Resolute (14 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

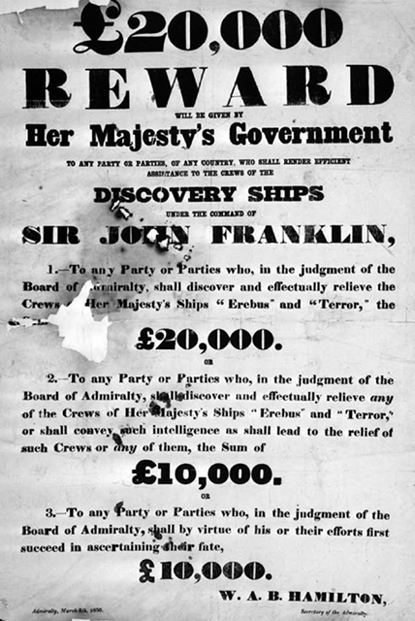

THIS REWARD POSTER

revealed both the Admiralty's and the Arctic Council's growing concern about Franklin's disappearance. Eventually the £10,000 reward for ascertaining the expedition's fate would engender bitter controversy.

At the same time that Richardson searched for Franklin by land, two ships would be sent out to trace the route that Franklin had been instructed to follow. This meant sailing through Lancaster Sound and Barrow Strait to Melville Island and Banks Land before turning south. Command of this search was given to James Clark Ross, who had been one of John Barrow's prime choices to lead the expedition that was now the object of the search. With all of England clamoring for news of Franklin's whereabouts, Ross's wife had released him from his promise of never returning to the Arctic.

Finally, a third rescue party was to be sent out, two ships commanded by Lieutenant W. J. S. Pullen and Captain Henry Kellett. Their orders were to proceed directly to the Bering Strait in the hope that Franklin had made it that far. Their main objective was to serve as supply depots for both Richardson's and Ross's expeditions.

THE RICHARDSON RESCUE PARTY

, made up of five English seamen and fifteen British soldiers, left for the Arctic in late March 1848. After having screened hundreds of requests from men who wished to be named second-in-command, Richardson felt blessed to have secured the services of Dr. John Rae, a skilled surgeon and a man whose inquisitiveness about nature rivaled Richardson's. Lean, bewhiskered, and seemingly inexhaustible, Rae had been described by one of his contemporaries as “muscular and active and full of animal spirit.” At thirty-four, he was already a veteran of fourteen years in the Arctic where, in the employ of the Hudson's Bay Company, he had become something of a legend within the fur-trading company. (At the time company's governor was George Simpson, a key player in the search for the passage and Franklin, see note, page 265.) In 1846, while engaged in a survey of Melville Island, he had found himself beset by winter. With no ship in which to gain shelter, Rae and his party had become the first Europeans ever to winter on the Arctic coast, and the first to survive without any provisions except what he and his Inuit guide were able to provide by hunting caribou, musk oxen, and birds, and by fishing.

The following summer the Rae legend continued to grow as, in the process of charting 625 miles of hitherto unexplored Arctic coastline, he snowshoed 1,200 miles, living entirely off the land. Regarded by the Inuit as the most skilled snowshoe walker of his time (George Back might have argued the point), Rae prided himself on the name the natives had given himâ

Alooka

(“he who takes long strides”).

It was Rae's relationship with the Inuit that would ultimately best define him. His participation in the Richardson party would be but a prelude to his involvement in the search for John Franklin. Before it was over, Rae, more than anyone else, would have learned the natives' ways and dedicated himself to dressing like them, living like them, hunting like them, and traveling as they did. Eventually he would be the center of a controversy that would rock all of England.

But in 1848, with the Richardson party, the search for Franklin was just starting. And it was not a successful beginning. By August the expedition had reached the estuary of the MacKenzie River. It then traveled in four small boats to Wollaston Land (which, along with Victoria Land, made up a massive 84,000 square-mile island, but no one knew this at the time). After abandoning their boats, Richardson, Rae, and the others trudged overland to Fort Confidence on Great Bear Lake where they hunkered down for the winter, all without finding a single clue.

In the spring, Richardson, worn out from the journey, returned to England, leaving Rae in command. But when Rae tried to scout Wollaston Land and Victoria Land he found his way completely blocked by ice. Like Richardson, he would return home without having shed a bit of light on the Franklin mystery.

For John Rae, there would be other expeditions. But as James Clark Ross set out on

his

rescue effort he knew that this would be his last trip to the Arctic. Franklin had to be found. But there were 128 others out there as well, something Ross felt that the public sometimes tended to forget. And included among them was his closest friend, Francis Crozier, who had been given command of the

Terror.

The Admiralty sent Ross's expedition off in two large vessels, the

Enterprise

(450 tons) and the

Investigator

(400 tons). Together they carried enough supplies for a three-year search plus a full year's provisions for Franklin and his men once they were found. Aboard the vessels were two senior officers destined to become leaders in the next generation of Arctic explorers. Forty-one-year-old Robert McClure, who had been born in Wexford, Ireland, had been in the navy for twenty-four years, and had shared George Back's traumatic year aboard the

Terror

in 1836. Leopold M'Clintock had been born to Scottish parents in Dundalk, Ireland. Now twenty-nine and a seventeen-year navy veteran, he was making his first northern voyage. Neither had any idea of the momentous roles each would eventually play in the saga that was just beginning to unfold.

