Read Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made Online

Authors: Andy Hertzfeld

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General, #Industries, #Computers & Information Technology, #Workplace Culture, #Research & Development, #Computers, #Operating Systems, #Macintosh, #Hardware

Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made (4 page)

I told Dick that I agreed that Apple had made some poor hires over the last year, especially some of the managers, but a Stalin-like purge was not a valid way to run a company. I complained about Rick's firing and told him that the situation made me feel alienated from the company. I was the type of programmer who had to believe in what I was doing, and I wasn't so sure about Apple's values anymore.

When I came in to work the next morning, there was a message on my desk from Mike Scott's secretary, saying that he wanted to talk to me; obviously Dick must have talked to him. I called her back and arranged to show up at his office in an hour. Scotty looked harried, and our conversation was interrupted a few times by various phone calls. Scotty told me that he had heard that I was upset, and thinking about leaving, and wanted me to know that he wanted me to stay. He asked me what he could do to get me excited about Apple again. I told him that I might like to work on the Macintosh, with Burrell and Bud.

Later that afternoon, Scotty's secretary called to tell me that she arranged for me to talk with Steve Jobs. Steve had been involved with the Mac project for more than a month now, and, although I didn't know it at the time, had dismissed the founder of the project, Jef Raskin, the day before, making him take a mandatory leave of absence after Jef had complained about Steve's leadership.

Lots of people at Apple were afraid of Steve Jobs, because of his spontaneous temper tantrums and his proclivity to tell everyone exactly what he thought, which often wasn't very favorable. But he was always nice to me, although sometimes a bit dismissive, in the few interactions that I had with him. I was excited to be talking with him about working on the Mac.

The first thing he said to me when I walked into his office was "Are you any good? We only want really good people working on the Mac, and I'm not sure you're good enough." I told him that yes, I thought that I was pretty good. I was friends with Burrell, and had already helped him out with software a few times.

"I hear that you're creative", Steve continued. "Are you really creative?"

I told him that I wasn't the best judge of that, but that I'd love to work on the Mac, and thought that I'd do a great job. He said he'd get back to me soon about it.

A couple of hours later, around 4:30pm, I was back to work on DOS 4.0 for the Apple II. I was working on low-level code for the system, interrupt handlers and dispatchers, when all of a sudden I notice Steve Jobs peering over the wall of my cubicle.

"I've got good news for you", he told me. "You're working on the Mac team now. Come with me and I'll take you over to your new desk."

"Hey, that's great", I responded. "I just need a day or two to finish up what I'm doing here, and I can start on the Mac on Monday."

"What are you working on? What's more important than working on the Macintosh?"

"Well, I've just started a new OS for the Apple II, DOS 4.0, and I want to get things in good enough shape so someone else could take it over."

"No, you're just wasting your time with that! Who cares about the Apple II? The Apple II will be dead in a few years. Your OS will be obsolete before it's finished. The Macintosh is the future of Apple, and you're going to start on it now!".

With that, he walked over to my desk, found the power cord to my Apple II, and gave it a sharp tug, pulling it out of the socket, causing my machine to lose power and the code I was working on to vanish. He unplugged my monitor and put it on top of the computer, and then picked both of them up and started walking away. "Come with me. I'm going to take you to your new desk."

We walked outside to Steve's silver Mercedes and he dropped my computer into the trunk. We drove a few blocks to the corner of Stevens Creek and Saratoga-Sunnyvale, to a non-descript, brown-shingled, two story office building next to a Texaco station, while Steve waxed eloquent about how great the Macintosh was going to be. We walked up to the second floor, and into an unlocked door. Steve plopped my system down on a desk in an office near the back of the building and said, "Here's your new desk. Welcome to the Mac team!", before darting off.

I started looking around the office, and saw Burrell Smith and Brian Howard in the next room, huddled over a logic analyzer connected to a prototype board. I told them what happened and they said Steve had been over earlier, asking them if they thought I was any good. They were happy that I joined the team.

After helping them a bit with the disk diagnostic routines they were trying to debug, I returned to my new desk and looked inside the drawers. I was surprised to see that it was still full of someone else's stuff. In fact, the bottom drawer had all kinds of unusual stuff, including various kinds of model airplanes, and some photography equipment. I later found out that Steve had assigned me to Jef Raskin's old desk, which he hadn't had time to move out of yet.

More Like A Porsche

by Andy Hertzfeld in March 1981

The original Macintosh industrial design

In March 1981, I had been working on the Mac team for only a month. I was used to coming back to the office after dinner and working for a few hours in the evening. Even though many of the early Mac team members usually worked late, and we often went out to dinner together, I was by myself one evening when I returned to Texaco Towers after dinner around 8pm. As soon as I entered the building, I heard loud voices emanating from Bud's office, which was adjacent to mine, apparently engaged in a spirited discussion.

"It's got to be different, different from everything else." I recognized Steve Jobs' voice before I saw him as I passed by the door of Bud's office. He was standing near the doorway, near our only working prototype, conversing with someone who I didn't recognize, that Steve introduced to me as James Ferris, Apple's director of Creative Services. "James is helping me figure out what the Mac should look like," he told me.

