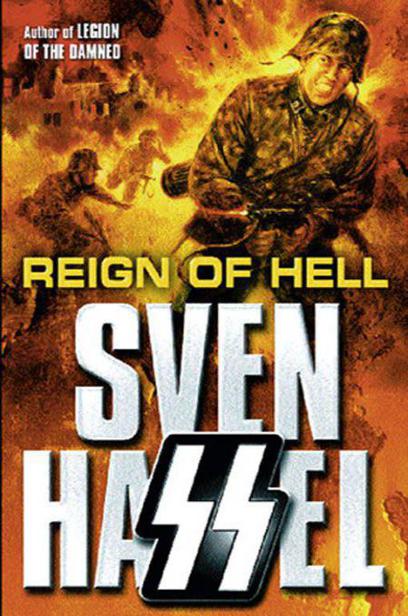

Reign of Hell

Authors: Sven Hassel

The Major from the Pioneer Corps

At the Sign of the Welcoming Goat

A sudden curtain of silence fell over the burning city. All that could be heard was the steady crackling of the flames, and now and then the sound of falling masonry as yet another building collapsed. The Place Wilson, so lately filled with tanks and soldiers, was now deserted. Blackened fragments of paper fell gently to rest on the burnt-out hulk of a tank where the remains of a German soldier sprawled, half in, half out of the turret.

Down in our basement, we crouched in primitive terror as the wall of silence built up round the city. The sound of warfare we could understand, but no sound at all filled us with a nameless dread . . .

By Sven Hassel

Legion of the Damned

Wheels of Terror

Comrades of War

March Battalion

Assignment Gestapo

Monte Cassino

Liquidate Paris

SS General

Reign of Hell

Blitzfreeze

The Bloody Road to Death

Court Martial

OGPU Prison

The Commissar

‘

Why does the Vistula heave and swell, like the breast of a hero Breathing his last on a wild sea shore?

Why does the waves’ lament, from the dark of the deep abyss, Resound like the sigh of a dying man?

‘

From out of the depths of the cold river bed, like a sad dream of death

The song is sung

.

From rain-washed fields the silver willows weep in chorus of sorrow

. . .

The young girls of Poland have forgotten how to smile

.’

‘

The Germans are without any doubt marvellous soldiers

’—

These words were written in his notebook on 21st May 1940

by the future Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke.

This book is dedicated to the Unknown Soldier and to all the victims of the Second World War, in the hope that never again will politicians plunge us into the irresponsible lunacy of mass murder.

‘

What we want is power. And we have it, we shall keep it. No one shall wrest it from us

’—

Speech by Hitler at Munich, 30th November 1932.

None of the men of the 5th Company wanted to become a guard Sennelager. But what does it matter what a soldier may or may not want? A soldier is a machine. A soldier is there for the sole purpose of executing orders. Let him make only one slip and he would very soon find himself transferred to the infamous punishment battalion, number 999, the general rubbish tip for all offenders.

Examples are legion. Take, for instance, the tank commander who refused to obey an order to burn down a village and all its inhabitants: court martial, reduction to the ranks, Germersheim, 999 . . . The sequence was swift and inevitable.

Or there again, take the SS Obersturmführer who stood out against his transfer to the security branch: court martial, reduction to the ranks, Torgau, 999 . . .

All examples have a certain dreary monotony. The pattern, once established, could never be altered, although after a time they did begin swelling the ranks of the punishment battalions by transferring criminals as well as military offenders.

In Section I, Paragraph 1, of the German Army Regulations can be read the following: ‘Military service is a service of honour’ . . .

And in Paragraph 13: ‘Anyone who receives a prison sentence of more than five months shall be deemed no longer fit for military service and shall henceforth be debarred from serving in any of the armed forces of land, sea or air’ . . .

But in Paragraph 36: ‘In exceptional circumstances Paragraph 13 may be disregarded and men serving prison sentences of more than five months may be enlisted in the Army provided they are sent to special disciplinary companies. Certain of the worst classes of offenders shall be drafted into squads occupied solely with mine disposal or burial duties; such squads not to be supplied with firearms. After six months’ satisfactory service, such men may be transferred to 999 Battalion at Sennelager, along with soldiers who have been charged with offences on the field of battle. In time of war, non-commissioned officers must have spent at least twelve months on active service in the front line; in time of peace, ten years. All officers and non-commissioned officers shall be severely reprimanded if found guilty of showing undue leniency towards the men under their command. Any recruit who endures severe discipline without complaint and shows himself fit for military service may be transferred into an ordinary Army regiment and will there be eligible for promotion in the normal way. Before such transfer shall be approved, however, a man must have been recommended for the Cross on at least four occasions following action in the field.’

The number 999 (the three nines, as it was known) was a

joke. Or at any rate, supposed to be joke. It must be admitted that Supreme Command at first totally failed to see the humour of it, for the nine hundreds had always been reserved for the special crack regiments. And then someone kindly explained to them that treble nine was the telephone number of Scotland Yard in London. And what could possibly be more subtle or amusing to the Nazi mind than to give the very same number to a battalion composed entirely of criminals? Supreme Command allowed itself a tight bureaucratic smile and nodded its head in sage approval. Let nine-nine-nine be the number; and just for a bit of further fun, why not preface it with a large V with a red line slashed across it? Signifying: annulled. Cancelled. Wipe out . . . Which could, of course, have referred either to Scotland Yard or the battalion itself. But that was the joke of it. That was what was so excruciatingly funny. Either way, it was enough to make you split your sides laughing. For let’s face it, the swine who served in 999 battalion were scarcely what you could call desirables. Thieves and cut-throats and petty criminals; traitors and cowards and religious maniacs; the lowest scum of the earth and fit only to die.

Those of us sweating our guts out on the front line, didn’t look at it quite like that. We couldn’t afford to. Dukes or dustmen, saints or swindlers, all we cared about was whether a chap would share his last fag with you in times of need. To hell with what a man had done before: it was what he did now, right here and now, that mattered to us. You can’t exist on your own when you’re in the Army. It’s every man for another, and the law of good comradeship takes precedence over all else.

An ancient locomotive grunted slowly up the line, dragging behind it a row of creaking goods wagons.

On the platform, waiting passengers glanced up curiously as the train drew to a halt. In one of the wagons was a party of armed guards, hung about with enough weaponry to wipe out an entire regiment.

We were sitting on one of the departure platforms, playing a game of pontoon with some French and British prisoners of war. Porta and a Scottish sergeant had between them practically cleared the rest of us out, and Tiny and Gregor Martin had for the past hour been gambling on rather dubious credit. The sergeant was already in possession of four of their IOUs.

We were in the middle of a deal when Lieutenant Löwe, our company commander, suddenly broke up the game with one of his crude interruptions.

‘All right, you lads! Come on, look alive, there! Time to get moving!’

Porta flung down his cards in disgust.

‘Bloody marvellous,’ he said, bitterly. ‘Bloody marvellous, ain’t it? No sooner get stuck into a decent game of cards than some stupid sod has to go and start the flaming war up again. It’s enough to make you flaming puke.’

Löwe shot out his arm and pointed a finger at Porta.

‘I’m warning you,’ he said. ‘Any more of your bloody lip and I’ll—’

‘Sir!’ Porta sprang smartly to his feet and saluted. He never could resist having the last word. He’d have talked even the Führer himself to a standstill. ‘Sir,’ he said, earnestly. ‘I’d like you to know that if you find the sound of my voice in any way troublesome I shall be only too happy for the future not to speak unless I am first spoke to.’