Revolutionary Petunias (4 page)

Read Revolutionary Petunias Online

Authors: Alice Walker

In the late sixties through the seventies, Walker produced several books, including her first novel,

The Third Life of Grange Copeland

(1970), and her first story collection,

In Love & Trouble

(1973). During this time she also pursued a number of other ambitions, such as working as an editor for

Ms.

magazine, assisting anti-poverty campaigns, and helping to bring canonical novelist Zora Neale Hurston back into the public eye.

With the 1982 release of her third novel,

The Color Purple

, Walker earned a reputation as one of America’s premier authors. The book would go on to sell fifteen million copies and be adapted into an Academy Award–nominated film by director Steven Spielberg. After the publication of

The Color Purple

, Walker had a tremendously prolific decade. She produced a number of acclaimed novels, including

You Can’t Keep a Good Woman Down

(1982),

The Temple of My Familiar

(1989), and

Possessing the Secret of Joy

(1992), as well as the poetry collections

Horses Make a Landscape Look More Beautiful

(1985) and

Her Blue Body Everything We Know

(1991). During this time Walker also began to distinguish herself as an essayist and nonfiction writer with collections on race, feminism, and culture, including

In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens

(1983) and

Living by the Word

(1988). Another collection of poetry,

Hard Times Require Furious Dancing

, was released in 2010, followed by her memoir,

The Chicken Chronicles

, in the spring of 2011.

Currently, Walker lives in Northern California, and spends much of her time traveling, teaching, and working for human rights and civil liberties in the United States and abroad. She continues to write and publish along with her many other activities.

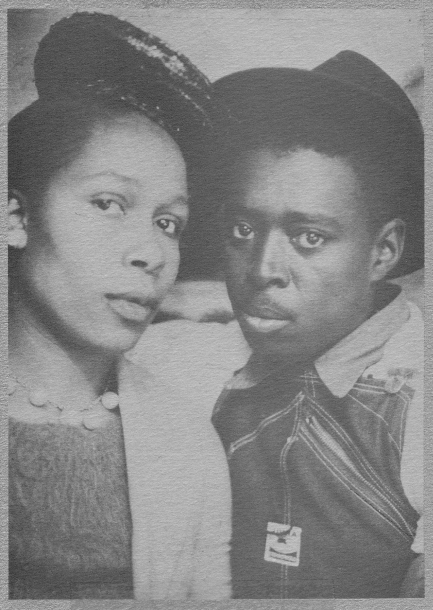

Alice’s parents, Minnie Tallulah Grant and Willie Lee Walker, in the 1930s. Willie Lee was brave and hardworking, and Minnie Lou was strong, thoughtful, and kind—and just as hardworking as her husband. Alice remembers her mother as a strong-willed woman who never allowed herself or her children to be cowed by anyone. Alice cherished both of her parents “for all they were able to do to bring up eight children, under incredibly harsh conditions, to instill in us a sense of the importance of education, for instance, the love of beauty, the respect for hard work, and the freedom to be whoever you are.”

Harlem Renaissance writer Zora Neale Hurston during her days in New York City. Hurston, who fell into obscurity after her death, had a profound influence on Walker. Indeed, Walker’s 1975 essay, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” played a crucial role in resurrecting Hurston’s reputation as a major figure in American literature. Walker paid further tribute to her “literary aunt” when she purchased a headstone for Hurston’s grave, which had gone unmarked for over a decade. The inscription on the tombstone reads, “A Genius of the South.”

Alice (front) in Kenya in 1965. She traveled there to help build the school pictured in the background as part of the Experiment in International Living Program. It was here that Walker first witnessed the practice of female genital mutilation, a practice that she has since worked to eradicate.

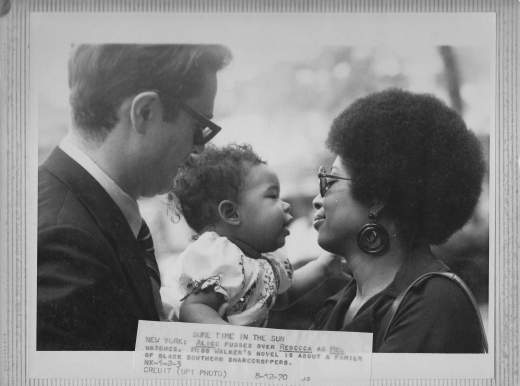

Walker with her former husband, Melvyn Leventhal, a Brooklyn native. The couple met in Mississippi and bonded over their mutual involvement in the struggle for civil rights—he as a budding litigator for the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, she as one of the organization’s workers responsible for taking depositions from disenfranchised black voters. Despite disapproval from their respective families, Alice and Melvyn wed in New York City in 1967. They then returned to Mississippi, where they were often subjected to threats from the Ku Klux Klan. Eventually the pressures of living in the violent, segregated state, coupled with their divergent career paths, caused the pair to drift apart. They divorced amicably in 1976.

