Reporting Under Fire (7 page)

Read Reporting Under Fire Online

Authors: Kerrie Logan Hollihan

âIrene Corbally Kuhn

In the summer of 1911, a teenage girl opened a book and wrote her signature on the flyleaf. Under her name and the date, she added an extra flourish as if to say, “I own this book and everything it stands for.”

The Motor Boys in the Clouds, or, A Trip for Fame and Fortune

was new in bookshops, one of a series that took readers on colorful adventures as their characters battled to uphold what was right and just. Just seven years earlier, the Wright Brothers had made the first flight in an airplane, and publishers eagerly printed books for boys, hoping to score profits during those exciting times.

Of course, girls like this book's owner, one Irene A. Corbally of Greenwich Village, New York, enjoyed these stories too. A girl could dream, even if she couldn't look forward to doing everything that boys could. But Irene was determined to live out her dreams, and at 16, she left the path taken by most of the girls who lived in the small homes in Greenwich Village.

The girls and boys had spacious parks in which to play, and in those parks were trees as old as Manhattan Island, trees

under which they sat and held hands on green-painted benches while they “kept company.” Few girls went to business; they graduated from school to helping around the house, learning to be housekeepers themselves for the neighborhood boys they were sure to marry.

Everybody thought I was a strange kind of girl because I turned up my nose at early marriage to a boy I had known all my life. I wanted to write and I wanted to travel.

Like so many Americans in the early 20th century, Corbally lived in a big household with her mother and grandparents and uncles and aunts, but it was her grandfatherâwith her grandmother's inputâwho ruled their Irish-American clan. At 16, Irene announced that she was leaving high school to train as a stenographer, and her grandfather challenged her.

Irene explained that working would allow her to meet people, learn about life, and become a writer. A job as a stenographer could be the first step toward landing a job at a magazine or newspaper. Irene knew enough about herself to realize that she wasn't a writing genius; she would need to practice. She saw herself as one of the “craftsmen who learned to write by putting down one word after another until they could do it with their eyes closed.”

Irene's grandfather granted her wish and sent her to a seven-month stenography school to learn shorthand and typing. She went to work, moving from job to job but always making sure that each one paid a little bit more. As soon as she got work typing letters at

Collier's,

a popular national magazine, she was sure she'd worm her way into a writing job. That didn't happen, and, disappointed, Irene realized that the “ink-stained company I wanted to join were still far beyond my reach.”

Irene went to work as secretary to a Columbia University scientist, who did experiments all day and wrote them up all night. Dr. William J. Gies, professor of biological chemistry, added Irene to his research team studying salvarsan, a German drug that promised to combat the effects of syphilis, the deadly sexually transmitted infection that scourged young American soldiers who were at war in France. Dr. Gies respected his secretary's intelligence, and he taught her how to take measure of herself in both her personal and professional life.

Irene started college classes at Marymount College, but she didn't fit in with girls who were younger and not as worldly. Dr. Gies suggested she enroll at Columbia in its Extension Department, and Irene became an early example of a nontraditional student with a pile of textbooks in contemporary literature, French, logic, philosophy, modern European history, and some writing courses. When she felt ready to look for a job in New York City, the nation's publishing hub, an old-time newspaperman suggested she first get experience upstate.

Irene found a job at the

Syracuse Herald,

which paid $18 per week (less than $250 a week in today's dollars). Working for the paper's city editor, Tom Powers, she quickly proved she had the “nose for news” that marked a successful reporter. Like other women working for newspapers, she was assigned to write feature stories with a “woman's angle.” She yearned for the day when she'd have a byline, usually reserved for hard news stories that appeared on the

Herald's

all-important front page. Her opportunity came when her brief but biting review of a movie caught her editor's fancy, and he gave her a byline. Soon Irene was writing a “short, bright” piece every day as she went around town to discover what people were talking about.

Equipped with upstate experience, Irene moved to the

New York Daily News.

