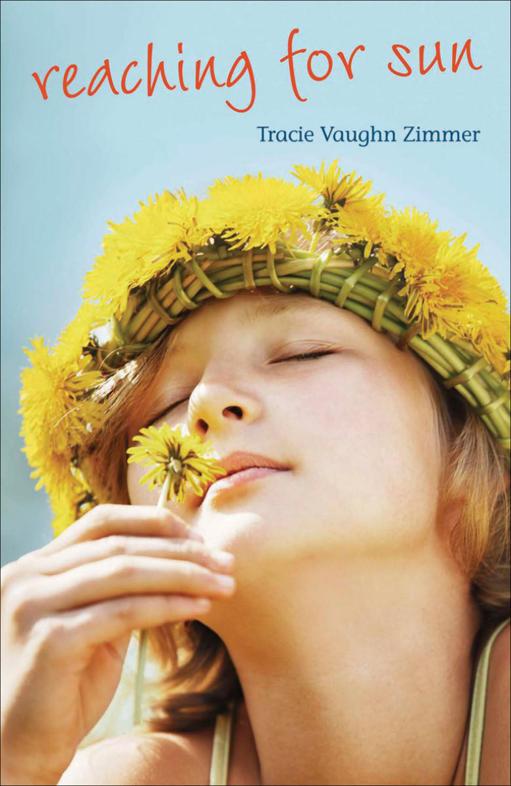

Reaching for Sun (7 page)

Authors: Tracie Vaughn Zimmer

the old screen door

means

Jordan’s home from four weeks at camp.

He’s taller, broader, and tanner,

but when he smiles,

my friend appears.

When I show him

Granny’s sleeping form

on the old chintz daybed

his face collapses,

tears bloom;

he swallows over and again.

I grab his shoulder,

not letting him turn away.

I kiss his cheek,

then hug him.

He smells like soap and syrup.

A long time

we hold on

to each other.

The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop awayfrom you like the leaves of autumn.

—John Muir

On the first day

back to school

Mom and Gran make

Jordan and me

a special breakfast.

Mom flips the pancakes

and sausages at the stove,

while Gran stirs the batter

with her good hand,

though she nearly falls asleep

at the table while we eat them.

On the bus,

Natalie Jackson

walks past our mid-bus seat

without so much as a glance.

“I see the real Natalie is back.”

“Oh, she never left,” he says.

“You remember that day

at her pool? She only wanted me

to fetch the ball for them

when it bounced out.

I didn’t even swim.”

“Then I guess you’re stuck with me, Jordan.”

“That’s just fine with me.”

This fall

Mom works most nights

so she can be with Gran

during the days,

which are measured in

doctor’s appointments

and daily therapies.

Jordan and I

take turns reading to her

by lamplight.

I show her how to use

my loop scissors

with her wrong/right hand

to cut

the pictures out

of her seed catalogs.

We even teach her

Morse code so she can knock

for what she means to say.

But Granny’s sharp words

like cactus needles

have been plucked,

and I miss her

pointed opinions each day.

I never thought

I would ever miss

the sound of

Granny and Mom

exchanging words

like darts.

Now Mom is so

gentle, cautious,

kneeling by her side,

showing her the color

overlays for her first

commercial landscape

design.

The comments

Granny would make

if she could

ping around in my head:

move this here.

This shrub needs a mate.

What fandangled thing is this?

But instead

she just nods,

smiles with half her face.

I bite my lip not to cry,

but Mom lays her head

like a little girl in Gran’s lap

and lets the tears

stain her ancient

mint robe

at last.

Gran’s friend Edna

(the one who stays too long

but brings the best carrot cake

so we suffer her latest complaints,

nodding through mouthfuls),

brought Gran another sick patient.

An African violet

with crown rot—

pitiful swollen stems

that drop if you

breathe too hard on them;

heart-shaped leaves

hanging their heads

like a kid who just got scolded.

It took some time

for her damaged hands to nurse it back,

but finally

double bubblegum-colored blooms

reflect in the frosted window

above the porcelain sink.

I bet a lot of kids

wish for the same thing

as I will this year

with my fourteen candles:

for things to be

just like they were.

I’m lugging homework home—

it feels like

an elephant in my backpack.

Homework should be outlawed

on birthdays—

even ones nobody mentions all day.

I nearly fall through the door

to find

Granny at the kitchen table

pointing

and nodding.

By the look on her face

she might cuss if she could.

Burnt sausage in her iron skillet

and Jordan dusted in flour,

trying to roll out dough.

They both look up—

caught

trying to make my

birthday favorite:

breakfast for dinner,

Granny’s biscuits and gravy

on the red plate!

Out of nowhere

Granny flings her good arm—

a dollop of dough

sticks for just a second to Jordan’s forehead.

She snorts behind her hand.

