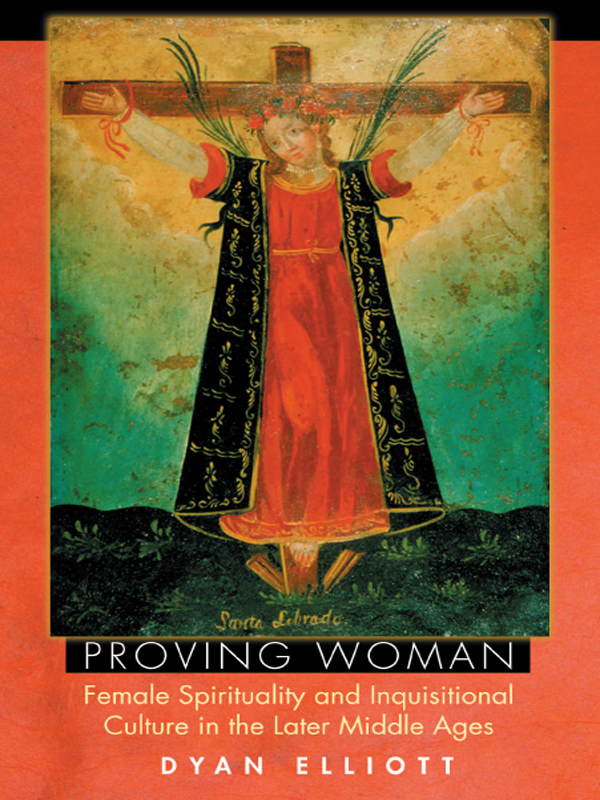

Proving Woman

Authors: Dyan Elliott

Proving Woman

Proving Woman

FEMALE SPIRITUALITY AND INQUISITIONAL CULTURE IN THE LATER MIDDLE AGES

Dyan Elliott

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright ©2004 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Elliott, Dyan, 1954–

Proving woman : female spirituality and inquisitional culture in the later Middle Ages / Dyan Elliott.

p.cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-1-40082-602-5

1. Women—Religious life—History. 2. Church history—Middle Ages, 600–1500.

3. Mysticism—History—Middle Ages, 600–1500. 4. Women mystics—Europe.

5. Heresy—History—To 1500. 6. Inquisition. I. Title.

BR163.E55 2004

270.5'082—dc222003053680

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon

Printed on acid-free paper. ∞

pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 1 0 8 6 4 2

For Gail Vanstone

proven friend, whose friendship has meant so much

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE Sacramental Confession as Proof of Orthodoxy

PART ONE Women as Proof of Orthodoxy

CHAPTER TWO The Beguines: A Sponsored Emergence

CHAPTER THREE Elisabeth of Hungary: Between Men

PART TWO Inquisitions and Proof

CHAPTER FOUR Sanctity, Heresy, and Inquisition

CHAPTER FIVE Between Two Deaths: The Living Mystic

PART THREE The Discernment of Spirits

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MANY DEBTS of gratitude were incurred during the writing of this book. I have been the fortunate beneficiary of considerable

institutional support. At the top of the list is the ongoing generosity and encouragement that I have received from my home

institution, Indiana University, and the Department of History, in particular. I would especially like to thank the chair

of my department, John Bodnar, for his support. I have also been blessed with the opportunity to work in some lovely, even

enchanted, places, for which I am forever grateful. In the academic year of 1996–97, I was the recipient of an ACLS (American

Council of Learned Societies) fellowship while a member of the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study. The following year,

I was a fellow at the National Humanities Center in the Research Triangle, North Carolina. In the spring of 2002, I was the

Visiting Meaker Professor of Medieval Studies at the University of Bristol and then a fellow at the Rockefeller Foundation’s

beautiful Villa Serbelloni in Bellagio, Italy. Many thanks to my fellow residents and colleagues for the stimulation and pleasure

they provided in these remarkable venues. I have particularly benefited from the wisdom, humor, and friendship of Fernando

Cervantes (whom I first met at Princeton and would joyfully reencounter at the University of Bristol); Peter Jelavich and

Judy Klein (from the National Humanities Center); and Carolyn Muessig and Elizabeth Archibald (University of Bristol). I would

also like to thank the wonderful members of my postgraduate seminar in Bristol on gender and popular religion, who taught

me all about learned pub nights—a sadly neglected discipline in North America.

