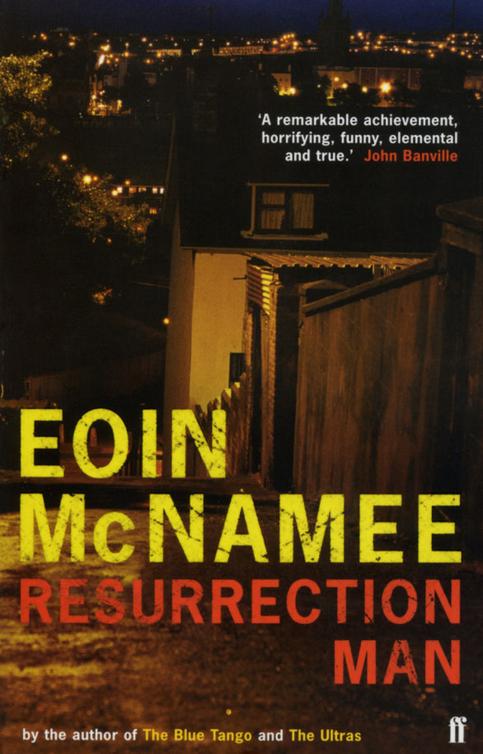

Resurrection Man

Authors: Eoin McNamee

Further praise for

Resurrection

Man

:

‘McNamee shows all the promise of an Irish Cormac McCarthy … This horrible, brilliant book allows us both to condemn and also to understand the awful addictive excitement of violence, the bloody poetry of it.’

Arena

‘

Resurrection

Man

is a voyage through the diseased arteries of a city. Perpetually close to the bone and imbued with a luminous mundane evil, it lays out the anatomy of a terror in stark and exquisite prose.’ Dermot Bolger

‘A highly readable debut, black and still, creating a pace of its own amidst a bloody conflict.’

List

‘The poetic cadence and unusual phrasing are skilfully deployed to create a bleakly lyrical, vivid and horrible enthralling

dream-scape

… spellbinding.’

Irish

Times

Afterwards Dorcas would admit without shame that having moved house so often was a disturbance to Victor’s childhood. But a suspicion would arise in each place that they were Catholics masquerading as Protestants. Her husband James was no help in this regard. He was so backward and shy he needed to stand up twice before he cast a shadow. Dorcas would maintain that Victor did not learn bigotry at her knee even though she herself had little tolerance of the Roman persuasion. She believed that all he really wanted to be was a mature and responsible member of society, loyal to the crown and devoted to his mother. But he suffered from

incomprehension

. He was in pain because of life.

*

Dorcas and James came from Sailortown in the dock area. Sailortown disappeared gradually after the war. There is a dual carriageway running through the area now. There isn’t even a place where you can stand to watch the traffic. You’d have to get up on a warehouse roof where you might find a lone sniper at dawn, feeling rigorous in the cold and thinking about migration as he watches the traffic, a movement along chosen routes.

The city itself has withdrawn into its placenames.

Palestine

Street. Balaklava Street. The names of captured ports, lost battles, forgotten outposts held against inner darkness. There is a sense of collapsed trade and accumulate decline.

In its names alone the city holds commerce with itself, a furtive levying of tariffs in the shadow.

*

James was a dock labourer. He had this deadpan look, a listener to distant jokes. It was like he saw himself as some hardluck figure for whom silence was a condition of survival. Bearing the name of Kelly meant that he was always suspected of being a Catholic. He protected himself by effacement. He was a quiet accomplice to the years of his fatherhood and left no detectable trace.

Sometimes if Dorcas insisted he would take his own son to Linfield matches at Windsor Park. He would get excited and shout at the team. Come on the blues. Victor would look at him then but he would have put the shout away like it was something he’d sneaked on to the terraces under his coat and was afraid to use again.

Once he took Victor up to the projection room during the matinee at the Apollo cinema on the Shankill Road. The projectionist was Chalky White who had been to school with James. Chalky was six feet tall, stooped, with carbon residue from the lamps in his hair and his moustache. There were two big Peerless projectors with asbestos chimneys leading into the ceiling. There were aluminium film canisters on the floor and long Bakelite fuseboxes on the wall. The air smelt of phosphorous, chemical fire.

Chalky showed Victor a long white scar on his arm where he had accidentally touched the hot casing.

‘Laid it open to the bone,’ Chalky said. He showed Victor the slit in the wall where the projectionist could watch the picture. He talked about film stars he admired. Marion Nixon, Olive Brook. Victor liked Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney in

Public

Enemy.

