Revolution

Authors: Russell Brand

This book is a work of nonfiction based on the life, experiences, and recollections of the author. In some limited cases, names of people or places, dates, sequences, or the detail of events have been changed.

Copyright © 2014 by Russell Brand

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

B

ALLANTINE

and the H

OUSE

colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Published simultaneously in the United Kingdom by Century, a division of The Random House Group, London. This edition published by arrangement with Century, a division of The Random House Group.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Apostrophe S Productions, Inc.:

Excerpt from

Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth with Bill Moyers

. Used by permission of Apostrophe S Productions, Inc.

Noam Chomsky:

Tomgram: Noam Chomsky, America’s Real Foreign Policy

by Noam Chomsky. Reprinted by permission of Noam Chomsky.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt:

Excerpt from

Homage to Catalonia

by George Orwell, copyright © 1952 and renewed 1980 by Sonia Brownell Orwell. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

L

IBRARY OF

C

ONGRESS

C

ATALOGING-IN

-P

UBLICATION

D

ATA

Brand, Russell

Revolution / Russell Brand.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-101-88291-7

ebook ISBN 978-1-101-88292-4

1. Social movements. 2. Social action. 3. Social change. 4. Political participation. 5. Income distribution. 6. Brand, Russell, 1975—Political and social views. I. Title.

HM881.B73 2014

303.48′4—dc23 2014031985

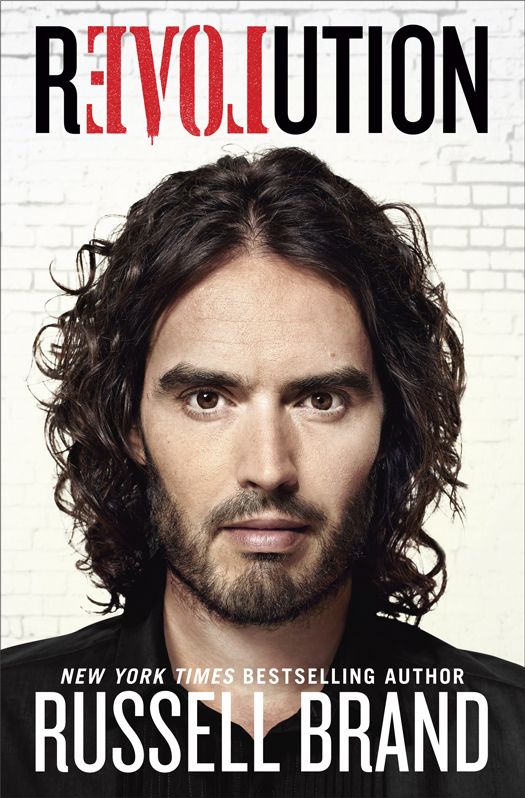

Jacket design: One Darnley Road

Jacket photograph: Dean Chalkley

Jacket lettering: Shepard Fairey

v3.1

You Say You Want A Revolution

J

EREMY

P

AXMAN IS

B

RITAIN

’

S FOREMOST POLITICAL INTERVIEWER

. He is fierce, not in a pugnacious way, like a salivating pit-bull; no, like a somnolent croc, eyes above the surface, knowing you will make a false move, waiting. Then snap, thrash, roll, you’re finished. He eats home secretaries for breakfast, shits chancellors, and wipes his arse on prime ministers. In five minutes’ time I will be interviewed by Jeremy, on our nation’s foremost news analysis show,

Newsnight

.

That’s why I’m on my knees now, in the toilet of the lobby of the Landmark Hotel. Praying. “God, please make me a channel of your peace.” The first line of the St. Francis prayer, popularized by Mother Teresa, bastardized by Margaret Thatcher, and cherished by those of us who have fallen through the cracks and floated ourselves back up with crack.

I just want to be a channel of the peace. The peace exists; I don’t need, thank God, to create the peace. All I have to do is become open and the peace will come, the peace is already there. Mother Teresa, one could argue, is a testimony to the principles outlined in this prayer; through service she conquered the lower, selfish drives that serve survival and the ego, and become a tool of a Higher Purpose, or God. Margaret Thatcher’s case is less clear. What God she was serving in her systematic destruction of the values of our country as she jived in the brilliantined shadow of Ronnie Reagan is a mystery. But as she stands, newly elected and spattered by fore-boding rain outside Number 10, it is the St. Francis prayer that Maggie recites:

Lord, make me a channel of thy peace;

That where there is hatred, I may bring love;

That where there is wrong, I may bring the spirit of forgiveness;

That where there is discord, I may bring harmony;

That where there is error, I may bring truth;

That where there is doubt, I may bring faith;

That where there is despair, I may bring hope;

That where there are shadows, I may bring light;

That where there is sadness, I may bring joy

.