Thanks to Peter Jelavich, who helped me with some German translations and stoically read and commented on the entire manuscript;

to Paul Strohm, who read and commented on several chapters; and to the anonymous readers of Princeton University Press, who

I have since learned to my own (and the manuscript’s) good fortune were Penelope Johnson and Barbara Newman. I am additionally

appreciative for the support of my editor, Brigitta van Rheinberg, and of Lauren Lepow—manuscript editor extraordinaire! Working

with Brigitta was a new pleasure. But I had worked with Lauren earlier with such happy results that I would spend months scheming

over how I could ensure being assigned to her again. As before, the experience has been deeply gratifying.

Chapter 4 incorporates sections of my articles “

Dominae

or

Dominatae

? Female Mystics and the Trauma of Textuality” (in

Women, Marriage,

and Family in Medieval Christendom: Essays in Memory of

Michael M. Sheehan, C.S.B.

, ed. Constance Rousseau and Joel Rosenthal [Kalamazoo, Mich.: Medieval Institute Publications, 1998], pp. 47–77); “The Physiology

of Rapture and Female Spirituality” (in

Medieval Theology

and the Natural Body

, ed. Peter Biller and Alastair Minnis [Wood-bridge, Suffolk: York Medieval Press in association with Boydell and Brewer,

1997], pp. 141–73); and“Women and Confession: From Empowerment to Pathology” (in

Gendering the Master Narrative: Women and

Power in the Middle Ages

, ed. Mary Erler and Maryanne Kowaleski [Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2003], pp. 31–51). The lion’s share of chapter

7 is a condensed version of “Seeing Double: John Gerson, the Discernment of Spirits, and Joan of Arc” (

American Historical Review

107 [2002]: 26–54). I would like to thank the respective presses for the right to make use of this material.

I cannot imagine writing this book without the unstinting and loving support of certain other friends, who were always there

during the trying times when my focus mysteriously shifted from

Proving Woman

to “Proving Dyan.” David Brakke, Dori Elliott, Mary Favret, Susan Gubar, Don Gray, Wendy Harris, Pat Phillips, Carol Ribner,

and Mary Jo Weaver all deserve my heartfelt thanks. But I particularly wish to acknowledge my enduring indebtedness to Gail

Vanstone, to whom this book is dedicated.

Proving Woman

Introduction

THIS BOOK addresses the trajectory of female spirituality over the course of the High and later Middle Ages. From a certain

perspective, it is a familiar story to which all students of the medieval and early modern periods can supply the ending:

during this period, female spirituality (“always already” suspect) is progressively perceived as a substantial threat to the

church and society at large. This gradual criminalization of female spirituality parallels the progressive efforts to constrain

and even persecute women, an impetus most dramatically illustrated in the witch-hunts of the early modern period. Therefore

this book is not really about what happens to female spirituality, but about why it happens. It attempts to isolate a constellation

of factors that help to explain this process.

