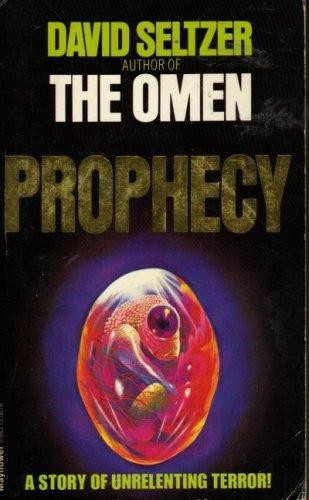

Prophecy

Authors: David Seltzer

In the boreal forests, untouched since time began …

Maggie joined her husband Rob on a research mission into the wilderness of northern Maine. Instead of finding a land of beauty and peace, they found themselves caught in a nightmare-one that Maggie knew would never end.

PROPHECY

ii

David Seltzer

BALLANTINE BOOKS NEW YORK

iii Copyright Š1979 by Paramount Pictures Corporation

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Ballantine Books of Canada, Ltd., Toronto, Canada.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 78-74246

ISBN 0-345-28034-2

Manufactured in the United States of America

iv

To Hector M’tal

v

1

1

Snow fell upon the Manatee Forest, ushering in the awesome silence of winter. It fell for five days and nights, burying the trees that provided work for the lumberjacks, icing the river that provided food for the Indians. The men of the forest retreated, huddling for warmth within the confines of small shelters, subsisting on meager supplies, until the coming of spring.

The other creatures of the forest were better prepared. Through millions of years of evolution they had adjusted, with body structure and bio-rhythm, to the famine and cold that lay ahead. The insects ensured the safety of future progeny by depositing their eggs beneath the water and below the frostline, where they would be impervious to the elements above. The birds would migrate to warmer climes; the coldblooded reptiles and amphibians would assume the same body temperature as the environment, freezing solid, then thawing to life with the coming of spring. The few warm-blooded creatures who could survive on the meager vegetation buried beneath the snow would remain awake through the winter, their bodies and numbers thinning as they foraged the bleak terrain. Those that demanded a greater supply of food would hibernate, falling into a deathlike coma with heartbeats and respiration that could barely be perceived.

Hidden beneath the white blanket that blurred the border between Canada and Maine, tens of thousands of animals lay slumbering in the darkened

2

silence of their dens. Some would emerge with new offspring that had been born while they slept; others would not emerge at all, expiring quietly from old age or starvation, permanently sealed in their earthen tombs. Concealed from the eyes of man, these secret pockets that held life in suspended animation were used over and over through the years, some of them dating back centuries in time. They ranged in size from the teacup-shaped nest of the chipmunk to the ten-foot-wide cavern of the bear.

But this year there was a new hibernation den. And it had a size and configuration unlike any ever built before. Nestled within craggy cliffs at the edge of a frozen lake, it loomed almost thirty feet high and twenty feet wide, and the air within it was thick with the strench of rotting carcasses. The tenant’s sleep had been restless. It was eager for the coming of spring.

As the sun moved closer to the earth, the snow that covered the Manatee Forest began to thaw, stimulating the forest’s creatures into wakefulness. From its subterranean sanctum dug in the mountains above the tree line, a seven-hundred-pound black bear awakened early and stalked in search of prey. The ground was still covered with a thin white crust, creating a trail of paw prints behind him as he descended to the lake, broke the ice with his massive paw, and drank his fill of water. Satiated, he surveyed the environment, detecting the sound of bark being torn from the base of a tree. Following the sound, he spotted a massive buck feeding in the distance, its stately antlers turning as it sensed that danger was near.

The bear moved slowly, knowing that the deer could not escape him; the deer seemed to know it, too, its posture sagging with resignation as it watched the lumbering specter of death approach. At the last moment the deer spun and the bear charged; the pursuit was silent, save for the muffled impact of paws and hooves upon the snow and the grunt of exerted breath as the bear quickly overtook its prey. With a

2

single swipe the bear’s claws ripped into a rear leg and the deer went down, blood seeping into the snow as it struggled, then stopped, watching the bear move in for the kill.

It would not be a swift death. The bear did not have to hurry. There was nothing in this forest that could steal its meal away.

But as it ambled forward, it heard a sound from directly behind. It was an abrupt squeal, a voice unlike any the bear had ever heard. A shadow suddenly loomed overhead, and the bear spun, squalling like a frightened fieldmouse. It tried to run but was jerked upward with such force that its body ripped from its hide, the skinless torso taking flight and slamming hard onto the ground. The legs continued to pump, running in place, even after the head had been neatly sliced from the shoulders.

The wounded deer staggered to its feet, dragging limp hindquarters, finding safety in a thick stand of trees. There it turned and watched with dispassionate eyes the sight of its predator being turned into prey.

The head of the bear was devoured on the spot, the body carried back to the den among the cliffs. There it would be eaten at leisure, its bones thrown onto the pile of carcasses that would grow higher throughout the spring, creating a macabre scaffolding that would reach to the top of the thirty-foot walls. The architect of this cavern had no taste for hooves and claws; they had been severed and left rotting on the earthen floor.

Before long, hands and feet would lie rotting there, too …

3

4

4

5

5

1

To Robert Vern, the coming of spring in Washington, D.C., meant more than cherry blossoms and the start of punting season on the Potomac. His own experiential calendar marked the change of season with a shift in the nature of human misery. Winter was the time of gas leaks, child battering, pneumonia, and asphyxiation; spring was the brief overture to the rat bites and sewage problems of summer.

