Lancastrians cheek by jowl. The Duke of Exeter commanded the left wing, which was stationed between the St. Albans road and the marshy hollow today called Dead Man's Bottom. Montagu held the center, the bulk of which extended west of the road; the Lancastrian Earl of Oxford, the right wing. It was Oxford's men who were sheltered by a line of hedge,

BARNET

perhaps the same which can still be discerned running northwestward across a golf links to the new Barnet-St. Albans road. Warwick took up his command post with the reserve. Though this host outnumbered the King's forces, probably by a third, it had been stung by Edward's unopposed march through the realnf, oppressed by the loss of London, and infected with doubts by the treachery of Clarence and the ambiguity of Montagu. Yet many of these men must have come to the field like Sir John Paston and his younger brother, with right good hope of victory. The Pastons were fighting not out of loyalty to King Harry or intense political conviction, but because the Earl of Oxford had taken their part against the Duke of Norfolk; and doubtless it was such local ties and special interests that drew many of the combatants to the heath north of Barnet on this fog-wrapped Easter Sunday. 4

When the Duke of Exeter discovered that a strong force, storming out of the marshy hollow, had thrown his flank into disorder, he dispatched an alarming message to Warwick; and as he labored to form a new line he sent further urgent appeals for help. Warwick, nervously jumping to the conclusion that Edward had thrown the bulk of his army into this surprise attack, hurriedly committed most of his precious reserve to the Duke. He was soon relieved to learn that Exeter's line was now holding, and in a moment he received glowing good news.

Like Richard, the Earl of Oxford had discovered that his right wing far outflanked the enemy; but unlike Richard's, his men had easy going. They swung eastward, crashed into Hastings' flank and began to roll up his line. Most of Hastings' wing was swept away. With the Earl himself at their head, the Lancastrians pelted toward Barnet in hot pursuit, poured into the town, and began plundering. Some of the Yorkists, finding horses, fled all the way to London, crying that the day was lost and King Edward and his two brothers slain.

The rank and file of the King's army were not disheartened, however, for the mist providentially hid this disaster from them; and Hastings managed to form the wreck of his wing into a front

RICHARD THE THIRD

to hold off the right side of Montagu's center. Richard's flank attack and the collapse of Hastings' force had wrenched the battle line about so that it now ran roughly north and south. 5

In the center of the field the fighting raged fiercely. The King himself "valiantly assailed [his enemies], in the midst and strongest of their battle, where he, with great violence, beat and bore •down afore him all that stood in his way, and, then, turned to the range first on that one hand, and then on that other hand, in length, and so beat and bore them down, so that nothing might stand in the sight of him and the well assured fellowship that attended truly upon him." e

Yet, though Warwick had committed almost all his reserve to the struggle on Exeter's wing, his hopes were high. When Oxford returned from the pursuit of Hastings' broken force, he would fall upon Edward's rear; and Exeter had sent word that he was thrusting Richard's men towards the fatal trap of the hollow. Edward, in his turn, sensed that victory depended upon his reserve, which he had grimly husbanded even after the collapse of his left. If his brother Richard could hold out . . . Messengers came and went through the mist. The answer was always the same: Richard would hold, without reinforcements. Suddenly the King glimpsed a confused movement in Montagu's right center. Horsemen appeared, recoiled. Men were shouting, "Treason! Treason!" . . .

It had taken the Earl of Oxford some time to rally his men, happily looting in Barnet, and to reform their ranks. Hastening up the road to strike Edward's rear, he collided with Montagu's flank instead; the fog had hidden from him the fact that the line of battle had swung round. In the poor visibility, Montagu's men mistook Oxford's banner of a star with streams for King Edward's emblem of a blazing sun. Thinking they .were being attacked on the flank by the enemy, they promptly delivered a stiff volley of arrows. Oxford's force was thrown back in confusion. Somebody cried, "Treason!" The cry was taken up by both parties. Panic spread to Montagu's troops. The smoldering resentment between Neville followers and old Lancastrians had done its work. Thinking that they had been betrayed, Oxford and his men