At the very center of this problem are the various convulsions medieval society was undergoing around the time of the Fourth

Lateran Council (1215). As papal antidote to contemporary confusion, Lateran IV is undoubtedly the clearest statement we have

of the problems confronting the medieval church in this period as viewed through the lens of the higher clergy. Although the

problems are legion, there are several strands that are of particular importance to this study: the threat of heresy; the

regulation of sanctity; the new emphasis on the sacraments, particularly confession and the eucharist; and the introduction

of the inquisitional procedure. From the perspective of the church hierarchy’s disciplinary measures, these three strands

are strategically interwoven in the fight against heresy: heretical antisacramentalism is countered by a due reverence for

the sacraments, which becomes one of the benchmarks of orthodoxy; saints are newly perceived as key players in the struggle

against heresy—hence an emphasis on the sacraments becomes intrinsic to con-temporary profiles of sanctity; the inquisitional

procedure will soon be adopted as the instrument for assessing both sanctity and heresy; and the sacrament of confession,

made mandatory for the first time at the council, emerges as a new proof of orthodoxy, obliquely corresponding to the emphasis

placed on confession in inquisitional procedure. All of these considerations are implicated in the way in which female spirituality

is portrayed in this period.

Lateran IV also both signals and abets a more abstract change that affected individuals in all walks of life: a growing concern

with what constitutes proof. The outlawing of the ordeal and the introduction of the inquisitional process are certainly the

most explicit conciliar articulations of this change, but the deliberations of the council are everywhere riddled with similar

problems of evidence. Undoubtedly the most pressing of these issues is what constitutes orthodoxy or heresy. Papal efforts

to control the identification of saints or the public veneration of relics are like-wise freighted with considerations of

proving authenticity. Many of these proof-fraught questions remain unanswered, but others would eventually find resolution

through recourse to the inquisitional process, a disciplinary measure promoted by this council in response to the problem

of how to proceed against a cleric accused of a crime. Very soon, a wide set of ecclesiastical and secular tribunals will

look increasingly to the inquisition as the primary mechanism for the production of truth. Therefore through-out this study,

the term “inquisition” (

inquisitio

), even when applied to a particular tribunal, should be understood in the widest sense as a procedure not limited to one

forum but the province of many. In all cases, the term is more reflective of a process than of an institution—a point that

needs constant reiterating particularly with respect to heresy.

1

Contemporary representations of female sanctity were in many ways sculpted to confound the heretic. Central features of women’s

spirituality that first emerged during this period—its physicality, eucharistic devotion, confessional practice—all answer

to this need, providing vivid proof of orthodox contentions. This study examines what the phenomenon of women as proof of

orthodoxy means: how female spiritual claims were first established, subsequently wielded, and then ultimately discredited.

Both the supporters and the detractors of holy women looked progressively to more or less formal versions of the inquisitional

procedure in order to prove (or disprove) the authenticity of women’s spiritual lives. One of my arguments is that the continued

application of this procedure progressively undermined clerical perceptions of the essential integrity of female spirituality,

whatever the original motive dictating the adoption of this procedure. Ultimately, the procedure itself contributes substantially

to the faltering profile of female spirituality to the extent that, by the end of the fourteenth century, women will no longer

be perceived primarily as proving orthodoxy’s dogmatic contentions—contentions that have, by now, been satisfactorily sustained

in any event. Instead, women’s faith and religious practices will be increasingly scrutinized from a skeptical standpoint,

and the women themselves will ultimately be required to prove their own orthodoxy. Moreover, female sanctity is not a discrete

phenomenon, cordoned off from its larger spiritual setting. The common application of the inquisitional process for the purpose

of establishing the veracity of both sanctity and heresy tended to narrow the gap between these two conditions generally.

The holy woman’s downward spiraling can again be perceived as both symptom of and stimulant for this gradual dissolution of

coherent categories. But like Lucifer, she did not fall alone. Even as the rebellious angel took a good chunk of the heavenly

host along with him, the female saint also dragged positive representations of sanctity along in her wake.

Thus far I have been using the word “proof” in a legalistic or academic sense: to prove a case; to prove a position—both of

which activities are accommodated by the Latin verb

probare

. But the same word had other dimensions as well. God proves his saints as gold in the fire, which in this context would be

best understood in the sense of “tests” or “tempts.” This manner of proving functions as a way of manifesting both to God

(whose omniscience does not really require this information) and especially to humankind that the person in question is, indeed,

a saint. Such testing, however, was not restricted to the perfected individual; it could also serve a purgative function for

the sinner. Thus God proves the sinner through the infliction of suffering to purge an individual of sins for his or her own

good. The expiational effect of purgatorial fire is but one aspect of this sometimes bewildering side of divine clemency.