When he looked through the slit he could see Laurence Tierney as John Dillinger laid out on a morgue slab like a specimen of extinction. Flash bulbs went off. A woman said I thought he’d be better looking. Dillinger

kept his eyes open, looking beyond the women and the reporters towards his Dakota birthplace, small farms glistening under a siege moon.

James had a photograph of his own father which he kept in his wallet. He was standing with other men in his shift at the docks. They were leaning on their shovels, smoking and stroking their long moustaches like some grim interim

government

of the dead.

Sometimes when he was watching TV Victor would think he saw his father in the crowd that collected around a scene of disaster. Or standing slightly apart at some great event. Or on the terraces watching great Linfield teams of the fifties and sixties pulling deep crosses back from the byline, scoring penalties in the rain.

*

After the Apollo Victor worked hard at getting the gangster walk right. It was a combination of lethal movements and unexpected half-looks. An awareness of G-men. During the day he would mitch school and go down to the docks. He would avoid the whores at the dock gate. Their blondie hair they got from a bottle, Dorcas said, and the hair waved in his dreams like a field of terrifying wheat.

Victor spent most of these days behind the wheel of an old Ford Zephyr on blocks at the edge of the dock. The engine had been removed and there was oily grass growing through the wheel arches. It had dangerous-looking fins on the back and chrome bumpers which Victor polished. From the front seat he could see the tarred roofs of goods wagons in the stockyard sidings. Dorcas’ brother worked there in a cattle exporter’s office. He would sit at their fire at night and talk about cattle, which Victor hated. He had a passion for his work: the bills of lading, statistics of weight loss during transit, mortality rates.

One night when he thought Victor wasn’t listening he told Dorcas about finding a Catholic girl in the shed used for storing salt. It was during the thirties. Winter. The wagons were frozen

to the rails. The air itself had forceps. The girl and the baby had died in the salt shed with the steam of her labour above her head and the cord uncut between her thighs. When they found her they sliced the cord with the blade of a shovel. When they lifted her they saw salt crystals stuck to her thighs like some geodic shift quarried for her in the moment of her death.

Victor sat at the wheel of the car until dusk most nights. He preferred it when it began to get dark. By day the city seemed ancient and ambiguous. Its power was dissipated by exposure to daylight. It looked derelict and colonial. There was a sense of curfew, produce rotting in the market-place. At night it described itself by its lights, defining streets like a code of destinations. Victor would sit with the big wheel of the Zephyr pressed against his chest and think about John Dillinger’s face seen through a windscreen at night, looking pinched by rain and the deceit of women.

It was dusk when Trevor Garrity and Alan McAtee from school found Victor in the car. Garrity sprang the bootlid and looked inside. McAtee went to the driver’s window and looked in. Victor had a sense of frontiers, a passport opened to the raw, betrayed face of your younger self.

‘How’s Pat?’ McAtee said. He was three years older and had bad teeth which Victor couldn’t stand.

‘My name’s Victor. Pat’s a Taig name.’ He wondered how Edward G. Robinson would handle this. Later he would realize that men had been doing this for centuries, stopping each other in remote places, demanding the credentials of race and nationality.

‘Kelly sounds like a Taig name to me,’ McAtee said casually. ‘Your ma must of rid a Taig.’

‘Come here till you see this,’ Garrity said. McAtee went to the back of the car. Victor followed him. He kept most of his private possessions in the boot and Garrity had emptied them all out onto the ground. There was a scout knife with a fake wooden handle. Twenty Gallagher’s blues with a box of matches from the Rotterdam bar. A Smirnoff bottle opener. A

copy of

Intimate

Secrets

Incorporating

Married

Woman

that Victor had found. When he heard Garrity at the boot Victor expected to lose something. The cigarettes. The knife. Instead he saw that Garrity had the magazine.

‘Come here till you see this,’ Garrity repeated. McAtee stood beside him and began to read over his shoulder.

‘Fuck me, my hubby couldn’t believe …’

‘His wicked love potion drove me …’

‘I felt a shudder through my most private zone …’

‘My secret Taig lover by Mrs Dorcas Kelly.’

Victor reached for the knife on the ground. McAtee put his foot on it.

‘Pat didn’t like that.’

‘Pat’s sensitive about his ma.’

Victor waited. He could see the shapes of violence laid out in his head like a police diagram with skid marks leading away.

He learned that there was a pattern to such moments. A framework of inconsequential detail. When he took the first blow on the side of the head and went down he was thinking about the last moments of gangsters. He had a sudden awareness of texture and temperature. He understood about people talking about the weather at funerals. He imagined being a gangster and seeing a cockroach or a metal fire escape or something else they had in America. Garrity kicked him in the crotch. A shudder most private. The magazine lay open on the ground beside his head. The Wife of the Month had long yellow breasts, half-hidden, which she seemed to offer in consolation. Her mouth was open as if she was about to utter mysteries, messages of explicit loneliness directed at him. Must of rid a Taig.