Brainchild of the

Chicago Tribune,

the

News

grabbed readers who shied away from the content-heavy, solemn pages of the

New York Herald Tribune

or the

New York Times.

The

Daily News

was a “picture paper” tabloid called “the stenographer's delight and the gum chewer's dream.” Human-interest stories featuring high adventure, cops and bootleggers, handsome heroes, and fallen womenâthese were the grist of tabloids such as the

Daily News.

If Americans needed newspapers to help them forget the horror of the Great War, then the tabloids were just the ticket.

But Irene, a woman, was forbidden to venture out to report on crime scenes and gangland shootings. Again she was assigned the women's angle, which, in tabloid reporting, meant stories about sex. Readers devoured them. In America's bigger cities, Irene noted,

The war was over. The dead were buried. Most of the living had come home. Come home with a new philosophy gained from intimate acquaintance with trench living on borrowed time. Men had lived with death so long that they seized upon life with a rapist's lust, and life meant women and women meant sex.

Irene, caught up in the excitement of working at an energetic young newspaper, thrived as she wrote stories of scandal and shame. Readers gobbled them up. If Irene's editor, Phil Payne, came under fire for running too many questionable stories, she could argue that he was mirroring contemporary life.

But the

Daily News

wasn't selling enough papers, and Irene, last hired, was first fired. She found a new job as an advertising copywriter for a successful entrepreneur who was doing business in Paris. Her horse-faced, garishly dressed employer, who made millions selling patent medicines and cheap makeup,

turned out to be a glorified snake-oil salesman. When she tried several times to correct glaring errors in ad proofs, she was ordered to be “grammatical someplace else.” It soon dawned on Irene that she'd been hired for less-than-honorable reasons. Sure that she could take care of herself, she set sail for Paris.

From her seat in her Paris office, Irene watched male bosses hire and fire a round of “new pert French faces in the stenographic department to replace those which had been new and pert only a day or two beforeâ¦. Today's favorite was tomorrow's candidate for the guillotine.” One day, when it was clear to her bosses that she wasn't going to bed with them, she was fired.

But Irene had planned ahead. She held an all-important letter of introduction to Floyd Gibbons, who ran the

Chicago Tribune

Paris edition. Reporters worked in a space rented from a French paper, typing their stories on wooden boards nailed onto supports. A board table served as the copy desk, peppered with marks, “scorched reminders of smoldering cigarettes forgotten while tardy genius rang the typewriter bell.”

Again assigned to write for women readers, Irene covered social events, fashion trends, and visits by famous Americans that included a stroll through the park with silent-movie genius Charlie Chaplin, as well as America's sweetheart, movie star Mary Pickford and her new husband, the dashing Douglas Fairbanks. When work hours got long and the

Tribune's

reporters grew thirsty, they lowered an empty pail from their courtyard window to be filled with beer by a café across the way. “We became so expert,” Irene recalled, “we scarcely disturbed the foam. Never did beer taste so good.”

Irene's assignments could turn serious. There was so much suffering in the world. She attended Memorial Day ceremonies outside Paris and gazed across fresh young grass at a field of

white crosses decorated with little American flags. It was her job to check with the American Red Cross each day as it tracked the burials of more than 6,300 dead American soldiers and sent photos of their graves home to their families. When Floyd Gibbons flew into Russia as the first American eyewitness to a hideous famine, Irene's stomach did flip-flops as she translated Gibbons' “graphically ghastly” cable-eseâa style of telegraph shorthand that kept costs in check.

The next December, overtaken with restlessness and angry at her boyfriend, Irene sailed to China with her best pal, Peggy Hull, who had made a name for herself as America's only woman credentialed as a war correspondent. Peggy had been to Asia and was yearning get back. After a weeks-long trip on a Japanese freighter, whose crew assumed that Irene and Peggy were either loose women or spies, Irene arrived in Shanghai minus Peggy but with all of their luggage. During their voyage, Peggy had stumbled upon an old acquaintance, a British officer, and had eloped with him.