The plan of record for the Macintosh industrial design was still the one conceived by Jef Raskin, which chose a horizontally oriented, lunch-box type shape, with the keyboard folding up into the lid of the computer for easy transportability, kind of like the Osborne I, which we weren't aware of at the time. But Steve had a real passion for industrial design, and he never seriously considered following Jef's recommendations.

I went into my office and started to program, working on improving the code that drove the serial link between the Mac and Lisa, at Bud's request. But I couldn't help but overhear the passionate discussion taking place next door between Steve and James Ferris. For some reason, they were talking about cars.

"We need it to have a classic look, that won't go out of style, like the Volkswagen Beetle", I heard Steve tell James.

"No, that's not right.", James replied. "The lines should be voluptuous, like a Ferrari."

"Not a Ferrari, that's not right either", Steve responded, apparently excited by the car comparison. "It should be more like a Porsche!" Not so coincidentally, in those days Steve was driving a Porsche 928.

I thought it was kind of pompous to compare computers with sports cars, even metaphorically. But I was impressed with Steve's passion for elegance in the industrial design and his powers of discrimination continually amazed me as the design took shape.

Steve recruited Jerry Manock to lead the industrial design effort. Jerry was the early Apple employee who had designed the breakthrough plastic case for the Apple II, initially as a contractor before signing up as an employee. For the Macintosh, Jerry recruited a talented designer named Terry Oyama, to do most of the detailed drafting of the actual design. The hard tooling for the plastic case was the component with the longest lead time, so we had to get started right away.

A week or so after the car conversation, Steve and Jerry decided that the Macintosh should defy convention and have a vertical orientation, with the display above the disk drive instead of next to it, in order to minimize desktop footprint, which also dictated a detachable keyboard. That was enough of a direction for Terry to draft a preliminary design and fabricate a painted, plaster model.

We all gathered around for the unveiling of the first model. Steve asked each one of us, in turn, to say what we thought about it. I though it was cute and attractive, looking a lot like an Apple II, but with a distinctive personality all its own. But, after everyone else had their say, Steve cut loose with a torrent of merciless criticism.

"It's way too boxy, it's got to be more curvaceous. The radius of the first chamfer needs to be bigger, and I don't like the size of the bezel. But it's a start."

I didn't even know what a chamfer was, but Steve was evidently fluent in the language of industrial design, and extremely demanding about it. Over the next few months, Jerry and Terry iterated on the design. Every month or so, there was a new plaster model. Before a new one was unveiled to the team, Jerry lined up all of the previous ones, so we could compare the new one with past efforts. One notable improvement was the addition of a handle at the top of the case, to make it easier to carry. By the fourth model, I could barely distinguish it from the third one, but Steve was always critical and decisive, saying he loved or hated a detail that I could barely perceive.

At one point, when we were almost finished, Steve called up Jerry over the weekend and told him that we had to change everything. He had seen an elegant new Cuisinart at Macys' on Saturday, and he decided that the Mac should look more like that. So Terry did a whole new design, based around the Cuisinart concept, but it didn't pan out, and soon we were back on the old track, after a one-week diversion.

After five or six models, Steve signed off on the design, and the industrial design team shifted gears to do the laborious engineering work necessary to convert the conceptual model into a real, manufacturable plastic case. In February 1982, it was finally time to release the design for tooling. We held a little party, complete with champagne (see

signing party

) to celebrate sending off the design into the world, the first major component of the Macintosh to be completed.

He's Only in Field Service

by steve blank in March 1981

In the early eighties, I was at Zilog as the (very junior) product marketing manager for the Z8000 peripheral chips which included the new SCC chip, short for "Serial Communications Controller". I remember getting a call from our local salesman that someone at Apple wanted more technical information than just the spec sheets about our new (not yet shipping) chip. I vividly remember the sales guy saying, "its only some kid in field service, I'm too busy, why don't you drive over there and talk to him."

Zilog was also in Cupertino, near Apple on Bubb drive, and I remember driving to a small non-descript Apple building at the intersection of Stevens Creek and Sunnyvale/Saratoga (most of Apple's buildings at that time were on Bandley Drive.) I had a pleasant meeting and was as convincing as a marketing type could be to a very earnest engineer, mostly promising the moon for a versatile but then very buggy piece of silicon. I remember him thanking me for coming, saying we were the only chip company who cared enough to call on him (little did he know.)

I thought nothing about the meeting until years later. Long gone from Zilog I saw the picture of the Mac team. The field service guy I had pitched the chip to was Burrell Smith. The SCC had been designed into the Mac, and some sales guy who was too busy to take the meeting was probably retired in Maui on the commissions.

Early Demos

by Andy Hertzfeld in April 1981

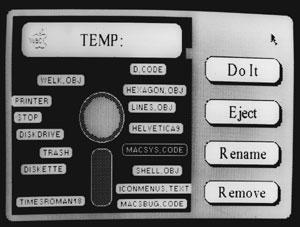

Early Finder Prototype from Feb 1982

The first demo program for the 68000-based Macintosh was written by Bud Tribble, as part of the original boot ROM. It filled the screen with the word 'hello' in tiny letters, more than a hundred times. When the Mac was switched on, it performed some hardware diagnostics, filled the screen with 'hello', and then listened to its serial ports for commands to execute. The 'hellos' told us that everything was working OK.