Raisin' Cain: The Wild and Raucous Story of Johnny Winter (Kindle Edition) (22 page)

Read Raisin' Cain: The Wild and Raucous Story of Johnny Winter (Kindle Edition) Online

Authors: Mary Lou Sullivan

BOOK: Raisin' Cain: The Wild and Raucous Story of Johnny Winter (Kindle Edition)

7.89Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

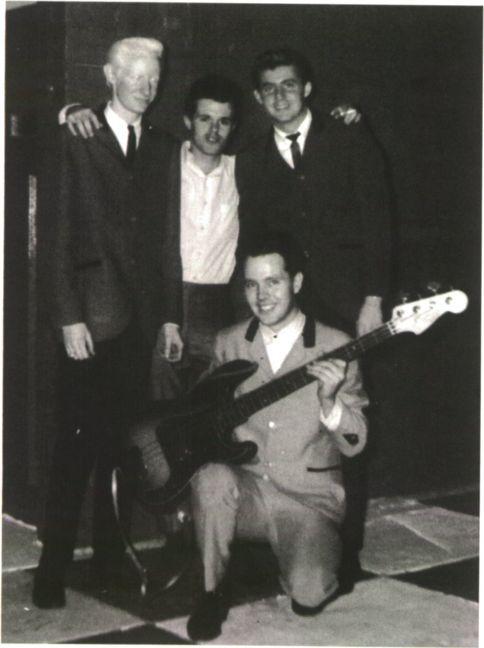

The Gents wore suits with velvet collars before the Beatles. (Photo courtesy of Dennis Drugan)

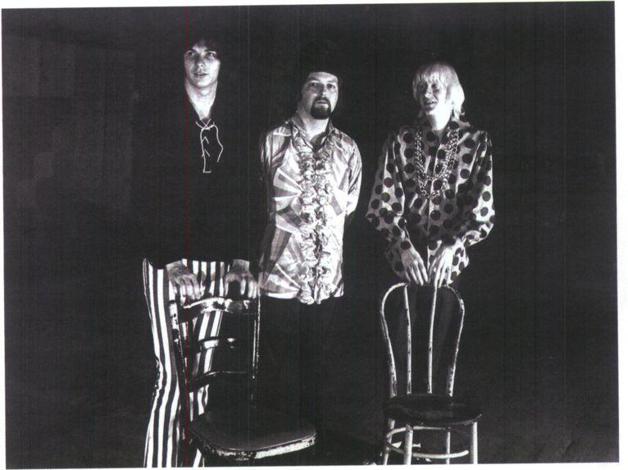

Tommy Shannon, Uncle John Turner, and Johnny in a shot that graced the back cover of

Progressive Blues Experiment.

(Photo by Burton Wilson)

Progressive Blues Experiment.

(Photo by Burton Wilson)

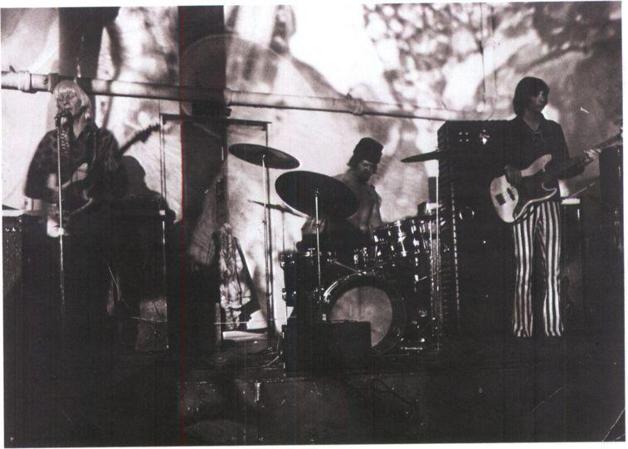

Johnny, Shannon, and Turner with lightshow at the Vulcan Gas Company in 1968. (Photo by Burton Wilson; from the personal collection of Uncle John Turner)