Lord, grant that I may seek rather to comfort than to be comforted;

To understand, than to be understood;

To love, than to be loved

.

For it is by self-forgetting that one finds

.

It is by forgiving that one is forgiven

.

It is by dying that one awakens to eternal life

.

Amen

.

Now, I don’t think she belted out the whole thing there and then, but you don’t need to be Jeremy Paxman to see that Margaret Thatcher somewhat strayed from the sentiments outlined in this prayer.

She didn’t bring much love to the miners of northern England. She wasn’t that forgiving to the Argentinian sailors on the

Belgrano

. There was very little harmony among the poll-tax rioters and the police. You get the idea. So I suppose the prayer is not infallible; in the wrong hands it can evidently become a mantra for self-centered nihilism.

That isn’t the prayer’s fault, though. For me it is a code that attunes my mind to its natural state: union, connection, oneness. In the Creole ramblings that I offer up in the frantic lavatorial incantations that precede the interview—some Vedic chants, yogic murmurs, and even some Eminem lyrics—what I am trying to do is to connect, transcend, get out of myself. That is what I’ve been trying to do my whole life—get out of myself, get out of my mind, get out of Grays, get out of the feeling that I’m not good enough, that I’m alone, that I’m never going to be happy or loved, and I’ve tried to do it in a multitude of ways, always with the same outcome.

I’ve greeted a cavalcade of gleaming false idols like a jam-jar native, prostrate before the great white master. As a little boy, chocolate and television were deities to me; I sat on my knees before that goggle-box in spellbound devotion, the Penguin sacrament ritualistically devoured (nibble chocolate coating first, scrape center with teeth, then eat biscuit). As a teen with porn, I was locked up mute like a Trappist in that bathroom, flagellating with stifled wails. With drugs and alcohol, I made the pilgrimage to any bridge or corner and made my donations in the penury my God demanded. Then came fame, where I studied like Augustine and voyaged like a Jesuit. I was a zealous devotee to every prophet of the panoply, and none brought anything but pain and disillusion. Only when salvation was offered did I become circumspect; only when the solution became available did I examine with a skeptical eye.

When I necked five-quid bottles of vodka, I did not read the label. When I scored rocks and bags off tumbleweed hobos blowing through the no-man’s-land of Hackney estates, I conducted no litmus tests. As I sought sanctuary in twilight cemeteries entombed in strangers’ limbs, I barely even asked their names.

But, when the true dawn came, when the light rose, when I felt the fusion, I had no faith; I had questions. How do I know this is real? What if it doesn’t work? How can I, after everything, just trust and let go? I still have questions, and in the inquisitor’s chair in the suite-cum-studio of the Landmark hotel, so does Jeremy Paxman.

“So …” he says, in a voice so intoned with sarcasm I wonder whether it will come out of his nose, “how, if you think people shouldn’t vote, are we going to change the world?”

“Through Revolution,” I say.

“You want a Revolution?”

“Yeah.”

“You believe there’s going to be a Revolution?” He shunts the question at me like a billiard ball.

“Jeremy, I have no doubt,” I reply.

Jeremy has been round the block a few times and has sat across from every johnny-come-lately mug with a cause and a plug who has had the gall to crop up on his show in the last twenty years. He looks me up and down—the hair, the beard, the ridiculous scarf.

“And how, may I ask, is this Revolution going to come about?”

Now, that is a very good question; it’s a question that a far less skilled interviewer than Jeremy Paxman would lob at you. But this isn’t a far less skilled one—it’s Paxman. And not just Paxman; it’s my headmaster, it’s the arresting officer, it’s the people at work, friends, relatives, well-wishers, and bystanders. “How will this Revolution work? How can we change the world? How can we change ourselves? Can we really overthrow the corrupt and the powerful, not just the corruption in society but in ourselves?”

Well, I know the answer’s yes. And as for the more complicated aspects of that question, well, I may not be Margaret Thatcher and I’m certainly no Mother Teresa (except we agree on condoms), but I’ve given it some thought, so, here we go, sit down and strap in.

Heroes’ Journey

T

HE FIRST BETRAYAL IS IN THE NAME

. “L

AKESIDE

,”

THE GIANT

shopping center, a mall to Americans, and “maul” is right, because these citadels of global brands are not tender lovers, it is not a consensual caress, it’s a maul.

After a slow, seductive drum roll of propaganda beaten out in already yellowing local rags, Lakeside shopping center landed in the defunct chalk pits of Grays, where I grew up, like a UFO.

A magnificent cathedral of glass and steel, adjacent, as the name suggests, to a lake. There was as yet no lake. The lake was, of course, man-made. The name Lakeside, a humdrum tick-tock hymn to mundanity and nature, required the manufacture of the lake its name implied, just to make sense of itself.