*

They moved to so many districts it didn’t seem to matter what Dorcas thought. To rear a son in such a selection of streets did not donate stability to his life; however, she did her best. Victor always took up with older boys, men sometimes, who

were not concerned about his moral welfare. He was always in trouble, and she possessed no means to stop it. She thought it was a wonder how she managed to survive this life at all. Pregnant at age seventeen and having to marry in such haste she could barely walk up the aisle with dignity. She thought sometimes she might have married a shadow or a ghost, James was so quiet. She did her duty by him, although there were times she felt an awful emptiness of regret. It was necessary to have firm beliefs to get by. She remembered that Victor wrote to her often of his childhood when he was in prison, always starting his letters ‘dear mother’ and ending ‘yr loving son’.

By age twelve Victor was in trouble for larceny and

shop-breaking,

led down that path by his elders. She talked to the magistrate with spirit and he got the benefit of the Probation Act that time. James his father never came near the court. She accepted nothing from Victor that was not got honest, and he was always there with small gifts, which is why she wondered at the newspapers – sometimes they printed such lies.

*

Victor later befriended Garrity and McAtee. He showed them how you could take bus passes off younger pupils and sell them on. Victor would stop someone at the school gate. McAtee would hold them and Garrity would beat them. Victor watched the eyes. It was a question of waiting for a certain expression. You directed a victim towards gratitude. You expected him to acknowledge the lesson in power.

People learned to be obsequious, to defer to him. This led to problems of isolation. He believed he knew how Elvis felt.

After school he would walk down to University Street where he would wait for the Methody girls to come out wearing the compulsory black stockings and high-heeled shoes. They took lessons in deportment, sexual gravitas. Their skirts were worn an inch above the knee and stocking seams were checked with a steel ruler for straightness. They took make-up classes

where they learned how to obscure vital faults and arouse precise longings. They were deeply aware of their own

attractions

. They knew how to prolong moments of anticipation. Lace brassières were visible.

Their fathers would gather in University Street to drive them to their homes outside the city. They performed this task unsmilingly. They avoided looking at the legs of their

daughters

’ classmates and greeted each other with stern nods only. They possessed their daughters as if they were branches of obscure knowledge. There were things that were penetrable only to fathers of beautiful girls, exclusive sorrows.

Afterwards he would go down to the Cornmarket to listen to the preachers and their recital of sectarian histories. They were thin men dressed in black with ravaged faces. They predicted famine and spoke in tongues. Their eyes seemed displaced in time. They would eat sparsely, sleep on boards, dream in monochrome. There was a network of small

congregations

and merciless theologies throughout the city.

Congregations

of the wrathful. Baptist. Free Presbyterian, Lutheran, Wesleyan, Church of Latter-day Saints, Seventh Day

Adventists

, Quakerism, Covenanters, Salvationists, Buchmanites. Pentecostalists. Tin gospel halls on the edges of the shipyard were booked by visiting preachers for months in advance. Bible texts were carefully painted on gable walls.

Victor listened to their talk of Catholics. The whore of Rome. There were barbarous rites, martyrs racked in pain. The Pope’s cells were plastered with the gore of delicate Protestant women. Catholics were plotters, heretics, casual betrayers.

When he went home he would find his father washing in the kitchen and Dorcas watching television.

This

Is

Your

Life.

Dorcas would ask where he had been.

‘Down at the Cornmarket.’

‘Them preachers. In America they have them preachers on the television.’ His father walked in, drying his neck.

‘You’d better mind yourself, Victor. End up saved, so you will,’ he said.

Victor and Dorcas turned to look at each other. James stared over their heads at the television, his inattention cancelling the spoken word.

‘Did you hear something?’ Dorcas asked Victor.

‘Never heard a thing, ma.’

James opened the back door and went out. He kept pigeons at the back. Dorcas said he spent more time with the pigeons than he did with his own family. He never even spent time watching television with them, but moved from one region of silence to another.

‘Your da has me tortured,’ she said.

‘Never mind, ma,’ Victor said. ‘That guy ain’t going to do nothing to you, dollface.’ Dorcas laughed.

‘Me and yous going to fill that guy full of lead, blow this town.’

Dorcas loved it when Victor talked like this big gangster from the films, but there were times when she would discipline him with a stick in the yard. She remembered that she would be beating Victor and James would cross the yard as if they were not there. Sometimes she thought that what her husband had was a kind of madness. Later Victor read books on it in the Crumlin Road prison, and told her about the different forms of mental absence.