Although the agents for inflicting such persecution had traditionally been associated with the devil, the celebration of suffering

in the High Middle Ages will interfere with the devil’s near monopoly over the administration of such travails. The rising

appreciation of the value of suffering alters the traditional perception of the agents responsible for its infliction, tending

to purify, justify, and sometimes even sanctify the punitive function of both church and state. We hear an echo of this process

in Chaucer’s hagiographically inflected

Clerk’s Tale

and its justification of the coercive aspects of gender roles dictated by the institution of marriage. The virtuous wife,

Griselda, who is likened both to Job and to gold in the fire, demonstrates her submission to God’s will through submission

to her husband’s authority—even when such submission requires the sacrifice of her children. The concept of proving is possessed

of still darker aspects:

probare

is also a verb used for torture—a possibility that is at the center of the martyr’s

passio

but that invariably hovers at the edge of the heretical trial. In other words, I am seeking to encounter proof in its many

different guises, and the ways in which these meanings reverberate in the religious lives of medieval women and society at

large.

This study arose out of the sense that the categories of saint and heretic have too often been treated in isolation, or at

least oppositionally—a dualistic perspective that in many ways reflects ecclesiastical hopes. There are some studies that

represent exceptions to this kind of compartmentalization: scholars such as Peter Dinzelbacher, Richard Kieckhefer, and Aviad

Kleinberg have all pointed to a number of disputed cases of sanctity, or circumstances under which the distinction between

saint and heretic breaks down altogether.

2

Similarly, Barbara Newman has treated orthodox and heretical mystical writings as indivisible aspects of a coherent corpus.

3

The present work likewise seeks to challenge the boundaries be-tween sanctity and heresy: first, by analyzing their symbiotic

natures, and second, by examining procedure with a view to understanding unintended effects. As suggested earlier, the very

mechanisms developed for discerning the saint and the heretic inevitably make these categories more proximate. In order to

trace this progressive development, I have cast my net as widely as possible, enlisting sources that reflect each of these

imagined polarities: hagiographies, processes of canonization, heretical trials, manuals for both confessors and inquisitors

of heresy, theological and canonical writings, ritual protocol, chronicles, and exempla are among the sources consulted to

shed light on how the purity of an individual’s spiritual metal is tested or “proved.”

The sacrament of confession is at the very heart of representations of female spirituality in this period, and the far-reaching

implications of this emphasis constitute one of the major themes of this book. Thus chapter 1 examines the concurrent rise

of sacramental confession and its inquisitional counterpart with a view to illuminating how this parallel fostered what I

refer to as a “covert bridge” between the respective tribunals. The two chapters comprised by part 1 focus on the way in which

the female spirituality emerging in the wake of Lateran IV was shaped within the confessional relationship and then deployed

in the fight against heresy. Chapter 2 analyzes the antiheretical impetus of the Beguines’ confessional practices: their profound

veneration for their confessors, their scrupulosity, their visions of purgatory, and their extreme asceticism. Taken together,

these features function as a profound endorsement not only of auricular confession but of the entire penitential framework

on which the sacrament depends. The example of Elisabeth of Hungary, the focus of chapter 3, reveals a different aspect of

the church’s antiheretical initiative. Both during her lifetime and after her death, Elisabeth was in the hands of the chief

architects of the inquisition against heresy: Gregory IX; his penitentiary, the canon lawyer Raymond of Peñafort; and especially

her confessor, Conrad of Marburg, who happened to be the first papal inquisitor. As with the Beguine movement, Elisabeth’s

unquestioning obedience to her confessor becomes an exemplar used to combat heresy. But the methods employed by her confessor

are an early symptom of the heretical tribunal’s possible infestation of its sacramental counterpart.