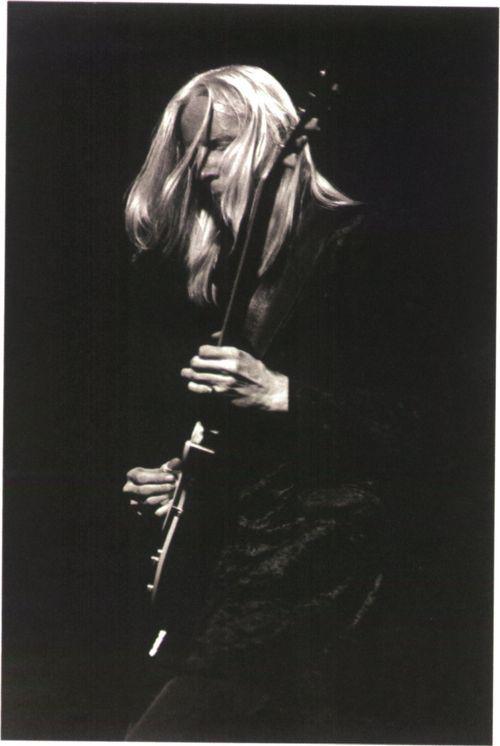

Johnny at Palmer Auditorium in Austin in November 1969. (Photo by Burton Wilson)

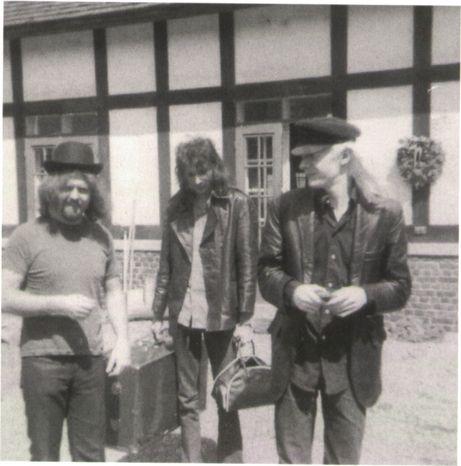

Turner, Shannon, and Johnny at the Staatsburg, New York, house where they lived when they moved to New York. (Photo from the personal collection of Uncle John Turner)

Acetate record Johnny used to shop for a record deal in England in 1968. (Courtesy of Mike Vernon)

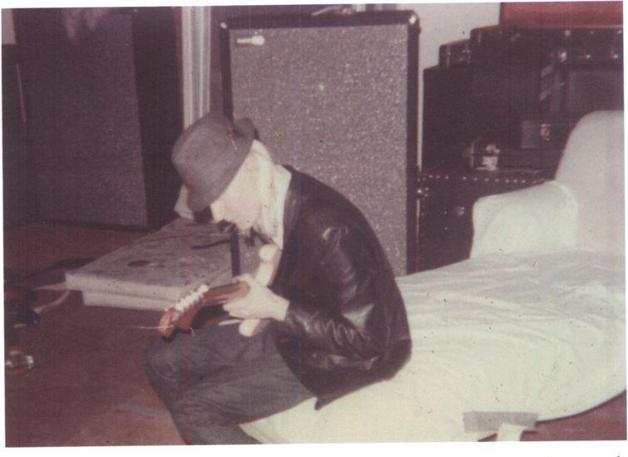

Johnny in the rehearsal space in Staatsburg. (Photo from the personal collection of Uncle John Turner)

Both Johnny and Janis Joplin were featured in ads for Tijuana Smalls in 1969. (Photo by Susan Winter)

“‘You are just business, business; we want to talk art,’” Dali told Paul, in an incident Johnny gleefully shared with his artist friend Jim Franklin. “Steve always wanted to be right in the middle and Johnny was so pleased that Dali put him in his place, which was across the room, where managers should be,” remembered Franklin. But Johnny passed on Daliʹs suggestion that he put a microphone up his derriere so his inner body sounds could also be broadcast when he was performing.

When they weren’t on the road, Johnny and his band lived in a house Paul rented in Staatsburg, New York, a rural town in the Hudson Valley about ninety-five miles from New York City. The house was part of what they called the quadrangle, consisting of two houses and two renovated barns, not far from an estate owned by the Astor family.