Then he lobs a glob

of unbaked biscuit at me—

soon the kitchen is covered

in flour,

biscuit balls,

and laughter.

Jordan and I

keep laughing

over Mom’s surprised face

when she walks in on our flour fight

and then joins in.

It’s a day

we both don’t want

to end, standing

near the door on the screened porch,

though neither of us

reaches to open it

first.

On impulse I say,

“Wait here.”

I give him the journal of letters

about my imaginary summer.

I know he’ll understand it.

When I slip it in his hands,

I realize

he’s shot up taller than me

and so fast that later I question

whether it really happened at all—

one quick kiss—

then he nearly falls

rushing out the door.

The wind stinging my face

as I watch his dark figure escaping

into the lavender glow of the night.

What do you want to be?

adults always ask,

as if you know

by fourteen

what you want to be doing

at forty-five.

I used to make up stuff:

firewoman,

pediatrician,

astronaut,

all the people

I knew my mom

wanted to hear.

I know

more what I don’t want to be:

a single parent,

poor,

stuck behind some desk

or in school longer than

I need to go.

And that will have to be

enough

for now.

I decide to finish

the Eiffel Tower mural on the old shed

as a Christmas gift for Gran.

It may take this whole season, but I’ve learned

if I take my time, nothing can stop me.

My fingers sweat inside the rawhide gloves,

the tools for glasswork awkward in my hands.

But I make a little progress each day.

Mom has taken to standing below the stepladder,

shading her eyes with her hand,

talking to my back as I work.

I step down to get a wider view.

“I’m going there someday, you know.”

I say it out of nowhere, but realize I mean it.

“I believe you,” she whispers.

“You do?”

Mom’s cool fingers tilt my chin up at her.

“I believe

in

you, Josie.”

And I press her words

in the pages of my heart

like a first spring bloom.

Shoe to shoe,

leg to leg,

arm to arm,

familiar fingers,

Jordan and I

sway in the hammock

on the autumn breeze.

I convince Jordan we should

join the Young Scientists Club

together

so we can go on their annual trip

to the Smithsonian museums

in the spring.

The pale sky and changing leaves

create a kaleidoscope of color

tumbling and fluttering

around our new plans

and dreams.

It’s the last chance to plant bulbs

for spring,

so I drag a chair

from patch to patch.

Gran shuffles to

her spot and gives me clear

directions with a series

of grunts, nods, gestures.

I understand her wishes

better than my own.

I unroll a length of

yarn

that has laid

dusty far too long

this summer.

Tears puddle in her eyes

and her smile wobbles

as she sees I’ve

spelled her name

with daffodils:

Jocelyn

Even after summer

packs her bags,

the garden blooms:

holly drips berries

for the birds;

the river birch

peels back

to show its pale heart.

A museum opening

of frozen sculpture:

Japanese maple limbs

painted with fresh frost,

ornamental grasses

pause time.

And me,

I’m the wisteria vine

growing up the arbor of this

odd family,

reaching for sun.

This book grew over many seasons with the gener-ous care and insights from many friends: Sue Corbett, Diane M. Davis, Susan Greene, Kim Marcus, Lynne Polvino, Andria Rosenblum, Deb Svenson, Kyra Teis, and support at The Pub. My twin, Trish DeLong, who gossips with me about my characters as if they live down the block, and my mom, who listens to poems over the phone. The divine duo: Jessica Swaim and Julia Durango, who held my hand through every page of every draft. My agent, Barry Goldblatt, for his unwavering faith. Melanie Cecka, who pulled the ribbon of the story from my clenched palm, and the entire Bloomsbury crew for their boundless creativity and enthusiasm. The real Aunt Laura Collier, for ever-lasting friendship. Thanks, always and always, to my husband, Randy, for believing. And for Cole and Abbie, who inspire every word.

Copyright © 2007 by Tracie Vaughn Zimmer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner

whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

First published in the United States of America in March 2007

by Bloomsbury Books for Young Readers

E-book edition published in April 2011

www.bloomsburykids.com

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, Bloomsbury BFYR, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10010

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Zimmer, Tracie Vaughn.

Reaching for sun / by Tracie Vaughn Zimmer. — 1st U.S. ed.

p.cm.

Summary: Josie, who lives with her mother and grandmother and has cerebral palsy,

befriends a boy who moves into one of the rich houses behind her old farmhouse.

ISBN-13: 978-1-59990-037-7 • ISBN-10: 1-59990-037-8 (hardcover)

[1. Cerebral palsy—Fiction. 2. People with disabilities—Fiction. 3. Friendship—Fiction.

4. Grandmothers—Fiction. 5. Single-parent families—Fiction. 6. Novels in verse.]

I. Title.

PZ7.5.Z63Re 2007 [Fic]—dc22 2006013197

ISBN 978-1-59990-812-0 (e-book)