Irene had $25 in American Express checks and a letter of introduction that snagged her a job working for the English-language

China News,

whose Mesopotamian (Iraqi) owner had gone legit after successfully dealing in opium, Asia's drug of choice. On her first day at work, she joined her coworkers at a wedding reception, and there she met the love of her life, another

News

reporter named Bert Kuhn. Within weeks, Irene, who had dated many young men over the years, married Bert, left her job, and started to learn the elaborate ritual of home-making in China. They lived in the Bund, Shanghai's sector for Westerners, whose buildings reminded everyone of a German city. Irene looked back on those early days of marriage in a feature article she wrote for the

Los Angeles Times

in 1986, 40 years later:

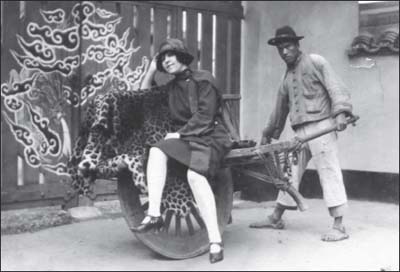

Irene Corbally Kuhn hammed it up for her picture when she lived and worked in China.

Irene Kuhn Papers, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

The standard requirements of a small household of a Westerner then consisted of a No. 1 Boy, a No. 1 Cook (and, if there was to be a lot of entertaining, a Small Cook as well), a Wash Amah, a gardener, a coolie and a jinrikisha ( ⦠rickshaw) coolie, who came complete with his vehicle. That was the minimum. The place of the No. 1 Boy, I soon discovered, corresponded to that of the butler in a large English household. He served as general factotum, ran the rest of the staff and had certain specific additional duties such as serving drinks, waiting table and answering the door. He consulted with “Missy” daily for his marching orders, and he was charged with keeping the household books. At the end of every month there would be a reckoning with “Missy”; she would pay the No. 1 Boy, and he in turn would pay the suppliersâ¦. He

also collected a small slice of the wages of each of the servants under him in the household. There was never any protest or complaint, because it was all part of a complex code. More important, it worked.

In a short time Irene was pregnant, and she and Bert moved to Hawaii so their baby could be born in an American territory. Shanghai was no place to give birthâit was crowded with traffic, noise, and corruption. Even its professional beggars split their takings with a man who operated like some kind of union boss. Everywhere she looked, Irene saw poverty “so profound and so prevalent as to seem beyond rational remedy.” Westerners in Shanghai lived in stark contrast:

Work apartâand we did work hardâsuch was life for the Westerner once privileged to call himself a Shanghailanderâ¦. As I look back down the corridor of years, it was a time apart, a time when it seemed as though nothing had ever been different and thus never would be. In some measure, that state of mind was induced by China itself. Even though the tremors of approaching violent change were occasionally felt, it seemed that the land was too vast, the civilization, the people and their ways too ancient, for change ever to be successful. And yet, even as we lived those days, somewhereâdeep below our consciousnessâwe sensed that this was a life that would never exist again.

In Hawaii Irene went back to work writing for the International News Service (INS). Though it was unusual for a pregnant woman to be working at a jobânot to mention that her husband frowned at the ideaâIrene had tallied the household

budget and saw she needed to get a job. Life moved slowly in Honolulu, and she didn't find her work difficult. Then one morning she called Bert at work, and he passed on a hot tip: the Big Island of Hawaii had been hit by a monster tidal wave.

Such juicy information was too good to pass up, and Irene decided to try to scoop her husband and his competing news service, the Associated Press. Getting the news first would impress her editor on the West Coast. Heavily pregnant, she made her way to the Radio Corporation of America offices where she filed reports. She needed information from the man in charge who held a stack of telegrams coming over the wires. She decided to fake itâacting as if she were going into labor.