Alice and Melvyn with their daughter, Rebecca, who would also grow up to become a writer, in 1970. Alice had just published her debut novel,

The Third Life of Grange Copeland

, which garnered significant praise and prompted these perceptive words from critic Kay Bourne: “Most poignant is the relating of the lives of black women, who were ready and strong and trusted, only to so often be abused by the conditions of their oppressed lives and the misdirected anger of their men.” Alice characterized it as “an incredibly difficult novel to write,” since it forced her to confront the violence African Americans inflicted on each other in the face of white oppression.

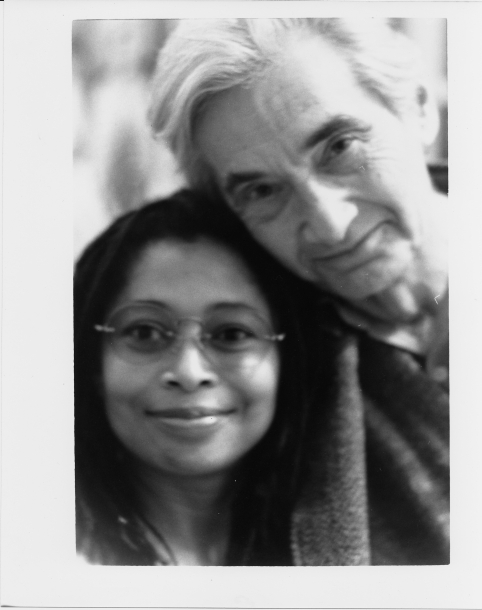

Alice and her partner of thirteen years, Robert L. Allen, a noted scholar of American history, pose for a portrait. The picture was taken at a celebration the couple hosted after the publication of

I Love Myself When I Am Laughing

, an anthology of Zora Neale Hurston’s writings that Alice edited.

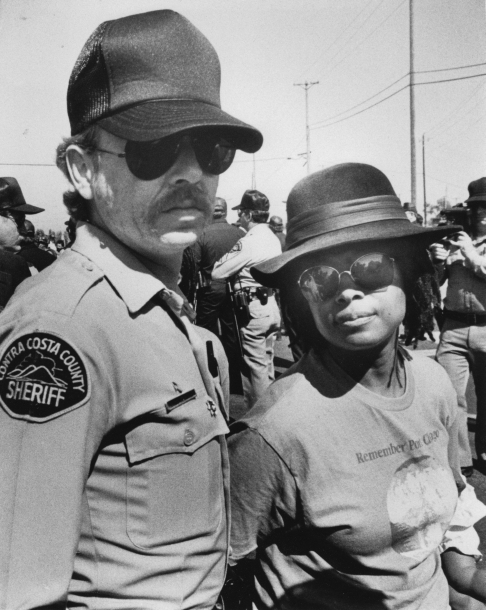

Walker being taken into custody at a 1980s demonstration against weapons shipments sent from Concord, California, to Central and South America. Her shirt reads: “Remember Port Chicago.” This is a reference to an explosion that killed hundreds of sailors stationed in Concord during World War II—most of them black—while they were loading munitions onto a cargo vessel. Walker has remained a dedicated political activist since the 1960s, when she returned to the South after graduating from Sarah Lawrence to help register black voters. Recently, she was arrested with fellow California-based author Maxine Hong Kingston in Washington, DC, during a protest against the U.S. invasion of Iraq. “My activism—cultural, political, spiritual—is rooted in my love of nature and my delight in human beings,” Walker explains.

Walker with celebrated historian Howard Zinn, who taught one of her classes at Spelman College, in the 1960s. Walker developed a lifelong friendship with Zinn and considered him one of her mentors. The two shared a passion for political activism and a desire to shed light on the conditions of the oppressed. “I was Howard’s student for only a semester,” she says, “but in fact, I have learned from him all my life. His way with resistance—steady, persistent, impersonal, often with humor—is a teaching I cherish.”