In his four years of working for the Department of Public Health, he had seen the tenements go from bad to worse. And he was swept with a sense of personal failure. He was a doctor. His patient was the entire ghetto. And its heartbeat was failing, despite his efforts.

In the complicated tangle of cause and effects, a change in national mores was having a dramatic effect on urban development. The young middle-class working corps, who had once paired up, gotten married, and lived in suburbs where they could send their children to “good” schools, were staying single now, invading the heart of the city and creating a land boom on which every owner of real estate was prospering. Areas once designated for public housing were being rezoned, and the ghettos were getting squeezed. In a single one-block tenement area where two thousand blacks once lived, there were now six thousand. Families of eight were inhabiting single rooms, spilling out onto the fire escapes, and sidewalks, so desperate for

6

housing that they were at the complete mercy of the slumlords. If they complained that there was no water, they would be thrown out into the streets.

If there was one single group of people whom Robert Vern felt vengeance toward, it was slumlords. On bis never-ending rounds of the tenements he saw the mark of their greed everywhere. He filed lawsuits against them and faced them down in court; ultimately, even if they were penalized, they always won. They owned the real estate and it was in short supply. The tenants knew better than to appear in court and be identified.

Then there were the politicians. The endless stream of sunlamp-tanned bureaucrats who showed up to have their pictures taken at the openings of housing projects, then became unavailable to assist when the projects lost their funding and turned into crime-ridden ghettos. There seemed to be no solution for it, and no end. No one, except Robert Vern, seemed to care.

To the community of people among whom he worked, Vern was an irritant, an idealist who refused to grow up. He even looked younger than his years; his six-foot frame and boyishly handsome face would have been more credible carrying a football on a college campus than a doctor’s bag in Washington. The age of youthful enthusiasm was gone from the capital, dead with Kennedy and the Peace Corps; but Robert Vern was still imprisoned within that time capsule, fired with the belief that the sheer energy of one man who knew right from wrong might ultimately prevail. His social conversation was diatribe, his zeal frightening. Few dared to befriend him for fear of getting caught up in his combat with the world.

And yet, in his dealings with the impoverished and disinherited, he was a man of consummate gentleness. He literally ached for them, sometimes even felt guilty for having been born with all the possibilities in life that they would never have.

He had spoken to a psychiatrist once, at a fund-

7

raiser for community mental health services, and after a lengthy conversation the psychiatrist had suggested that Rob go into therapy. He observed that Rob suffered from what he called a “Savior Syndrome,” a neurosis that makes one behave in a God-like manner to compensate for some kind of guilt or for the lack of a simple feeling of human self-worth. Such people, the psychiatrist went on to explain, can feel worthwhile only when they associate with the weak and helpless. Those who need them.

The superficial analysis had irritated Rob, but he knew that it touched upon a basic truth. There was plainly a disparity between what he was trying to accomplish, and what he could accomplish. It made him fear that he was acting more out of his own needs than those of others. At the age of thirty-nine he was at a crossroads, his mind given to analyzing not only where he was going, but where he had been.

He remembered that even as a young boy he had had a desire to heal. When he bought tropical fish for his aquarium he always passed over the healthy ones, choosing instead those that were covered with white spots or limped through the water with battered fins. He toiled over them day and night, curing icthiomy-atosis and dropsy with the same kind of dedication he had witnessed in his own father, a country doctor, who had died when Rob was twelve.

He had gone to college on scholarship, then on to medical school. After graduating with honors, he spurned the rewards of private practice to minister to the needs of those who could afford no medical treatment at all. He went to Brazil with the Peace Corps, where he became expert in the diseases borne of environmental squalor; then, two years later, to New York, where that field of expertise became his specialty. He worked at Bellevue Hospital, an institution that is to the medical profession what the Ford Motor Company is to automobile production. An assembly line, through which patients move so fast and continuously that they all begin to look alike and the

8

doctors themselves lose their sense of identity. Rob worked a twenty-hour day, and it was there, on a night when he was feeling lost and alone, that he met a young woman named Maggie.

Maggie Duffy, now Maggie Vern, Rob’s wife of seven years, was at that time a student at the Juilliard School of Music. She had brought her cello and two friends with violins into the Children’s Ward, to serenade on Christmas Eve.

After all these years, it was still Rob’s fondest memory of her. She was playing Brahms, her cheeks wet with tears from the sight of the children; she used a Kleenex, which she kept tucked under the cello strings at the very top of the instrument near the tuning knobs, to dry her tears between selections. When she played, it was as though she were completely at peace; a single entity expressing a single feeling. That feeling was compassion.

They spent that night together, walking the cold, deserted streets of Times Square, feeling, in the uncommon emptiness of Christmas Eve, as though they were the earth’s only two survivors. With a sense of urgency, as though they might never cross each other’s paths again, each told the other the entire story of their lives. And by dawn of Christmas morning, over coffee and cherry pie at the Automat, each secretly knew that they had found their life’s partner.

It was Maggie’s optimism that Rob most admired; her naivete, her openness, her vulnerability. In many ways she was like an innocent child; easily hurt, quickly consoled, exuberant one moment, pensive the next-responding immediately and instinctively to everything around her. Whereas Rob dwelt in the province of the mind, she followed the dictates of her feelings. Together they were a perfect combination.

Their first apartment in New York was just off Columbus Circle; Rob used to watch Maggie through the kitchen window, dragging her cello behind her as she walked to her morning class at Juilliard. She often took a glass of water with her to nourish a small