For whatever reasons, Ross, although one of the most experienced of the Arctic adventurers, left England later in the season than he should have, some two months after Richardson had departed. After following Franklin's path by sailing through Barrow Strait and attempting to proceed through Wellington Channel, he found his way blocked by ice. Concerned that winter was already setting in, he made his way to Port Leopold on the northeastern tip of Somerset Island in Lancaster Sound. He had no choice. He would have to spend his ninth winter in the ice.

But he would not be idle. The search for Franklin would go on even when the ships were imprisoned. After securing the vessels for the long, dark months ahead, Ross had his men begin shooting off rockets every morning and evening. If the Franklin expedition was anywhere in the area, surely they would see them. Ross also sent out members of his party to capture foxes that roamed through the vicinity where the ships lay. The animals were then fitted with metal collars upon which were punched the names of the rescue vessels, their position, and the date, “in the hopes,” as Ross would write, “that Sir John Franklin, or some of his people, might in [this] ingenious manner be appraised of assistance.”

Ross's greatest hope of finding some trace of Franklin or his whereabouts, however, was to leave his immobile ships and search as wide an area as he could by sledge. Surprisingly, he had not brought dogs with him, and the backbreaking labor of hauling the heavy, equipment-loaded sledges over the hummocks and crushed ice fell to his men.

On May 15, Ross himself took charge of the first of the sledging searches. It would be a forty-day journey that would take him first along the north side of Somerset Island and then down the island's western perimeter. His goal was to travel as far as the Magnetic Pole, the site of the discovery that had made him forever famous. But by the time he reached a point some 170 miles short of the Pole, some of his men were showing signs of snow blindness; others had sprained ankles and other injuries, and he was forced to return to the ships. By the time they got back, they had covered 539 miles.

Before making the long return journey, Ross had had his men construct a large cairn into which was placed a copper cylinder containing a lengthy note:

The cylinder which contains this paper was left here by a party detached from Her Majesty's ships

Enterprise

and

Investigator

under the command of Captain Sir James C. Ross, Royal Navy in search of the expedition of Sir John Franklin; and to inform any of his party that might find it that these ships, having wintered at Port Leopold in long. 90°W, lat. 73°52'N have formed there a depot with provisions for the use of Sir John Franklin's party sufficient for six months; also two very small depots about fifteen miles south of Cape Clarence and twelve miles south of Cape Seppings. The party are now about to return to the ships, which, as early as possible in the spring, will push forward to Melville Strait, and search the north coast of Barrow Strait; and, failing to meet the party they are seeking, will touch at Port Leopold on their way back, and then return to England before the winter shall set in.

In the months that followed, other sledging trips were launched. On one of them, a foray down the west shore of Prince Regent Inlet, Fury Beach was reached. There they found, still intact, the structure known as Somerset House where, in the winter of 1832-33, Ross, his uncle, and twenty-one others had just barely managed to survive.

By August, the sledging trips had taken a serious toll. Many of the men had become ill, some seriously. Ross himself had to take to his bed for a time. Commenting on the consequences of long-range sledging, Leopold M'Clintock would later write: “One gradually becomes more of an

animal

, under this system of constant exposure and unremitting labor.” Ironically it would be M'Clintock who, beginning with his experiences on this expedition, would become the most knowledgeable sledger of them all. It would be his expertise at coping with the difficulties of preparing the sleds properly, loading them with the proper amount of supplies, rationing the food, and providing medical care on long journeys over ice, that would enable him to facilitate the most important discoveries in the entire Franklin saga.

By the final week of August the ice around the

Enterprise

and the

Investigator

had loosened sufficiently for the crews to cut a two-mile channel to open water. The long winter ordeal was overâbut not quite. On August 28, after erecting a small house filled with supplies for the sustenance of any members of the Franklin expedition that should find it, the party set sail. Only a few days later however, they were hit by ice flows and carried 250 miles west towards Baffin Bay. Somehow they were able to escape this trap and, by September 25, managed to fight their way into open waters. By this time, almost every member of both ships had become ill. The search was over. It was time to head home.

THE ROSS EXPEDITION

had hardly been a success. They had found absolutely no evidence of Franklin's whereabouts. They had seen no sign of the depot ships that were supposed to have aided them in their search. (Due to miscommunications, Pullen's and Kellett's vessels arrived in the Arctic a year late and did not return until October 1851.) And their voyage back to England was calamitous. Almost immediately, the

Investigator's

cook died from scurvy. A week before England was reached, another crewman passed away. Days after their return, another seaman succumbed in the hospital. In all Ross had lost six of his sixty-man contingent and almost every other member had become alarmingly ill.

Yet Ross had come much closer to finding important evidence than he could have imagined. Although it was within his reach, he had not investigated Beechey Island where, it was later discovered, Franklin had spent his first winter. He knew that, according to his instructions, Sir John was supposed to sail southward through Peel Sound. But when Ross put into Port Leopold for the winter and looked out across the sound he concluded that that would have been impossible. “No vessel could have gone south through Peel Sound,” he wrote in his final report. “All I could see for fifty miles was an unbroken sheet of ice.” Incredibly, the searchers of the passage, and now the searchers

for

the searchers of the passage, had still not learned the basic Arctic tenet that William Scoresby had tried to teach them more than thirty years ago. Despite all his years in the North, James Clark Ross failed to understand that an Arctic channel could be open one year and completely frozen over the next.

CHAPTER 8.

CHAPTER 8.The Prize at Last

“Can it be that so humble a creature as I am will be

permitted to perform what has baffled the talented and

wise for a few hundred years?”

â

ROBERT MCCLURE