Part 2 explores various deployments of inquisitional procedure with a view to understanding how it impinges on the assessment

of an individual’s spiritual profile. The fourth chapter begins with a detailed examination of the protocol followed in two

kinds of papal inquisitions: the process against heretics and the canonization of saints. The use of the

inquisitio

in both instances enhances the permeability between for a alluded to above. But the application of this procedure also demonstrates

the limitations of clerical control: the chapter concludes with instances from heretical trials or failed canonizations that

demonstrate the

inquisitio

’s potential for reversal and other unintended consequences. The fifth chapter concerns individuals who are regarded as holy

during their life-time and the ways in which their claims to sanctity are proved, largely by somatic evidence. Such proof

can, however, be falsified, as a number of instances of imposture clearly demonstrate. The chapter concludes with the rising

tide of medical discourse and its tendency to pathologize, and thus discredit, the most celebrated features of female spirituality.

Part 3 addresses the rise of the discourse of spiritual discernment in the schools. Clerical culture is the focus of chapter

6. By beginning with a demonstration of the parallels between the scholastic methodology and the inquisitional process, and

the inherent reversibility of the verdicts arrived at by each, the chapter points to the ultimate instability of any given

position. It then turns to certain Ockhamite-inflected questions raised in university circles, which have the effect of casting

doubt on mystical experiences. Such clerical apprehension is a contributing factor to the rise of the discourse of spiritual

discernment, which, in response to the rise of some highly visible contemporary prophets and visionaries, was intended to

assess the validity of their experiences. Chapter 7 examines how theologian and chancellor of the University of Paris John

Gerson deployed the discourse of spiritual discernment in order to discredit female mystics—an endeavor associated with his

larger strategy of appropriating mysticism to reform the university. His subsequent failed attempt to defend Joan of Arc will

ironically testify to the success of his antiwoman initiatives. Gerson’s efforts were enthusiastically embraced and extended

by subsequent scholars, hence placing a seal on the declining fortunes of female spirituality. Ultimately, the distance between

saint and heretic practically disappeared. The church had always been prepared for this eventuality. Christ himself had long

ago cautioned against the false Christs and false prophets that would arise toward the end of time (Matt. 24.23–24). The later

Middle Ages believed, perhaps with good reason, that this dire time was finally at hand.

There are certain tendencies implicit in this study that may, I fear, exasperate individual readers. First, I am concerned

with how the religious identity of an individual is established—be that person a saint, a heretic, or just an undifferentiated

member of the faithful. This orientation periodically requires a close examination of what might be considered aspects of

the clerical culture of work: confessors’ manuals, ecclesiastical procedure, ritual, scholarly convention, and theological

controversy—masculine discourses, sometimes peppered by case studies that, if they address questions of gender at all, usually

do so only obliquely. But these various facets are essential to an understanding of the environment in which female spirituality

develops, is apprehended, and is assessed. A reader may further experience frustration with my approach to the women discussed,

contending that I never really touch base with their spiritual lives. From this perspective, the presence of “female spirituality”

in the title of this study may be perceived as highly misleading. In a certain sense, I would have to agree: this study both

is and is not a book about female spirituality. It

is

insofar as it isolates factors that played an important role in how female spirituality was presented and how these representations

were used. Moreover, it points to the propitious conditions under which female spirituality first flourished as well as the

prohibitive ones that sought (often unsuccessfully) its suppression. But this study is

not

about female spirituality in terms of analyzing what the women in question really believed or experienced, even if, occasionally,

such questions are addressed. In short, I am seeking to examine an important component of what might be described as the “frame”

for female spirituality; I am not nearly as concerned with the picture within that frame except from the rarefied perspective

of why the picture assumed the appearance it did, and how certain parties within the clergy may have sought to capitalize

on it.