“It was an old house on an estate that looked like a compound,” said Turner. “A large brick three-story house with four bedrooms and a brick wall around it. Behind it were two barns. The newer barn was one big room with fourteen-foot ceilings for an artist studio and one bedroom. The other one had two bedrooms and a hayloft. Steve Paul eventually rented the main house too. Originally, it was occupied by a Shriver. He had used it as a getaway for several years and came up on weekends. Our all-night affairs, plus our goings-on in the large heated pool outside between the two houses, ran him off.”

Shannon remembers one bizarre evening when the band dropped acid and headed into the cold winter’s night for a swim in the heated pool. “Johnny decided Steve Paul was literally the devil,” said Shannon. “We did a lot of drugs in Staatsburg—mushrooms, acid, pain pills. All of a sudden, all of that dope was free and we took advantage of it, tried stuff we never tried before. We were pretty high. When you reach a certain point of success, people start giving you drugs all the time.”

It was at the quadrangle that Edgar wrote the riff to a song that eventually became “Frankenstein.” That single reached the top of the

Billboard

charts in only eleven weeks, and boosted sales of Edgar’s 1973 Columbia LP,

They Only Come Out at Night,

to more than 1.2 million copies.

Billboard

charts in only eleven weeks, and boosted sales of Edgar’s 1973 Columbia LP,

They Only Come Out at Night,

to more than 1.2 million copies.

Edgar has fond memories of living in Staatsburg with Johnny and his band. “Living at the quadrangle with Uncle John and Tommy, it really felt like a band, and was very reminiscent of the old days,” said Edgar. “We had a great big rehearsal room in the back of our house. We could make as much noise as we wanted and play any time of the day or night. It was what we had always dreamed of when we were little kids, having our own place and having a band and being able to play music at whatever time we wanted. That was when I originally developed ʹFrankensteinʹ—in that house with that band. We called it the ‘Double Drum Song.’ I played Hammond organ and sax and did a drum solo with Red. I wrote the basic riff specifically with Johnny in mind, thinking of his band, and an instrumental that would have a bluesy feel, and make sense in an instrumental show.”

“We’d start the song with Edgar on the organ,” said Turner. “Then we’d get to a point where the band would stop and I would start doing a short solo in time for Edgar to leave the organ and take a seat at my extra set of drums. As soon as Edgar would get seated, I’d do a special fill, and then Edgar would come in and take it for a little while. We had the tandem drumming thing worked out so we drummed together. Edgar is always a real joy to play with; he is such a great musician.”

Edgar played with Johnny’s band from time to time, and took on a bigger role in Johnny’s second Columbia recording. Johnny returned to the studio in late 1969 to record

Second Winter,

which had a harder rock feel than the straight blues of

Johnny Winter

, and introduced Johnny’s version of “Highway 61 Revisited.” Although pegged as a blues-rock record,

Second Winter

marked the beginning of Johnny’s move toward rock and away from the blues. The inclusion of songs by Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Dylan wasn’t lost on him, and he had serious misgivings about taking that musical direction.

Second Winter,

which had a harder rock feel than the straight blues of

Johnny Winter

, and introduced Johnny’s version of “Highway 61 Revisited.” Although pegged as a blues-rock record,

Second Winter

marked the beginning of Johnny’s move toward rock and away from the blues. The inclusion of songs by Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Dylan wasn’t lost on him, and he had serious misgivings about taking that musical direction.

Other books

The Dance Off by Ally Blake

Emma's Heart (Brides of Theron 3) by Pond, Rebecca, Lorino, Rebecca

Grace Against the Clock (A Manor House Mystery) by Julie Hyzy

Into the Darkest Corner by Elizabeth Haynes

The Falls by Eric Walters

Walleye Junction by Karin Salvalaggio

Long Shot (Watch Out For Joel (myrockandrollbooks)) by SIGMUND BROUWER

Out in Blue by Gilman, Sarah

Resist (Songs of Submission #6) by Reiss, CD

Wolf's Lady (After the Crash Book 6.5) by Maddy Barone